Share On Social!

Zo Mpofu believes protecting the health of mothers and babies in childbirth is a moral responsibility.

That is why it alarmed Mpofu, a human services program consultant for Buncombe County Department of Health and Human Services in North Carolina, that local black women are 3.8 times more likely to lose their baby in the first year of life than white women.

Also, Dakisha “DK” Wesley, assistant county manager in Buncombe County, worried that black people accounted for 25% of the jailed population, despite being 6.3% of the local population.

Mpofu and Wesley believe these are the results of structural racism.

That is why these government employees collaborated with cross-sector partners to urge Buncombe County leaders to pass three resolutions declaring racism a public health and public safety crisis.

What’s unique is the path they took to get there — and how it’s working.

Mpofu and Her Growing Interest in Local Policy to Improve Health

Mpofu has always cared deeply about people in her hometown, Asheville, the county seat of Buncombe County in North Carolina.

So much so, she returned to her community after living in New York, where she served as a U.S. House Staff Member, helping drive policy change in affordable housing, youth development, and healthcare.

But she noticed that many North Carolina state and local policies weren’t actually solving problems for historically disadvantaged populations in her community.

“Many resources aren’t meeting people due to historic and systemic discriminatory practices,” Mpofu said.

This was a problem for Mpofu. She knows public health is extremely local. She knows equity and inclusion in local decision-making are essential to improve health outcomes.

After she started working for Buncombe County in 2016, she recognized the importance of a cross-sector, systems approach to understand and impact equity, inclusion, and public health.

Mpofu thinks that local government workers, like herself, play a crucial role in identifying and addressing the impact racism has on health and community context.

A priority in that effort is infant mortality.

Infant mortality is a gold standard indicator for overall community health. Disparities in infant mortality are an early-warning sign for racism, as structural issues in healthcare and social service delivery contribute to poor quality care for mothers of color.

“If our residents can’t make it to their first year of life for something that is preventable, there is much we have to do at a policy and systems level,” Mpofu said.

Wesley and Her Growing Interest in Local Policy to Improve Health

Wesley considers herself a public servant.

At first, after she completed her master’s degree in public administration, she knew she wanted to serve in local government. She just wasn’t sure how.

“I’ve always taken to public service,” Wesley said. “Not so much politics, but the more practical side of public service.”

She happened to fall into governmental budgeting.

As a budget analyst in the City of Fort Worth, Texas, she learned about everything from courts, court technology, public safety, infrastructure, human services, and other social issues. She also led diversity and inclusion efforts in all her roles.

“When in the budget office, you learn a bit about all governmental operations and you try to get involved and obtain an understanding to help departments with financial planning,” she said.

Now, with Buncombe County, Wesley is the executive sponsor for equity and inclusion and manages the community and justice services departments, which includes:

- City/County Identification Bureau (i.e., criminal identification, gun permitting)

- Communications and public engagement

- Election services

- Emergency services

- Health and human services (i.e., public health, social work services, and veteran services)

- Justice services (i.e., treatment courts, jail diversion programs, jail reentry services, pre-trial services, and family justice center)

- Library

- Recreational services (i.e., parks, greenways)

- Strategic Partnerships (i.e., community investments, grants, and collaborative projects)

Wesley recognizes that how the justice system is set up results in people getting disparate justice, which is connected to worse health outcomes.

Approximately 22% of North Carolina’s population is black. Yet of those serving more than 20 years in prison, 52.5% are black, according to the North Carolina Task Force for Racial Equity in Criminal Justice.

“If our society and criminal justice system were producing racially equitable outcomes, we would find a similar breakdown in arrest rates, prison population, and sentencing decisions [between white and black populations],” the task force reports. “But we do not.”

That’s why Wesley relies on data to illustrate disparate outcomes.

“Stories about criminal justice are often emotional. But we have to make sure we have the quantitative piece to align with those qualitative stories,” Wesley said. “We have some of the worst numbers in violence and murder in the state.”

Wesley also recognizes that childhood trauma is connected to both involvement in the justice system and worse health outcomes.

“Both trauma exposure and trauma-associated mental health disorders are associated with an increased likelihood of Black American adults being arrested and incarcerated,” according to the task force.

Like Mpofu, Wesley thinks that government professionals, like herself, play a crucial role in identifying and addressing the impact racism has on health, particularly through public safety and criminal justice.

“We need people working from inside the system to look at it differently. The push from local advocacy groups is essential but it also takes a pull from the inside. Taking a critical look at the systems we work in takes both care and courage,” Wesley said.

How Racism Impacts Public Health

Mpofu and Wesley believe the problem is that past and present discriminatory policies and practices created inequities in the social determinants of health.

Social determinants of health are the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age.

Social determinants include whether an individual lives in adequate housing, free from violence, discrimination, and toxins, with access to quality childcare and education, employment, healthy food, physical and mental health care, social support, financial resources, and justice services, as well as safe transportation options connecting to these places and resources.

With inequities, neighborhoods of color often lack access to opportunity, which contributes to social and economic factors that lead to health disparities, such as poverty, unemployment, transportation-cost burden, food insecurity, low educational attainment, and involvement in the justice system.

Together, the social risk factors that arise from these conditions and associated individual behaviors account for roughly 60% of U.S. health care costs, less than genetics (30%) and health care (10%).

Whether implicit or explicit, racism in policymaking, investment decision-making, and individual interactions contributes to these social risks and harms health.

How could Mpofu and Wesley begin to address these issues?

Mpofu Targets Infant Mortality in Buncombe County

Infant mortality seemed the right place to start.

The infant mortality rate is one of the key indicators public health professionals use to gauge the overall physical health of a community, according to Mpofu.

At 6.4 infant deaths per 1,000 live births, infant mortality in Buncombe County is higher than the nation.

To put infant mortality in the U.S. into perspective, there were 5.8 infant deaths for every 1,000 live births in the U.S. in 2017. That is a higher rate than Canada, France, the United Kingdom, Belgium, Netherlands, Switzerland, Australia, Germany, Austria, Sweden, and Japan.

The U.S. also has double the maternal mortality ratio than nearly all these countries, too.

High infant mortality rates are particularly worrisome because of racial/ethnic disparities:

- 8 deaths per 1,000 live births among African Americans

- 4 deaths per 1,000 live births among Native Americans or Other Pacific Islanders

- 2 deaths per 1,000 live births among American Indian or Alaska Natives

- 9 deaths per 1,000 live births among Latinos

- 6 deaths per 1,000 live births among Whites

- 6 deaths per 1,000 live births among Asians

Mpofu considers disparities in infant mortality a “canary in the coalmine” for past and present racial discrimination.

She uses this metaphor because in the mid-1900s, canaries were used as an early-warning sign to detect carbon monoxide in coalmines. Canaries are more sensitive than humans to this odorless, colorless gas that can build to deadly levels in coalmines.

That’s one of the main reasons Mpofu sought to leverage various local opportunities to address discriminatory policies and practices.

Even those who aren’t working in infant and maternal health should care about this early-warning sign because it tells us a lot about how healthy we will be as a population overall, Mpofu said.

Mpofu Builds Support for Addressing Infant Mortality, Racism

Mpofu’s work in the community often involved Frank Castelblanco.

Castelblanco is a doctor of nursing practice and chair of the Department of Continuing Professional Development with the Mountain Area Health Education Center (MAHEC) in Buncombe County, which conducts educational programs and conference for healthcare professionals.

Castelblanco served with Mpofu on the Community Health Improvement Process (CHIP) Advisory Board. He was chair of the Buncombe County Health and Humans Services Board, a position appointed by the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners.

He was also familiar with infant mortality disparities.

“In Buncombe County, infant mortality rates for African-American babies are more than twice as high as rates for white babies,” Castelblanco said. “For a lot of babies, their health is determined before they are born.”

These disparities are, again, rooted in racist policies and practices that create inequities.

“Our OBGYN takes care of these babies and it is incredibly frustrating for them to see these inequities,” said Castelblanco.

Through Mpofu and Castelblanco’s work on the Community Health Improvement Process (CHIP) Advisory Board, they decided to focus on two priorities for the county:

- Infant mortality

- Mental health

“We landed on the two canaries that are embraced by the World Health Organization ‘WHO’ that indicate how healthy your community is: infant mortality and birth outcomes, specifically racial disparities; and mental health, to include adverse childhood experiences,” Mpofu said.

Mpofu and Castelblanco began ensuring that they considered racism, equity, and inclusion in all conversations about public health with all cross-sector partners.

In parallel, Wesley was working with local leaders on similar issues — in public safety.

Wesley Targets Public Safety, Community Justice

When Wesley began working in Buncombe County, she was launched into the county’s first-ever process to develop and adopt a strategic plan.

“My first day with Buncombe County was the first session of the strategic plan development,” Wesley said.

Two of the plan’s goals were:

- Reduce the jail population and enhance public safety

- Eliminate deaths as a result of substance abuse

Wesley not only wants to safely reduce the size of the jail population but reduce disparities in this population.

Of youths sentenced to life without parole between 1994-2018 in North Carolina, 8.5% are white and 80.9% are Black, according to the North Carolina Task Force for Racial Equity in Criminal Justice.

Wesley also wants to eliminate deaths as a result of substance abuse. She knows that children who grow up in a household with substance abuse are more likely also engage in substance abuse, which increases their risk for involvement in the justice system and leads to poor health outcomes.

To obtain public input on the strategic plan, county leaders held 13 community feedback sessions, two county employee surveys, and 15 county employee workshops.

During these sessions and workshops, county leadership heard an outcry from the community to include equity as a value in the strategic plan.

Thus, equity was added as a fifth value along with respect, integrity, collaboration, and honesty.

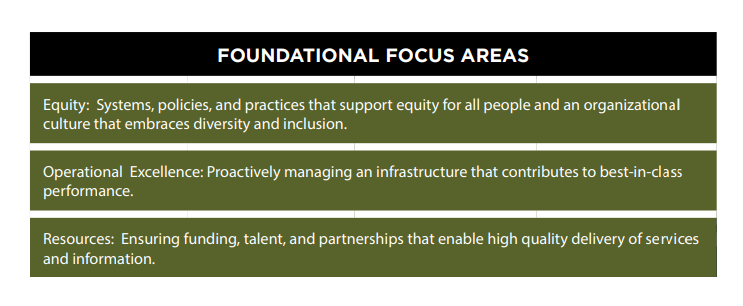

Additionally, equity was added as a foundational focus area. Including equity as a foundational focus area means questioning systems, policies, and practices.

“Sometimes we move too fast and do it the way we always did it, but we have to slow down and ask ourselves these questions,” Wesley said.

She also pushed for a goal to implement land use strategies that encourage affordable housing near transportation and jobs. This is important and related to racism because of a history of discriminatory practices in land use and transportation policies and practices.

“We spent a lot of time training department heads on structural racism and government policies that result in disparate outcomes and displacement of BIPOC communities, like urban renewal,” Wesley said.

In May 2020, the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners adopted the 2020-2025 Strategic Plan. They soon directed the Equity and Inclusion Workgroup to ensure policies and practices eliminate barriers and allow for equitable opportunity and ensure representative and inclusive practices are reflected in decision making.

Both Mpofu and Wesley serve on the Equity and Inclusion Workgroup.

Wesley Builds Support for Addressing Public Safety, Community Justice, Racism

Based on the data that was being presented by county staff, Wesley also began to ask equity questions as a member of the Justice Resource Advisory Council (JRAC).

JRAC an advisory body that was established by the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners in 2018 to focus on systemic planning and coordination to ensure policies and programs are cost effective, efficient, and produce maximum outcomes for the community.

The JRAC aims to safely reduce the jail population, divert individuals with mental illness and substance abuse into treatment, and address racial and ethnic disparities.

“The main mission is to bring stakeholders in the justice realm together to collaborate, share data, and come up with strategies to improve the criminal justice system as well as inform and advise the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners,” Wesley said.

Membership in JRAC is based on position, representation, and appointment. This means some are members because they hold a staff position within a certain department or agency, such as the Buncombe County Manager’s Office, Buncombe County Health and Human Services, Asheville City Manager’s Office and the local behavioral health agency. Others are members because they hold an elected position, such as the Sheriff, District Attorney, and Superior Court Judge. Additionally, some members are appointed by the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners.

“One office can’t do it by themselves,” Wesley says. “It takes everyone.”

Wesley supported the JRAC in strengthening their bylaws.

This includes a section establishing the objective to address jail population management in a holistic manner considering resources, safety, and disparities, as well as a section requiring the JRAC to develop and adopt a comprehensive criminal justice plan.

Wesley is currently the council chairwoman and continues to support the JRAC by elevating equity in the strategies and priorities they develop and recommend and by making connections to build a trauma-informed workforce.

“It is important that staff and law enforcement recognize and are prepared to have trauma-informed responses to residents,” Wesley said.

The Trend toward Declaring Racism a Public Health Crisis

Emerging research suggests that racism itself is a social determinant of health.

Systemic racism makes it harder for Blacks, Latinos, and other people of color to get healthcare, housing, transportation, education, employment, healthy food, safe treatment by police, and more.

This threatens health over the long-term.

That’s why leaders and communities across the country are declaring racism a public health crisis.

You can even use Salud America!’s action pack to help you start a conversation with city leaders for a resolution to declare racism a public health issue along with a commitment to take action to change policies and practices. It will also help build local support.

For Mpofu, these declarations stood out as a local solution to health problems, like disparities in infant mortality.

For Wesley, these declarations stood out as a local solution to disparities in community safety and criminal justice.

Mpofu and Wesley — through multiple ongoing community efforts and racial justice, public health, and other local leaders — were able to build connections and leverage opportunities that would ultimately culminate in three resolutions declaring racism a public health and safety crisis:

- Health and Human Services Board: Resolution Declaring Racism a Public Health Crisis

- JRAC: Resolution Declaring Racism a Public Safety Emergency

- Board of Commissioners: Resolution Declaring Racism a Public Health and Safety Crisis

Mpofu started with the Health and Human Services Board.

Health and Human Services Board: Resolution Declaring Racism a Public Health Crisis

Mpofu took the lead in exploring existing resolutions declaring racism a public health crisis.

However, only a handful of places had established these resolutions in early 2020.

“It was all new in terms of something that is written specifically about how racism is connected to health outcomes,” Mpofu said.

She looked at how these documents articulated racism and how the “whereas statements”— such as, “whereas, racism causes persistent racial discrimination influencing many areas of life, including housing, education, employment and criminal justice”— articulated observations and alignments and how “therefore statements” — such as, “therefore, be it resolved that Buncombe County Health and Human Services and Board will continually assess and revise all portions of codified health regulation through a racial equity lens”— articulated commitment to action. She examined the voice and tone as well as legal and philosophical grounding of the resolutions.

Mpofu also relied on resources from the Government Alliance on Race and Equity (GARE), Policy Link, and the County Health Rankings.

Then, Mpofu began an initial draft.

She started with the big ideas on racism and gave examples of what it looks at the national and state levels. Then, using local data, she explained what it means for Buncombe County.

She didn’t want a symbolic document, but a document that held Health and Human Services board members accountable.

“I wanted our ‘therefore statements’ to function as commitments to do more and to do better,” Mpofu said.

Mpofu included local data demonstrating inequities.

“In Buncombe County, 20.64 percent of White homeowners experience housing cost burden, while 39.4 percent of Black homeowners experience cost burden,” the resolution states.

Mpofu mentioned state efforts that aligned with the resolution.

“The North Carolina Public Health Association (NCPHA) recognizes the broad public health impacts of systemic racism and if we are to advance public health in our state and around the country, we must continue to work together to address these underlying issues,” the resolution states.

Mpofu mentioned local efforts that aligned with the resolution.

“The Buncombe County Board of Commissioners 2020-2025 Strategic Plan identifies equity as a foundational focus area with a commitment to systems, policies, and practices that support equity for all people and an organizational culture that embraces diversity and inclusion,” the resolution states.

Mpofu also included actionable commitments. For example:

- Conduct an assessment of internal policy and procedures and make recommendations to the County Manager and Board of Commissioners of changes needed to ensure racial equity is a core element of Buncombe County Health and Human Services.

- Conduct an assessment and make recommendations to the County Manager and Board of Commissioners of changes needed to incorporate into the organizational structure a plan for education efforts to understand, address and dismantle racism, in order to undo how racism affects individual and population health.

- Continually assess and revise all portions of codified health regulations through a racial equity lens.

- Identify clear goals and objectives, including specific benchmarks, to assess progress and capitalize on opportunities to further advance racial equity, aligning measures with indicators identified in the Healthy NC 2030 Report.

Mpofu shared the draft resolution to declare racism a public health crisis with other Health and Human Services staff. They were very supportive.

She also recognized how public health and safety are connected.

She shared the draft with Wesley.

“It is interesting how conversations on health continue to show up with how we define public safety,” Mpofu said. “If you think about everything that has happened during COVID-19, the public health crisis turned into a law enforcement crisis to enforce public health guidance, like masks and business closures.”

JRAC: Resolution Declaring Racism a Public Safety Emergency

After seeing Mpofu’s draft resolution, Wesley thought the JRAC could commit to identifying and addressing the impact racism has on public safety the same time the Health and Human Services Board committed to identifying and addressing the impact racism has on public health.

The JRAC Safety and Justice Challenge Racial Equity Workgroup was already doing deep equity work and was posed to dive into leading this effort by drafting a workgroup statement. Using the workgroup’s statement as a foundation, Wesley began working on a draft resolution to declare racism a public safety emergency with then Chief Public Defender and JRAC vice chair, LeAnn Melton, Buncombe County Sheriff Quentin Miller, and other JRAC members.

Like Mpofu’s draft, Wesley and Miller included data to demonstrate inequities.

For example: “Despite well-established national research data that White and Black Americans use drugs, sell drugs and engage in other criminal activity at approximately the same rates, in Buncombe County Black Americans have an incarceration rate that is nearly four times greater than White Americans.

Like Mpofu’s draft, they also mentioned how state efforts align with the resolution, such as the state’s recent executive order (No. 145) that acknowledged racial inequities in law enforcement and criminal justice and established a task force to address systemic racial bias in criminal justice.

Wesley and Miller also mentioned local efforts that align with this resolution, such as the 2025 Strategic Plan and the Equity and Inclusion Workgroup.

They also included actionable commitments for the JRAC to:

- Train at least 75% of system staff criminal justice actors in racial equity and implicit bias training.

- Use racial equity tool to review and revise local criminal justice policies, procedures, and practices that create disparate outcomes.

- Ensure complete and regular availability of specific race and ethnicity data that documents racial disparities that exist in the criminal justice system.

“When our board adopted the strategic plan in May 2020 that included equity as a foundational goal and value, that was my marching orders to move forward with this,” Wesley said.

Mpofu and Wesley Get Resolutions Passed to Declare Racism a Public Health, Public Safety Crisis

Although the idea of a resolution declaring racism a public health crisis was new, the concept that racism impacts health was not new.

“Because of the conversations and work that were already happening in Buncombe County and because of the national outrage about George Floyd, the idea of a resolution declaring racism a public health crisis was widely accepted,” Mpofu said.

The idea of a resolution declaring racism a public safety emergency was also widely accepted.

Mpofu formally presented the resolution to declare racism a public health crisis to the Health and Human Services Board. It was adopted on June 26, 2020.

Accordingly, the complimentary resolution to declare racism a public safety emergency was presented to JRAC. It was adopted July 10, 2020.

“Because we implemented the strategy to employ cross-sector collaboration, we were able to get this historic policy measure adopted,” Mpofu said.

The Role of Advocates and Elected Leaders in Declaring Racism a Public Health Crisis

Boards and advisory councils can play an essential role in denouncing racism, intolerance, and exclusion in the operations and decisions of the agencies and organizations they oversee.

They can ensure more equitable strategic planning and more equitable internal practices within agencies and organizations.

However, there is an important distinction between boards/advisory councils of agency departments and a board of commissioners.

Members of boards of commissioners are elected officials while members of boards/advisory councils are generally appointed officials.

For example, members of the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners are elected by residents of Buncombe County. Meanwhile, members of the Buncombe County Health and Human Services Board are appointed by the Board of Commissioners, and members of JRAC are established based on position/representation which was determined by the Board of Commissioners.

There is also an important distinction when it comes to accountability.

Boards/advisory councils often oversee specific departments or functions, like health or criminal justice, while boards of commissioners are often the highest policymaking body in the county.

Mpofu and Wesley wanted the highest policymaking body in the county to adopt a joint resolution declaring racism a public health and safety crisis commit to actions to confront racism and promote and support polices that prioritize the health of all people.

“It’s connecting the dots to local action,” Mpofu said. “People have underestimated how local public health is, and leaders have to be held accountable for it.”

Board of Commissioners: Joint Resolution Declaring Racism a Public Health and Safety Crisis

On July 21, 2020, the Health and Human Services Board and JRAC submitted a formal request to the Buncombe County Commissioners for a joint resolution declaring racism a public health and safety crisis.

The resolution included critical elements of the previous two resolutions and established the creation of an equity action plan and data collaborative to publicly track equity data.

“The County Manager has established a cross-departmental Equity & Inclusion staff workgroup to design, coordinate and organize a community-informed Equity Action Plan that includes an equity data governance collaborative to collect, monitor, evaluate and publicly display relevant data,” the resolution states.

Again, because of the conversations and work that was already happening in Buncombe County, the resolution was widely accepted and passed unanimously.

“For years they have seen disparities, so this was music to their ears,” said Castelblanco, then chair of the Health and Human Services Board.

The proposed resolution was also widely accepted because the request included 18 letters of support from the following partner agencies:

- AB Food Policy Council

- ABIPA

- Avery Health Education and Consulting

- Buncombe Aging Services Alliance

- Buncombe Partnership for Children

- Human Relations Associates, Inc.

- MAHEC

- Mothering Asheville

- MountainTrue

- NC Center for Health & Wellness

- Pisgah Legal Services

- Resources For Resilience

- Story Medicine for Racial Healing Learning Community

- VAYA Health

- Western Carolina Medical Society

- WNC Regional Health Educators

- YMCA of WNC

- YWCA of Asheville and WNC

The resolution declaring racism a public health and safety crisis was approved on Aug. 4, 2020.

This was the first in the southeastern region of the country.

Now, there are multiple resources from the Network for Public Health Law and our team at Salud America!, to support communities in declaring racism a public health crisis. As of July 2021, 226 leaders and entities have declared racism a public health crisis.

The Network for Public Health Law also examined 21 resolutions in the southeastern region.

Of those, the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners joint resolution is one of nine to “reference the use of data to drive changes in policy and decision-making, inform evidence-based interventions, illustrate health disparities, or track progress” according to a Network for Public Health Law issue brief.

Additionally, the joint resolution is one of only four that references public safety or policing.

Interestingly, of the 21 resolutions, the Health and Human Services resolution is one of two resolutions that commits to assessing policy using an equity lens, one of two resolutions that references trauma or community stress, and one of six resolutions that commits to engage actively and authentically with communities of color.

“We couldn’t have done this if we weren’t informed on ACEs and hadn’t prioritized racial disparities and mental health in the numerous other efforts we were part of,” Mpofu said.

First Steps in Fulfilling the Resolutions in Buncombe County

Per the Health and Human Services Board resolution calling for staff to conduct an assessment of internal policy and procedures and make recommendations to the County Manager and Board of Commissioners, the Equity and Inclusion Workgroup adopted a results-based accountability model for evaluating progress in equity and inclusion.

The model was initially adopted by GARE to measure, plan for, and advance racial equity in the government setting. Health and Human Services is working with a consulting firm to host trainings for the model.

Additionally, the same week the resolution passed, the county hired a new public health director.

“I anticipate a future with more robust and innovative strategies for health equity with our new public health director, Stacie Saunders, at the helm,” Mpofu said.

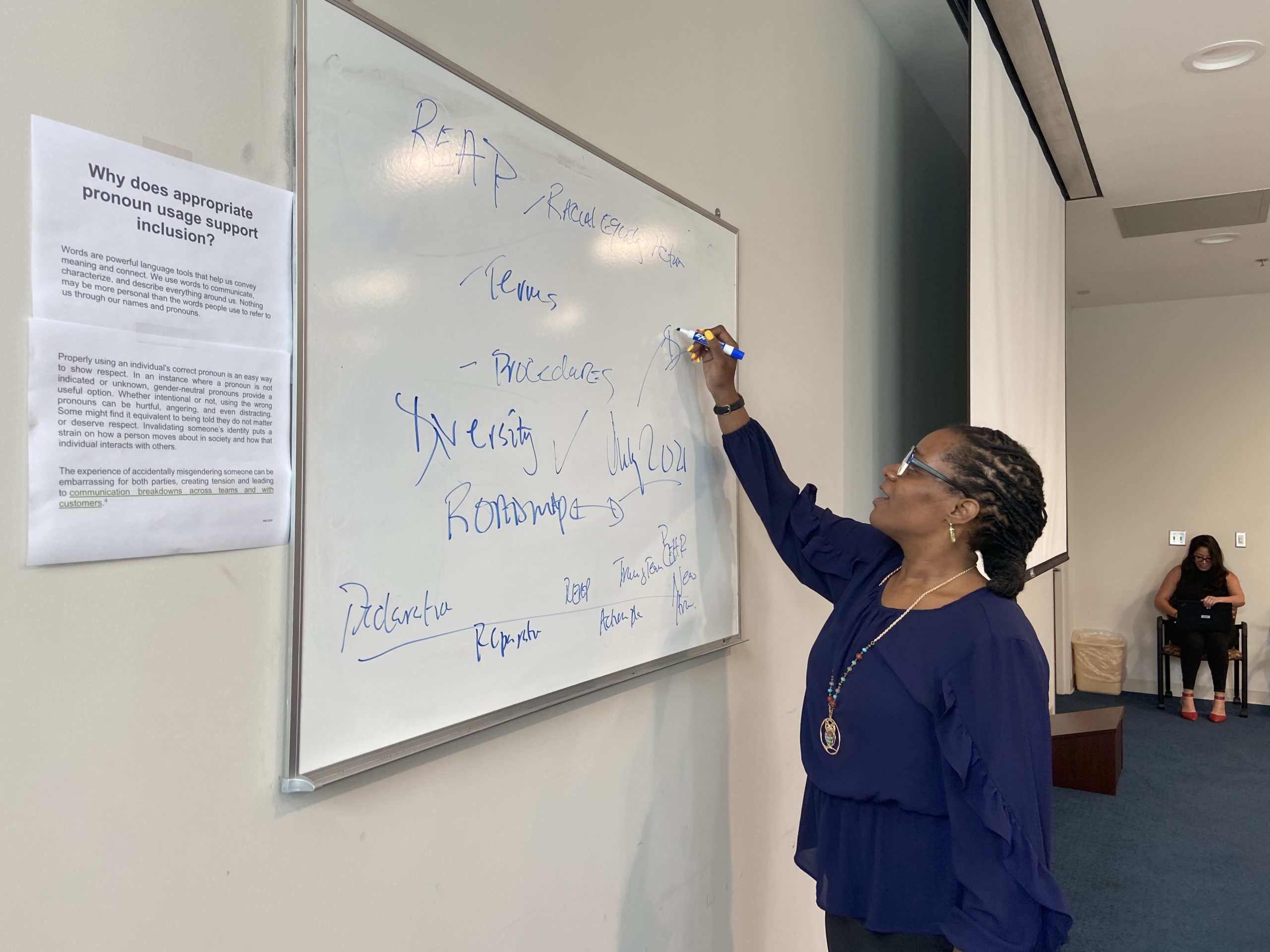

Per the JRAC resolution calling to train at least 75% of system staff criminal justice actors in racial equity, structural and systemic racism, and implicit bias the county hired an equity and inclusion consultant to develop and implement trainings.

Additionally, per the JRAC resolution calling to implement courageous, innovative, and holistic solutions that enhance community safety and reduce racial disparities across the criminal justice system, the county launched a multi-disciplinary team, including a trauma-informed specialist, community health worker, and a youth mentor, to work with community members to increase community healing and decrease violence.

Per the Board of Commissioners joint resolution calling for the Equity and Inclusion Workgroup to design, coordinate, and organize a community-informed equity action plan, Mpofu, Wesley, and the Equity and Inclusion Workgroup began drafting an equity action plan with the community.

They relied on resources from GARE to draft an equity action plan and organized more than 10 community input sessions, each of which offered live Spanish translation. The workgroup also met with small groups of environmental, equity, justice, faith, health, wellness, education, economic, housing and youth partners, and the Latinx community.

Additionally, the County invested $25,000 to train staff on strategic planning, implementation, and evaluation.

“Early dollars are being invested to build our equity-capacity muscle at the county-government level,” Mpofu said.

The County also included a new position in the FY 2022 operating budget.

The newly established Chief Equity and Human Rights Officer will lead the development, implementation, monitoring, and improvement of local government policies, programs, and initiatives that promote antidiscrimination, anti-racism, diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts in the County.

Racial Equity Action Plan

The Racial Equity Action Plan drafted by the Equity and Inclusion Workgroup under Wesley’s leadership was adopted by the Board of Commissioners on June 15, 2021.

The plan aims to:

- Create pathways to ensure engagement in racial equity strategies that improve quality of life

- Provide racial equity education and communication to the community

- Improve quality of life outcomes through racial equity initiatives

- Cultivate a thriving workforce within Buncombe County that ensures racial equity

- Institute organizational policies and processes to ensure equity and accountability

- Establish Buncombe County as an equity inclusion model

“While the 2025 Buncombe County Strategic Plan places equity as both a foundational focus area and a value, none of the stated goals or objectives can be met without first developing a Racial Equity Action Plan to help us create the path there,” the Racial Equity Action Plan states.

The plan includes strategies and specific performance measures.

Strategies include:

- Implement strategies to reduce racial disparity in infant mortality and birth outcomes.

- Enhance community safety by providing trauma-informed criminal justice responses for the Black community.

- Promote development along existing public transportation routes, through land use regulations and development incentives.

- Support workforce development programs that increase graduation rates.

- Partner with community, schools, and justice system to end the school-to-prison pipeline and prevent youth from entering the criminal justice system.

- Provide diversity, equity, and inclusion professional development sessions for all staff.

- Create a transparent data system that reports and analyzes all equity, diversity, and inclusion progress/regression.

“One strategy in the equity action plan is that all policy systems changes, requests for budget, and ordinance updates have to go through an equity analysis tool to determine who benefits and who will be burdened,” Wesley said.

Performance measures include:

- % of staff participation in diversity, equity, and inclusion professional development sessions

- % of BIPOC youth vs. all youth involved in the juvenile justice system

- Average wage of workforce program graduates entering employment

- # of units of affordable housing in proximity to public transit

- % of fixed route and deviated fixed route mileage in historically marginalized communities

- # departments trained on equity data methodologies

- # policies created/revised with equity lens

The Equity and Inclusion Workgroup will share updates on the Racial Equity Action Plan with the Board of Commissioners at least twice a year.

This workgroup is creating a public-facing dashboard of key performance indicators to demonstrate to the community how well or not well they are doing.

Reporting directly to an Assistant County Manager, like Wesley, the newly established Chief Equity and Human Rights Officer will serve as a key liaison for the implementation of the Racial Equity Action Plan.

“We have a mandate now from the community in the strategic plan, from commissioners in the resolution, and from county leadership in the Racial Equity Action Plan,” Wesley said.

The Next Steps for Racial Equity in Buncombe County

Mpofu and Wesley are continuing their cross-sectoral efforts toward racial equity.

Mpofu wants to organize an annual “State of Equity and Inclusion,” much like a State of the City address, State of the County address, State of Housing, or State of Transit address.

This can unite elected officials and other stakeholders together to share what is helping, what is hurting, and what they can improve on.

“Whenever engaging in any collective effort, ceremonies and rituals are important,” Mpofu said. “If we can create a ritual on accountability and the work we are doing in equity, it can be unifying, build cohesion, and drive capacity or dollars to programs.”

Mpofu still focuses on infant mortality.

“We sometimes describe, when working with community partners and stakeholders, why does infant mortality matter to me if I’m not working infant and maternal health,” Mpofu said. “We remind folks that infant mortality continues to be gold standard indicator for community health overall.”

Wesley and Mpofu continue to drive conversations around equitable public health and safety with partners.

“If everyone has opportunity to thrive in our county, it makes us a better county,” Wesley said. “A rising tide lifts all boats.”

By The Numbers

23.7

percent

of Latino children are living in poverty

This success story was produced by Salud America! with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The stories are intended for educational and informative purposes. References to specific policymakers, individuals, schools, policies, or companies have been included solely to advance these purposes and do not constitute an endorsement, sponsorship, or recommendation. Stories are based on and told by real community members and are the opinions and views of the individuals whose stories are told. Organization and activities described were not supported by Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and do not necessarily represent the views of Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.