Share On Social!

Dr. Denice Cora-Bramble loves children.

From an early age, she knew that she wanted to be a pediatrician.

Her professional child-focused journey has culminated a long and successful career at Children’s National Hospital where she currently serves.

“I’ve always been intrigued by children,” Dr. Cora-Bramble said with a contagious smile. “They’re interesting little people.”

Growing up in Puerto Rico, Dr. Cora-Bramble was introduced to medicine as a child. Her aunt, who she admired greatly, was an OBGYN and one of just five females in her medical school cohort.

“She was also a mother of five,” Dr. Cora-Bramble said. “I admired how she managed being a mother and being a physician; she was a great inspiration for me from the time I was very young.”

Dr. Cora-Bramble’s parents were inspirational, too. Her mother, an African American social worker, and her father, a Puerto Rican engineer, both encouraged Dr. Cora-Bramble to do well in school.

Dr. Cora-Bramble grew up in a bilingual household, speaking English to her mother and Spanish to her father.

“Being bilingual was necessary in our household to be able to communicate with both parents,” she said.

Going to the Mainland

By the time she finished high school, Dr. Cora Bramble knew she was destined to become a pediatrician.

She started college at The George Washington University in Washington, D.C., at just age 16, where she first experienced being away from Puerto Rico and her family for extended periods of time.

“I cried my entire first year,” she said.

Luckily, the demands of academics and her job as a switchboard operator for her dorm complex and at the National Institutes of Health kept her busy.

She majored in zoology and took pre-med classes in preparation for a career as a pediatrician.

While she did well academically, college was still a struggle.

“It was just really, really tough on multiple fronts,” Dr. Cora-Bramble explained. “First, I was very young and naïve. The other thing was that there was a language [challenge]. I didn’t have an accent, so people just assumed that I was fluent in English or that it was my primary language. However, I was not completely proficient in English, especially when it came to writing.”

This language issue would prove challenging.

“I remember that in some courses, I would listen to what the professor had to say in English, and then I would take notes in Spanish. So, just imagine all the mental gymnastics that you must go through to do that – but I needed to be able to understand my notes,” Dr. Cora-Bramble said.

Saved by the Dean

Medical school was arduous, too.

After graduating with her undergraduate degree at age 20, Dr. Cora-Bramble set her sights on Howard University, a leading university in Washington, D.C., where both her parents and mentor aunt attended.

There, she attended medical school on a National Health Service Corps scholarship and spent most days attending class from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m.

All other time was spent studying – and she grew to hate this lifestyle.

“At one point I said, ‘I’m not doing this anymore. I’m quitting,’” she said.

Dr. Cora-Bramble put her foot down and stopped going to class.

“I felt as though medicine had taken over my life and that I didn’t have a life other than being a medical student.”

Dr. Cora-Bramble’s strike lasted about two weeks before the dean of Howard’s medical school called her into his office.

“He asked me, ‘Why did you stop coming to class? Are you failing in your courses?’ I said, ‘No, I’m not failing, but this is not for me. I don’t want to devote my entire life to studying,’” Dr. Cora-Bramble recalled.

By the end of their conversation, the dean had convinced her to come back to class.

“That’s why going to a school that is nurturing is so important. If that dean hadn’t called me into his office, I’m not sure what it would have happened,” Dr. Cora-Bramble explained. “It goes to show you the importance of having mentors that can support you when the going gets tough.”

Giving Back to the Community

Upon graduation from medical school, Dr. Cora-Bramble worked in school health in several areas in Washington, D.C. These areas encompassed a wide population, including many Latinos.

In her job as a school physician, she crisscrossed the city providing care to children and adolescents.

Although she was only required to serve in this role for three years as part of her National Health Service Corps scholarship obligations, she stayed for 11 years.

One of her primary responsibilities was precepting medical students completing their third-year psychiatry clerkship. These medical students would come to local schools to teach sex education to 5th and 6th grade students.

“I was the person that taught them how to do that,” Dr. Cora-Bramble explained.

During these interactions with local medical school students, Dr. Cora-Bramble was struck by the many backgrounds between some elementary school students and medical students. She realized early on that many medical students could benefit from training in care that considers people’s backgrounds.

“So, I started developing [a curriculum that incorporated people’s backgrounds] for medical students at a time when there were very few available. I was somewhat of a pioneer,” Dr. Cora-Bramble said.

This curriculum became valuable at medical schools nationwide and eventually contributed to Dr. Cora-Bramble being recruited to work at The George Washington University Medical Center in several leadership roles, including the Director of the Division of Community Health.

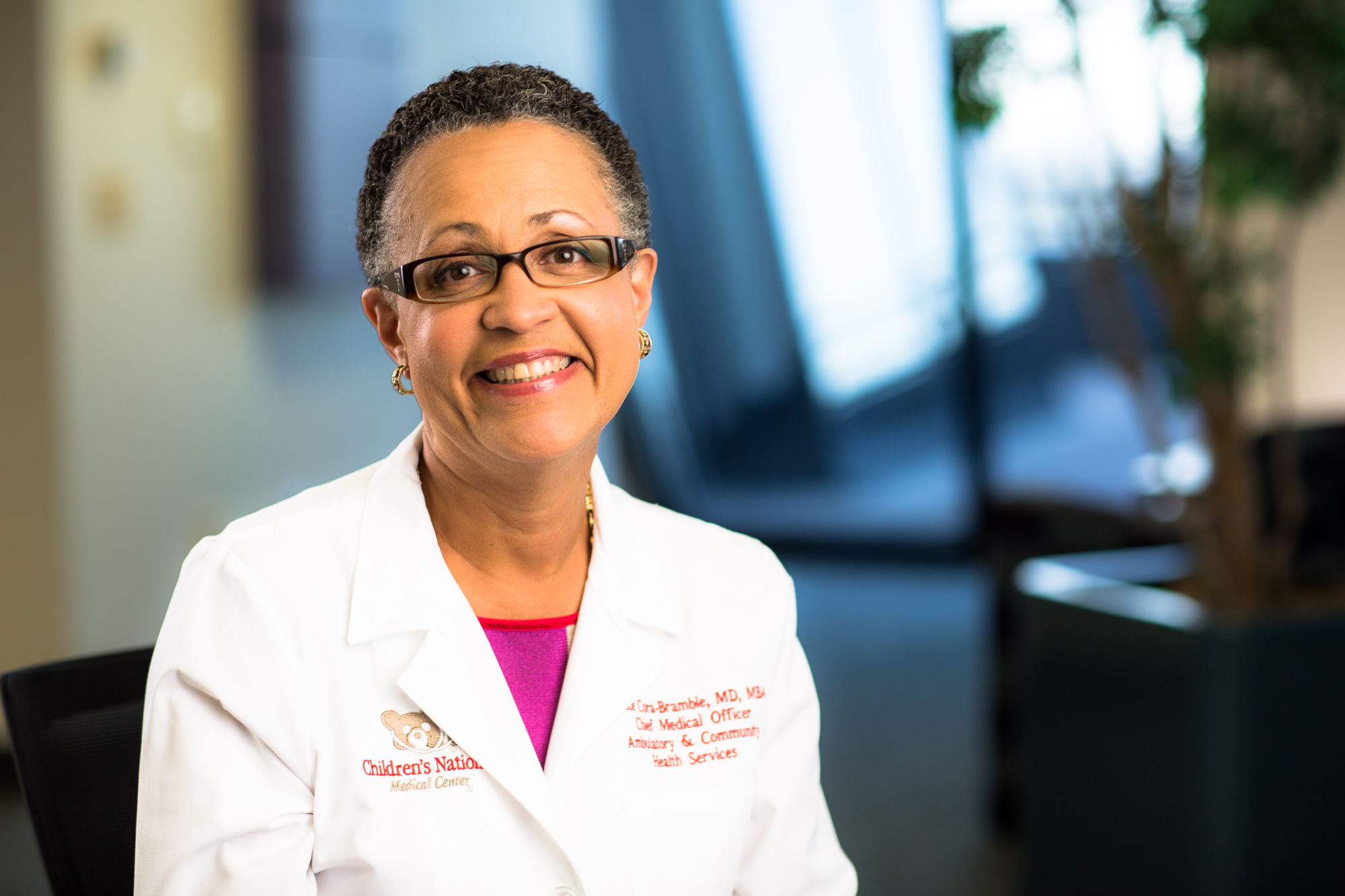

She later dedicated her skills to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services before being recruited as Senior Vice President of the Goldberg Center for Community Pediatric Health at Children’s National Hospital – marking the beginning of her 21-year career at Children’s National.

She would quickly climb the leadership ladder and become the first female and Afro-Latina to hold a chief medical officer position in the 153-year history of Children’s National – an accomplishment Dr. Cora-Bramble describes as special.

After eight years of serving as chief medical officer overseeing community and primary care initiatives, Dr. Cora-Bramble felt a calling to step back and spend more time with her family.

This new phase in life involved working part-time with Children’s National Hospital.

Leading Children’s National’s Initiatives

With Children’s National, Dr. Cora-Bramble is leading nine subcommittees dedicated to ensuring healthcare workers of all backgrounds feel supported in the workplace. They also are ensuring that all patients get high-quality care.

Dr. Cora-Bramble leads these subcommittees through data-driven evidence and measurable outcomes.

“We are one of the few children’s hospitals to take this data-driven approach to change, and we’re hopeful that sharing our successes and challenges will help others who are on a similar path,” Dr. Cora-Bramble wrote in Children’s National’s 2022-2023 Annual Report.

“It’s extremely important that we that we have [healthcare workers of all backgrounds],” Dr. Cora-Bramble said. “Published data shows that [this] positively impacts patient health outcomes.”

Family First

Although Dr. Cora-Bramble feels that she’s “been to the mountain top” of her career, her greatest accomplishment is being a mother, a grandmother, and a wife.

“To be very honest, if I were to look at everything that I’ve done in my career and in my life, that to me is the most significant,” she said.

Dr. Cora-Bramble and her husband have been married for 47 years, have three successful children (a pediatrician, businessman, and a lawyer), and five beautiful grandchildren.

By The Numbers

3

Big Excuses

people use to justify discriminatory behavior

This success story was produced by Salud America! with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The stories are intended for educational and informative purposes. References to specific policymakers, individuals, schools, policies, or companies have been included solely to advance these purposes and do not constitute an endorsement, sponsorship, or recommendation. Stories are based on and told by real community members and are the opinions and views of the individuals whose stories are told. Organization and activities described were not supported by Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and do not necessarily represent the views of Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.