Share On Social!

After more than 10 years of advocacy, New York became the first US state to approve a plan to charge drivers to enter highly trafficked areas during peak times, known as congestion pricing.

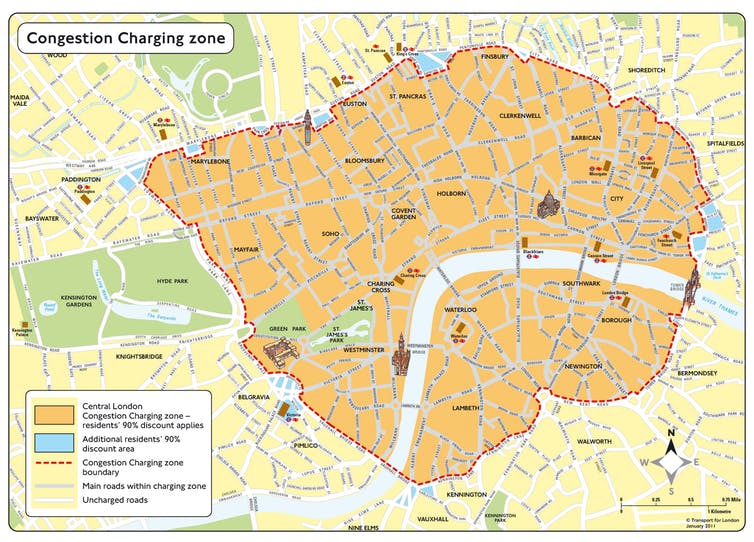

International metropolitan areas, such as London and Stockholm, have implemented similar fees for over a decade.

It took a transportation crisis in midtown Manhattan—where congestion slowed drivers to nearly a walking pace—for elected officials to act on congestion pricing.

The fees will go into effect by 2021 and will be dedicated to improving public transit.

Hidden Costs

The cumulative cost to drive a car is often the second largest household expense—which can be particularly burdensome for Latino families who are burdened by high housing costs and lack of safe, reliable transportation options, according to a Salud America! research review, The State of Latino Housing, Transportation, and Green Space.

However, the true direct and indirect costs required to sustain an auto-dependendence—over alternative forms of transportation—are far more costly.

States spend as much building new roads as they do repairing old ones, but aren’t able to keep the system in a state of good repair and meet the country’s growing travel needs. In 2014, various levels of government spent almost $165 billion to build, operate and maintain highways, according to the Committee for Economic Development (CED).

States spend as much building new roads as they do repairing old ones, but aren’t able to keep the system in a state of good repair and meet the country’s growing travel needs. In 2014, various levels of government spent almost $165 billion to build, operate and maintain highways, according to the Committee for Economic Development (CED).

Beyond infrastructure costs, driving has many indirect social and economic costs. Consider costs of crashes, subsequent fatalities, energy consumption, air pollution, environmental degradation, and diminished physical and mental health.

Roadway projects often overlook mobility for non-drivers as well as impacts on public health. This can isolate low-income families from opportunities, further contribute to emissions, and increase risk for pedestrian injuries and fatalities.

Congestion Costs

Congestion also takes a social and economic toll. Americans lose nearly 100 hours in congestion annually, costing the country $87 billion in time, according to a global study by transportation consulting firm INRIX.

Congestion and unreliability threaten truck transportation productivity and the ability of sellers to deliver products to market, according to the US Depatment of Transportation Federal Highway Administration (FHWA).

Failing to price congestion—and pollution, serious injuries, and deaths—makes driving too cheap, thus contributes to more congestion.

There is a consensus among economists that congestion pricing represents the single most viable and sustainable approach to reducing traffic congestion, according to the FHWA.

Congestion Pricing: You Drive It, You Buy It

Congestion pricing is a form of value-based pricing which isn’t new.

- Rideshare services charge more to ride during “surge” hours

- Airlines charge more to fly during peak travel days

- Cell phone carriers charge more to talk during peak hours

- Utility companies charge more to use electricity during peak hours

- Cities charge more for parking during peak hours

- Theaters charge more for tickets during peak hours.

Congestion pricing policies make roads subject to the market, which is not the case currently, as roads are highly subsidized.

The direct costs of driving are not proportional to spending on infrastructure to support driving, which means non-drivers are also footing the bill while being robbed of alternative transportation options.

For example, the federal gas tax hasn’t been raised in over 25 years. While construction and maintenance costs constantly rise, the purchasing power of the federal gas tax continues to decline.

Expenses associated with adding lanes in urban areas average $10 million per mile, yet funds generated from gas taxes on an added lane during rush hours amount to only $60,000 per year, according to the FHWA.

Ultimately, congestion is due to a failure to manage demand.

Value-based pricing helps manage demand. When used as a pricing tool, this method helps generate funds for bike, transit improvements and better transportation choices—particularly for non-drivers and vulnerable populations.

Cities across the globe are using cordon congestion pricing strategies, which is a fee or tax paid by users to drive in a congested area, compared to variable pricing on toll roads. American metropolitan areas, too, are considering the move to this method.

London passed a cordon congestion pricing policy in 2003 that, according to a 2011 case study, contributed to:

- 20% reduction in vehicles in the charging zone

- 83% increase in bicycle trips

- 100,000 fewer tons of carbon dioxide emissions annually

- 40-70 fewer traffic causalities annually

New York Won Congestion Pricing

New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg first endorsed congestion pricing in 2007. However, polls showed that the idea was not popular.

It took a crisis in New York’s public transit, which disproportionately affected communities of color, to begin shifting public and political will, according to Hayat Norimine with Sightline Institute.

Without reliable transit, more people were driving, and congestion got worse, slowing drivers to nearly a walking pace.

Over just two years, the average number of subway delays increased from 25,000 to 75,000 per month, according to Normine.

Activists used this information to build momentum and approach advocacy from both the top-down and bottom-up perspectives.

While the Riders Alliance’s grassroots movement brought peoples’ stories to the political forefront, groups such as the Regional Plan Association, Tri-State Transportation Campaign, and Environmental Defense Fund worked behind the scenes to gather votes, according to Norimine.

Labor unions even protested two opposing state officials at a news conference.

During this time, New York passed a rule adding a $2.50 fee to yellow taxi rides and a $2.75 fee to other rideshares, like Uber and Lyft, in busier parts of Manhattan. The funds will go towards improving transit.

They knew they needed to do more.

Advocates had to address perceptions that congestion pricing disproportionately affects low-income drivers as well as concerns about how funds from the proposed fee would be spent.

One solution was to provide a tax credit to residents in the congestion zone earning less than $60,000. Other ideas and more specific details will be worked out in the future with input from a newly formed Traffic Mobility Review Board.

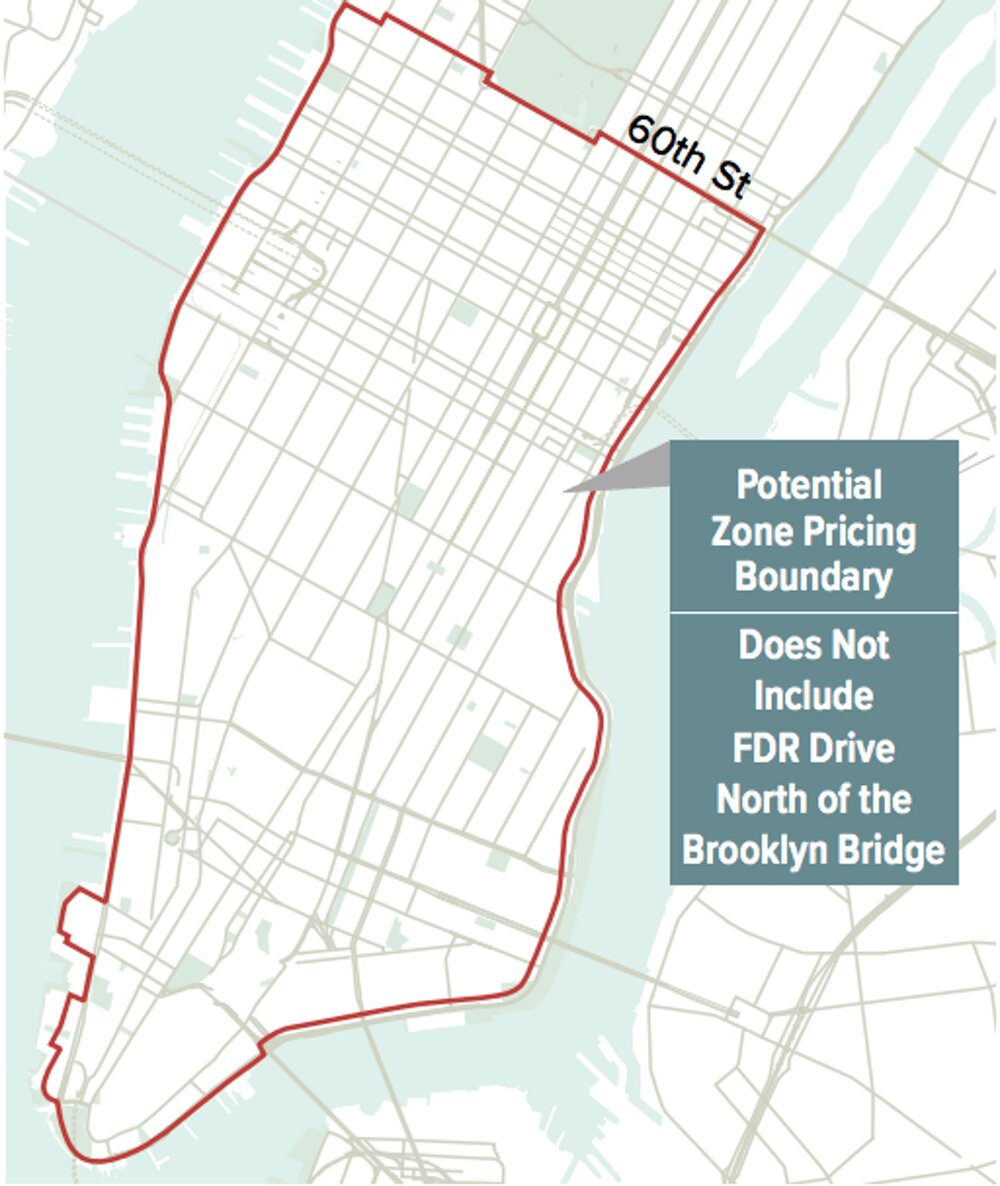

In April 2019, New York lawmakers passed a cordon congestion pricing policy for vehicles entering Manhattan below 61st Street, called the Traffic Mobility Act (TMA).

The fee is expected to raise $1 billion annually, starting in January 2021, which will go primarily towards the Metropolitan Transit Agency’s (MTA) Fast Forward plan.

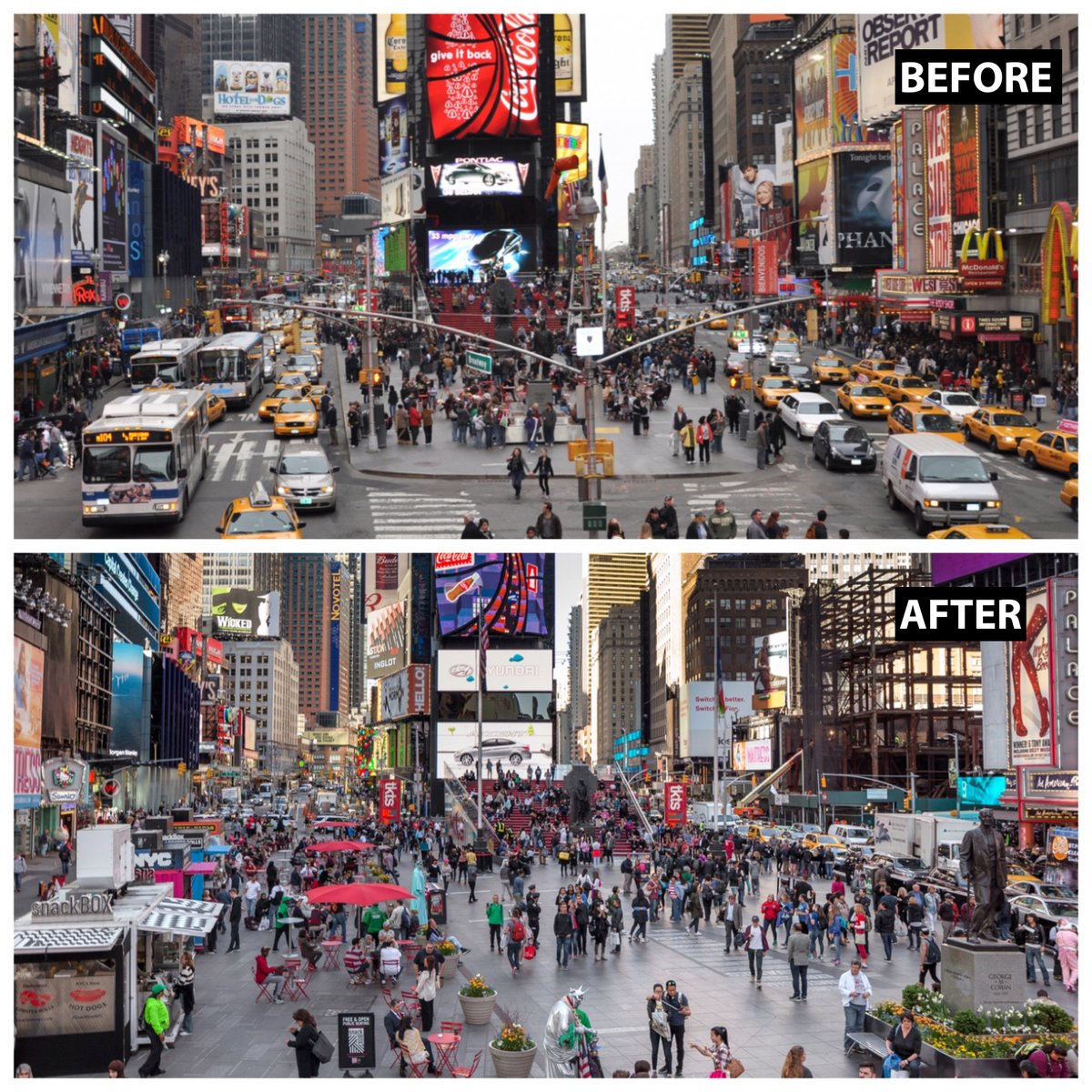

New York has led the nation on other transportation initiatives. For example, in May 2019, the city recognized the 10th anniversary of closing Broadway to vehicles and opening the street for pedestrian-only purposes.

Beyond congestion mitigation, congestion pricing benefits society as a whole by reducing fuel consumption and vehicle emissions. It also allows more efficient land use decisions, by reducing housing market distortions, and by expanding opportunities for civic participation, according to the FHWA.

Do you know how the transportation network in your community is funded?

Share this example of congestion pricing with leaders in your community.

Explore More:

Transportation & MobilityBy The Numbers

27

percent

of Latinos rely on public transit (compared to 14% of whites).