Share On Social!

This is part of our Healthier Schools & Latino Kids: A Research Review »

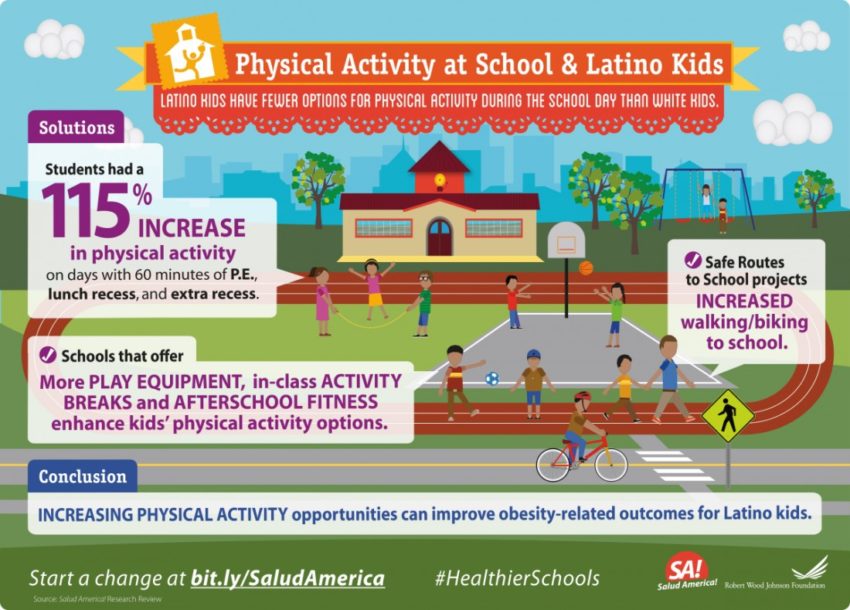

Latino students have few options for physical activity during school

Studies suggest that Latino children may have fewer opportunities to engage in physical activity at school than their White counterparts.

In a study evaluating physical education and recess practices among U.S. public elementary schools,44 elementary schools with primarily Latino students were less likely than those with primarily White students to offer 20 minutes of recess daily.

Latino schools were also less likely than White schools to offer physical education for at least 150 minutes per week, although the difference did not reach statistical significance.

A study of 102 public elementary schools in Rhode Island revealed that schools with high minority enrollment (≥10% African American, ≥25% Latino, or both) offered fewer programs supporting healthy eating and physical activity than schools with low minority enrollment.45

Schools with high minority enrollment were less likely to offer physical activity (P < .05), and children at those schools were less likely to participate in 20 minutes or more of recess play per day (P < .001).

Additionally, children in high-minority schools had less access to physical activity facilities, such as playing fields and tracks. No differences were found in access to physical education between low- and high-minority schools.

Schools can make efforts to increase physical activity

One study of majority Latino and majority overweight elementary school students in the southwest United States found that, after four days of unstructured recess and four days of semistructured recess, children overall had more minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) during semistructured exercise, and both boys and girls had significant increases in activity time during semistructured exercise.

The authors also noted that the children did not have a statistically significant preference between semistructured recess, in which children chose either jumping rope, walking, soccer, basketball, or tag games, and unstructured recess.46

A study of 298 fifth grade children (39% Latino, 17% overweight, and 23%obese) evaluated the number of steps and amount of moderate to vigorous physical activity the students were able to achieve using four different physical activity models.

The first model was a single 20 minute lunchtime recess; the second model was a 20 minute lunch recess with the addition of a second 15 minute recess; the third model was a 30 minute PE class with a 20 minute lunchtime recess; and the fourth model was a 30 minute PE class, a 20 minute lunch recess, and an extra 10 minute recess.

As expected, the children logged the most steps and the highest amount of MVPA using model 4; compared to days with only one PA opportunity, children had a 58% increase in steps and a 115% increase in MVPA on days with three activities.47

Schools struggle to achieve policies to boost activity

Even when states have policies for increasing physical activity, schools are often challenged to implement them due to competing priorities, lack of resources, insufficient knowledge about the policy among school administrators, and insufficient enforcement of policy.48

Additionally, staff perceptions about the role and responsibility of schools in providing opportunities for physical activity may present challenges. A small study of Latino parents of first-graders and school staff found that staff members often believed that parents—not the school—had the greatest responsibility in ensuring that children were physically active.49

In a survey of California students grades 1-12 (43% Latino), 66.7% of students in grades 1-6 reported having less than 200 minutes of in-school physical activity over 10 school days; of those students in grades 1-6 who had scheduled PE three times per week, 55% still reported less than the required 200 minutes/10 school days.

Of the students in grades 7-12, 42.2% reported having less than 400 minutes of physical activity over 10 school days.

Results of this survey suggest that twice weekly physical activity is not sufficient for most students to meet the recommended 200 minutes/10 days for grades 1-6 and 400 minutes/10 days for grades 7-12.50

In a study evaluating the interim progress of 224 low-income and predominantly African American and Latino schools receiving technical training assistance from the Healthy Schools Program, Beam et al found that, overall, the training assistance improved the schools’ policies and practices regarding obesity prevention.

The goal of the Healthy Schools Program, a national school-based obesity prevention program, is to assist schools in implementing nutrition and physical activity policies.

The results of the interim progress evaluation showed improvements to school meals and school employee wellness; improvements in physical activity, however, were lacking.

This study helped identify the Healthy Schools Program technical training assistance as a valuable tool for assisting schools in the implementation of wellness policies in accordance with the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010, and also identified areas that may require more effort.51

Educating school staff members about their role in providing physical activity, providing staff with sufficient support to allow time for physical activity (i.e., in-class activity breaks)52, and implementing consistent school policies and programs targeted at increasing physical activity may help to prevent childhood obesity.

More from our Healthier Schools & Latino Kids: A Research Review »

- Introduction & Methods

- Key Research Finding: School food environment

- Key Research Finding: School food policies

- Key Research Finding: Physical activity (this section)

- Key Research Finding: Access to activity programs

- Policy Implications

- Future Research Needs

References for this section »

(44) Slater, S. J.; Nicholson, L.; Chriqui, J.; Turner, L.; Chaloupka, F. The Impact of State Laws and District Policies on Physical Education and Recess Practices in a Nationally Representative Sample of US Public Elementary Schools. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2012, 166 (4), 311–316.

(45) Pearlman, D. N.; Dowling, E.; Bayuk, C.; Cullinen, K.; Thacher, A. K. From Concept to Practice: Using the School Health Index to Create Healthy School Environments in Rhode Island Elementary Schools. Prev Chronic Dis 2005, 2 Spec no, A09.

(46) Larson, J. N.; Brusseau, T. A.; Chase, B.; Heinemann, A.; Hannon, J. C. Youth Physical Activity and Enjoyment during Semi-Structured versus Unstructured School Recess. Open J. Prev. Med. 2014, 2014 (8), 631–639.

(47) Brusseau, T. a; Kulinna, P. H. An Examination of Four Traditional School Physical Activity Models on Children’s Step Counts and MVPA. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2015, 86 (1), 88–93.

(48) Belansky, E. S.; Cutforth, N.; Delong, E.; Ross, C.; Scarbro, S.; Gilbert, L.; Beatty, B.; Marshall, J. a. Early Impact of the Federally Mandated Local Wellness Policy on Physical Activity in Rural, Low-Income Elementary Schools in Colorado. J. Public Health Policy 2009, 30 Suppl 1 (1), S141–S160.

(49) Patino-Fernandez, A. M.; Hernandez, J.; Villa, M.; Delamater, A. School-Based Health Promotion Intervention: Parent and School Staff Perspectives. J. Sch. Health 2013, 83 (11), 763–770.

(50) Consiglieri, G.; Leon-Chi, L.; Newfield, R. S. Policy Challenges in the Fight against Childhood Obesity: Low Adherence in San Diego Area Schools to the California Education Code Regulating Physical Education. J. Obes. 2013, 2013, 483017.

(51) Beam, M.; Ehrlich, G.; Donze, J.; Block, A.; Leviton, L. Evaluation of the Healthy Schools Program: Part I. Interim Progress. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2012, 9 (17), 9–14.

(52) Delk, J.; Springer, A. E.; Kelder, S. H.; Grayless, M. Promoting Teacher Adoption of Physical Activity Breaks in the Classroom: Findings of the Central Texas CATCH Middle School Project. J. Sch. Health 2014, 84 (11), 722–730.

Explore More:

Healthy Families & SchoolsBy The Numbers

142

Percent

Expected rise in Latino cancer cases in coming years