Share On Social!

“I feel like my life is threatened at each intersection.”

That is what Andreas Addison said about walking the streets and relying on mass transit during his #NoCarNovember experiences in Richmond, Va., where he is a city council member.

He wanted safer streets and more frequent transit for his constituents.

So Addison found two models he liked─a D.C. city leader’s omnibus bill (one that combines several measures into one package) for better transit, more walkability, and less car reliance, and Virginia Commonwealth University’s work to make campus safer for pedestrians.

Addison then began working on an omnibus bill of his own to create a safer environment for people walking, biking, and taking the bus in Richmond.

Unfair Social and Health Outcomes in Richmond

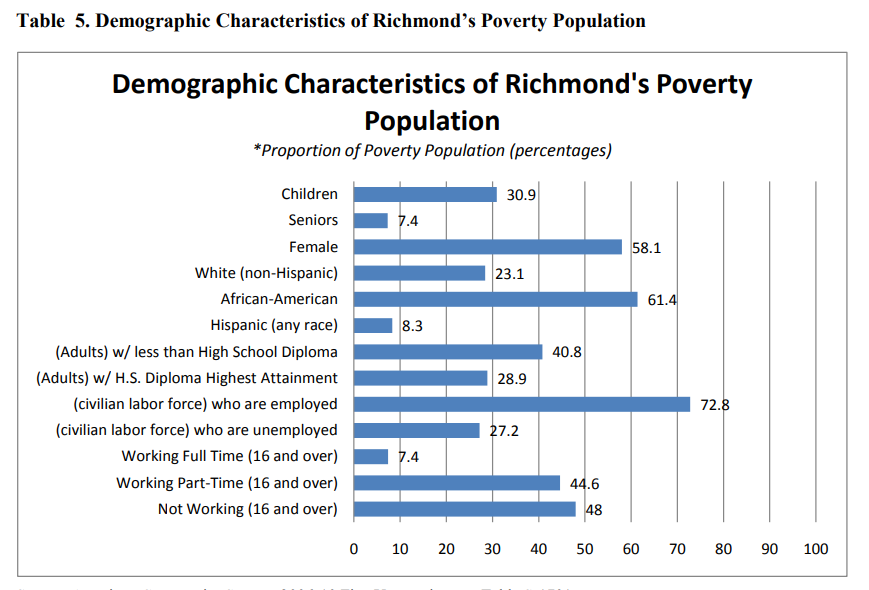

Life isn’t easy for Richmond’s Latino (7.1%) and African American (47.8%) populations.

- Latinos are 2.5x as likely to live in poverty than whites; African Americans 2x as likely.

- 36.2% of Latino kids live in poverty (5.7% of white kids).

- Unemployment is higher for Latinos (16.1%) and African Americans (14.3%) than whites (5.1%).

- 83,532 live in food deserts.

And that’s not to mention the transportation issues.

Nearly 17% of Richmond households do not have a motor vehicle.

Not enough people have safe routes for walking and biking, and transit that is frequent and accessible. These are crucial to connect to families to jobs, schools, parks, grocery stores, medical appointments, and other services.

“The city is growing, but our transportation network isn’t keeping up,” Addison said. “In a historically segregated city, divided by a river, it can be very isolating for minority families.”

A key strategy for long-term poverty reduction is to reduce the geographic isolation of high-poverty neighborhoods by expanding transit access to major employment centers region-wide.

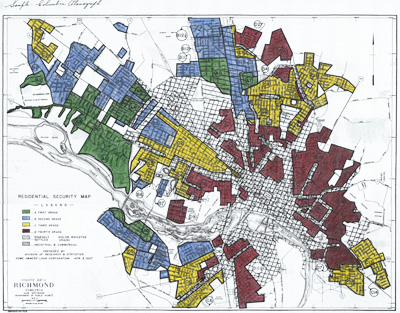

However, Richmond has history of bad transportation decisions.

A History of Bad Transportation Decisions in Richmond

Richmond has history of poor transportation decisions.

On one hand, the city started the nation’s first electric trolley.

But by the 1940s, the trolley system failed after it was bought out by General Motors, which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1949 was a corporate conspiracy to obtain control of local transportation companies to monopolize the sale of supplies in the auto industry.

“We had great network back in 1900s, but at the onset of the car, we destroyed our entire public transit network, and we didn’t replace it,” Addison said.

A breakthrough came in 1973 with the Greater Richmond Transit Company (GRTC), but only modest improvements came with it over the next 45 years, according to a 2019 report on Richmond’s transit revolution.

How Job Access Impacts Transportation in Richmond

Thad Williamson, a University of Richmond professor and author of the mayor’s Anti-Poverty Commission Report, said the lack of quality transit is a top challenge in Richmond.

Acquiring and operating a private vehicle in an urban area is a substantial, ongoing expense, which is why so many households in Richmond don’t a vehicle.

Transit access improves job access, which is critical to reduce poverty.

Unfortunately, Richmond is very weak on two distinct measures of job access:

- the proportion of jobs that are covered by transit in the first place; and

- the proportion of the working-age population that can access those jobs that are covered by transit, according to the Report.

Richmond has one of the most severe spatial mismatch problems in the nation. The metro area ranks 92nd among the 100 largest U.S. metropolitan areas for access to transit and jobs.

Just 30.8% of working-age residents have access to transit compared to 51.4% in Memphis, 65.3% in New Orleans, and 89% in Salt Lake City, three metropolitan areas of similar size, according to the 2011 Missed Opportunity: Transit and Jobs in Metropolitan America report by the Brookings Institution.

“Expanding regional transit now is an opportunity to turn the page on this history of missed opportunities and embrace a future premised on the idea that the city and the counties share a common fate,” the report states.

Transit Changes Start to Rise, But Richmond Streets Remain Dangerous

2018 was a year of unprecedented change for transit in the Richmond area.

Leaders installed a new bus rapid transit line and comprehensive route redesign. Many agree these improvements—and subsequent 17% boost in transit ridership—are beneficial.

But most also say more progress is needed, especially for pedestrian safety.

“To do the #NoCarNovember challenge living south of the James would be difficult,” Addison said. “[Bus rapid transit] works but not for all of Richmond yet.”

REPORT

People need safe sidewalks and bike lanes to get to transit stops.

However, Richmond sidewalks are narrow, streets are not comfortable, and crosswalks are wide, Addison said.

Each year, roughly 2,700 people are injured and 13 people are killed on Richmond city streets, according to Mayor Levar M. Stoney in Richmond’s Vision Zero Action Plan.

The city’s High Injury Street Network shows 58% of all fatal and serious injury crashes occur on just 16% of roads. Half of all pedestrian fatalities and serious injuries occur at intersections. This suggests fatal crashes are not random but related to street design.

In 2017, 11 were people walking were killed by people driving.

“At intersections, drivers are not looking at me in the crosswalk because they are looking left to turn right,” Addison said of walking in Richmond. “I am physically able to walk eight blocks, but I feel like my life is threatened at each intersection.”

Addison was determined to help.

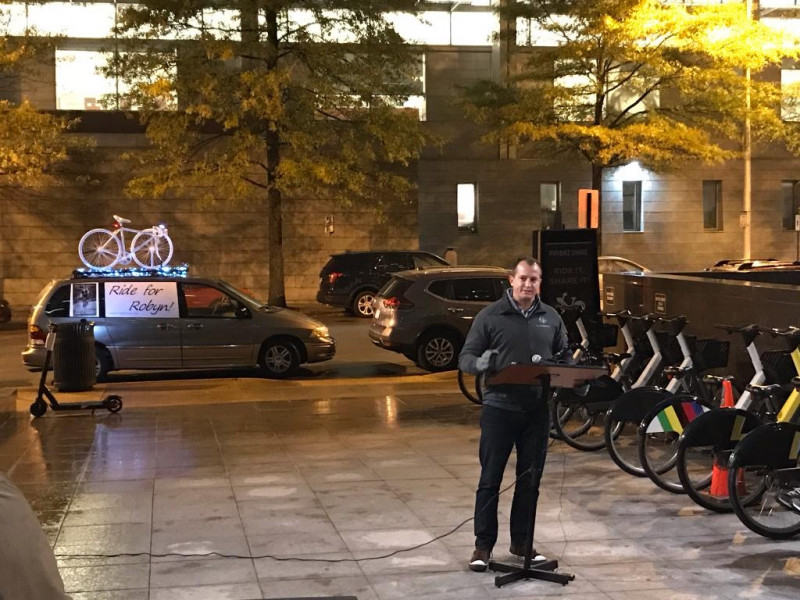

When he took office in 2017, signed Mayor Levar Stoney’s Vision Zero pledge for no deaths on Richmond roadways. To make sure he understands residents’ transportation struggles, he ditched his car to walk and bus places the entirety of November in 2018 and 2019.

“To be Vision Zero you need to redesign streets, but you also need to change the mentality of the driver, particularly about yielding” Addison said. “People speed up around people biking in a way that is unsafe because they are frustrated by the slightest delay. They don’t have a yield first mentality.”

Addison wants to better understand where and why crashes are happening on a systemic level to design safer streets and intersections, rather than blame the victim or the perpetrator.

Addison wants to change the system: lower speed limits and limits on right turns on red lights.

“Our cities talk about issues at each crash and location rather than talk about the bigger system,” Addison said.

A First Big Win: Lowering the Speed on a Dangerous Street

Residents living on Grove Avenue were concerned about people speeding.

The speed limit was 35 miles per hour (mph). But a driver going 50 mph recently crashed into a utility pole and knocked out the electricity on the one of the coldest days of the year, Addison said.

The residential street is lined with homes, and an elementary school, a daycare, and a church.

“Some older populations don’t even feel safe pulling out of their driveway because people are driving much too fast,” Addison said.

Of course, they don’t feel safe walking either.

On a similar residential street, the city’s public works department conducted a traffic study and found that, of the 1,600 vehicles counted, 85% averaged 45 mph, Addison said.

“That is way too many people driving over 45 mph on residential street,” he said. “The public works department even admitted people driving speeds high enough that exceeded the reckless driving threshold.”

Addison wants to protect his constituents against that.

In October 2017, Addison proposed an ordinance to reduce the speed limit on Grove Avenue from 35 to 30 mph.

City Council voted and passed the ordinance the following month.

Addison sees a lot more room for improvement on Grove Avenue and across Richmond.

For example, right now residents are pushing the city to add a four-way stop to a current two-way stop where people driving and walking have low visibility due to parked cars on Grove Avenue. The city’s traffic study said the intersection didn’t meet requirements for a four-way stop.

“The challenge with improving safety is getting all of the departments involved to work together and to work with police,” Addison said. “We can do best built environment, but if police don’t enforce speed, yielding, and parking, I can’t create the behavior change that makes Vision Zero possible.”

Addison Inspired by Virginia Commonwealth University Pedestrian Safety Improvements

Nearly 1.2 million vehicles trek through Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) campuses each week.

More pedestrian fatalities and serious injuries occur in the downtown area and on and connecting to VCU than the rest of the city, according to the Vision Zero Richmond Action Plan.

University leaders wants to reduce injuries and improve walkability.

As part of a large master plan, VCU is planning more walkable green space and safer crosswalks.

“Work to extend curbs at the intersections of Shafer and Franklin streets and Linden and West Main streets began this month and will reduce the crossing distance for pedestrians at those intersections from four lanes to two and create small plazas near both intersections,” VCU News reports.

Additionally, VCU students in a brand management class developed Vision Zero marketing campaigns that the city can adopt and easily implement. Once group of students conducted focus groups and interviews and came up with a road-safety jingle and colorfully painted crosswalks.

They presented their ideas to city and university leaders, including Addison, who are working to secure funding to support their recommendations.

Addison is interested to learn how street improvements and road-safety campaigns on campus will improve safety and how he can do that city-wide.

Addison Inspired by D.C. Councilmember’s Vision Zero Omnibus Bill

About 100 miles north of Richmond, in Washington, D.C., Ward 6 Councilmember Charles Allen knew local streets were not designed for safety. They were instead designed to move cars.

“It’s too easy to speed and plenty of intersections are a tragedy waiting to happen based on their design,” Allen said.

Allen wanted to make streets safer for people walking, biking, taking the bus, and driving. He especially wanted to protect the most vulnerable, those walking and biking.

So, he introduced the Vision Zero Omnibus Bill in May 2019 pushing for better infrastructure, stronger enforcement, and fewer automobile trips.

For example, the bill would:

- Ban right-on-red turns across D.C.

- Restrict speed limits to 25 mph on most minor arterial roads and 20 mph on local roads.

- Clarify that the mayor can impound cars parked illegally in crosswalks and bicycle lanes.

- Add requirement for DDOT to aggregate crash and speed data in one publicly accessible site.

- Require DDOT to certify plans for private developments that include new sidewalks, marking unmarked crosswalks, and adding protected bike lanes.

- Require annual progress report on all projects or recommended projects in the transportation plan, including explaining why recommended projects were not advanced.

- Require DDOT to update the transportation plan every two years, that will be approved by the Council, to include: A plan to get to 50% of commutes by public transit and an additional 25% percent by bike/ped by 2032; identifying areas in need of improved transit access; and identifying high-risk intersections.

More than 60 people testified at an October 2019 public hearing about the Omnibus Bill. They shared emotional stories about loved ones who were killed or seriously injured on D.C. streets. They shared fears about walking, biking, or driving on DC streets.

Some people spoke against the omnibus bill. John Townsend, a spokesperson for AAA Mid-Atlantic, argued that slowing down drivers would add frustration and create more problems.

Others said unsafe streets warrant a safer environment for people walking and biking.

“I am here today because I don’t smile when I ride my bike in D.C.,” said cyclist and advocate, Rachel Maisler at the hearing. “I don’t smile as a pedestrian, I don’t smile as a driver, or even as a public transit user. Instead, I practically cower in fear that this trip could be my last.”

The Vision Zero Enhancement Omnibus Amendment Act of 2019 is currently under council review.

“For a long time the criticism of the District has been that the city waits until there is a collision, until there’s an injury or death, and then it takes action,” Allen said according to the Washington Post. “The whole idea behind this legislation is: Let’s stop waiting until a life is lost.”

Addison wanted to stop waiting in Richmond.

Addison’s Omnibus Bill

Addison, inspired by VCU and D.C., worked with community groups, like Bike Walk RVA and Richmond Families for Safe Streets, and drafted an omnibus bill of his own.

“I’m a fan of putting the yield sign on centerline between lanes, like they do in Charlottesville, Virginia and Boston, Massachusetts,” Addison said.

Narrowing streets with curb extensions and narrowing lanes with signs in the centerline make it feel unsafe to go fast and these changes remind people driving that they share the space with people walking.

“I believe that the pedestrian crosswalks near [transit] stops should not only have leading pedestrian interval signals, but also a priority to cross sooner,” Addison said.

He says this because he missed multiple buses waiting to cross the street during his #NoCarNovember.

On Nov. 12, 2019, Addison introduced a omnibus package of five ordinances and five resolutions to make Richmond a safer and easier place to walk, bike, and take the bus.

The Safe Streets for All omnibus key ideas include:

- $60 fines for parking in bike lanes

- Banning right turns at red lights on city streets.

- Reduce the use of private vehicles by 50% within 12 years.

- Additional police enforcement on the city’s High Injury Street Network.

- Allowing bicyclists to treat stop signs as yield signs and red lights as stop signs.

- Increase public transit access in areas with below-average transit access rating.

- Establish a point system to determine intersection eligibility for all-way stop signs.

- Develop and implement a comprehensive plan for the collection and analysis of data.

- Reduced speed limits on Patterson Avenue and Libbie Avenue from 35 to 25 mph.

- Study the effects of “all walk” signals at intersections with the highest pedestrian traffic volumes.

- Prepare a plan for improving streetlight lumen standards along the city’s High Injury Street Network.

- Secure $3 million in funding for the Vision Zero traffic safety program for fiscal year 2021, and $2.2 million annually for the following five years.

- Publish and maintain a geographic information system map of the city’s High Injury Street Network showing areas with higher than average fatalities and serious injuries.

In early December 2019, City Council adopted 3 resolutions to improve the city’s pedestrian infrastructure; to develop and implement a comprehensive plan for the collection and analysis of certain data to be used to support the Vision Zero Action Plan; and to secure $3 million in funding for the Vision Zero traffic safety program for fiscal year 2021, and $2.2 million annually for the following five years.

“I’m excited about the entire package,” said Richmond City Council Member Mike Jones, according to Greater Greater Washington. “We’ve got to make an investment in our city to make sure people can safely walk and bike our streets. I hope that advocates of every age, color, and economic status will come out and fight for this Streets for All package.”

Council will vote in early 2020 on the remaining two resolutions and five ordinances:

- To support goals that promote sustainability and equity in access to safe transportation in the 2021 Richmond Connects Update, such as recommending projects that add new multimodal choices (transit, bicycle lane, sidewalk, etc.) and that provide a missing link to connect neighborhoods to meaningful destinations to reduce the use of private automobiles by 50% within 12 years. (Pending Council vote.)

- To establish designated no turns on red zones in City streets and to allow bicyclists to treat a stop sign as a yield sign and a red light traffic signal as stop sign. (Withdrawn. Department of Public Works is working to identify hazardous intersections.)

- To allow bicyclists to treat a stop sign as a yield sign and a red light traffic signal as a stop sign. (Passed. Waiting on General Assembly approval.)

- To reduce the speed limit on Patterson Avenue between Willow Lawn Drive and Pepper Avenue from 35 miles per hour to 25 miles per hour. (Pending Council vote.)

- To reduce the speed limit on Libbie Avenue between Guthrie Avenue and the City’s corporate boundary from 35 miles per hour to 25 miles per hour.(Pending Council vote.)

- To provide additional enforcement for contractors whose construction impedes upon the public right of way to restore all sidewalks, bike lanes and transit to at least their original condition within 3 days of the permit. (Passed.)

- To establish a point system upon which an intersection may become eligible for the installation of all-way stop signs. (Withdrawn.)

“I believe that these ordinances and resolutions provide our city with additional tools in the toolbox to meet the need of making our streets safer for everybody that travels them,” Bike Walk RVA Director Louise Lockett Gordon said of the ordinances sponsored by Addison during a public hearing, according to Rodrigo Arriaza of Richmond Magazine.

Addison is continuing to push for transportation improvements for all.

“We are changing the way our city thinks about getting around and about yielding to others trying to get around,” Addison said.

Explore More:

Transportation & MobilityBy The Numbers

27

percent

of Latinos rely on public transit (compared to 14% of whites).

This success story was produced by Salud America! with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The stories are intended for educational and informative purposes. References to specific policymakers, individuals, schools, policies, or companies have been included solely to advance these purposes and do not constitute an endorsement, sponsorship, or recommendation. Stories are based on and told by real community members and are the opinions and views of the individuals whose stories are told. Organization and activities described were not supported by Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and do not necessarily represent the views of Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.