Share On Social!

Alicia Gonzalez, a young leader with experience in community development, was eager to keep kids stay active, given the rise of local obesity. She partnered up with a local family foundation who wanted to start a running program.

The result was Chicago Run, a non-profit incentive based program which has promoted running to over 13,000 children.

The Need for More Physical Activity for Children

Awareness: Chicago resident Alicia Gonzalez enjoys improving the quality of life in her community.

She has experience teaching youth about AIDS, mentoring kids in Boston, and building private-sector partnerships to better people’s lives through asset-based community development (ABCD)—an approach to community development that emphasizes a community’s assets rather than its deficits.

Several years ago, she was mentoring a group of teenagers.

As Gonzalez waited outside with the group, she noticed these girls were glued to their cell phones. She decided to ask them to do something active as they waited—she asked them to run.

She had an epiphany: girls need more physical activity throughout the day, and running was the answer.

Learn: To explore how to start an organization for running, Gonzalez started speaking to her private-sector contacts and searched the Internet for obesity-prevention organizations.

At the time, 34.9% of children in Illinois were overweight, according to a Medill School news report.

A Google search on obesity prevention in Chicago led her to the Consortium to Lower Obesity in Chicago Children (CLOCC)—a multi-sector, multi-level organization that works to prevent obesity in Chicago children.

“I found out about CLOCC and reached out to the executive director, Adam Becker,” Gonzalez said. “I said to him, ‘I’m really interested in starting a running organization.’ So he told me to start coming to CLOCC’s monthly meetings.”

Gonzalez started attending some of CLOCC’s meetings.

At one meeting, she learned that The Pritzker Traubert Family Foundation—a private foundation that invests in the health and education of Chicago’s children—wanted to support obesity prevention by starting a running program.

“It was like fate,” said Gonzalez.

Frame Issue: So Gonzalez decided to contact and meet with foundation leaders to learn how she could get involved. She learned they wanted to pilot an existing running program (The New York Road Runners: Mighty Milers Program) in Chicago schools.

Gonzalez started to envision a running program that could get thousands of kids running and also incorporate activities to expose kids to the city’s history and uniqueness.

“I wanted to build a bridge between kids from all backgrounds” Gonzales said.

The foundation, recognizing Gonzalez’ strong desire to get kids moving, hired her to lead their new initiative to get kids running.

In December 2007, the non-profit organization Chicago Run was born, with Gonzalez as executive director.

Developing Chicago Run for More Physical Activity for Children

Education: At first, Gonzalez met with and presented plans for a pilot running program to the school board for Chicago Public Schools (CPS), one of the nation’s largest school districts.

She explained that Chicago Run wanted to launch a free program to promote more moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) among elementary school children, particularly for those with no access to after-school physical activity programs. Participating teachers would be offered a small annual stipend.

The school board expressed interest, given their increasing concern about local obesity rates.

They gave Gonzalez a list of 12 CPS schools at which to pilot the running program.

Mobilization: Gonzalez faced some logistical challenges.

At the time, CPS did not have a health and wellness department and Chicago Run was just starting out, so Gonzalez had to organize the pilot program from her laptop at a Panera Bread restaurant.

She contacted the 12 school principals and informed them of Chicago Run’s plans to train CPS teachers to implement the Chicago Run program over a period of 10 weeks in their schools. All it would take was the willingness of teachers to get children to run at least 15 minutes, three to five times a week.

The personal relationships she was building at each school helped set up the program. Each school was assigned a Chicago Run site coordinator, to oversee implementation, and a teacher to serve as the school’s session leader (for the pilot program, about 83% of these teachers were school P.E. coaches).

“We worked directly in the schools, that’s what I thought was going to work best in Chicago,” Gonzalez said.

Debate: After 10 weeks of working together with CPS schools, Chicago Run gained positive reviews from teachers, students and school principals. Chicago Run leaders met to discuss how to expand and improve the program. They decided to tailor the program to Chicago kids and draw on community support to make the program sustainable.

“I said to my board: ‘I believe that technology is a leading cause of childhood obesity, and it’s not going away,’” Gonzalez said.

But the group also believed that they could use technology to their advantage.

One of the ideas that had previously been discussed was building a figurative bridge for runners across the city.

What if they could use technology to unite children and get them excited about running?

Enacting a Change for Chicago Run for More Physical Activity for Children

Activation: To help teachers promote the running program, Chicago Run provided each school with:

• announcement flyers to post at school;

• posters to track class or group progress;

• a stopwatch and measuring wheel;

• cones to mark running courses; and

• incentive awards to inspire students to keep running

Once school session leaders (teachers) were selected, they were taught how to keep track of the mileage run by students during a 2-hour training session. The school’s session leader was also provided with a $500 stipend to implement the program.

Site coordinators worked with school session leaders to determine running location and other logistics.

Coordinators also worked to develop a base of community support.

Gonzalez and her team garnered donations from local businesses, banks, and other organizations to supply program incentives and provide transportation to running events for participating children.

“I took this model of asset-based community development to move forward with community organization,” Gonzalez said. “We do not work in a silo…I believe heavily in partnerships.”

Frame: The program aims to get children into the habit of running 15 minutes every day. Each school would start by getting kids to do 15 minutes of physical activity three to five times a week.

Because each school had different needs and schedules, teachers could offer the program to students during recess, class, or during P.E. time.

Incentives—water bottles, T-shirts, hats, medals, and trophies—would be awarded to participating students who reached a cumulative total of 5, 10, 15, 20, 26.2, 35, 52.4, 75, 100, and 150 miles.

Near the end of the semester, each Chicago Run school would be invited to participate in a 1-mile fun run. Buses would take participating students to a designated location where all Chicago Run students could gather for the fun run.

Change: The 10-week pilot period ended in Spring 2008.

All 12 participating pilot schools then formally instituted the Chicago Run program going forward.

Teachers reported many benefits from the program, including:

• greater school-wide unity;

• improved student behavior and attention span in the classroom;

• improved student attendance and learning potential;

• improved student/teacher relationships; and

• improved quality of recess.

Since the trial period, Chicago Run has reached more than 13,000 students in 45 public schools, from 31 communities!

The group also launched an online mileage tracker in 2012.

Sustaining Chicago Run for More Physical Activity for Children

Implementation: How did the program take off?

“We never have never really had to do any marketing, most people learn about Chicago Run by word of mouth. We have teachers that have brought the program to new schools,” Gonzalez said.

Take, for example, Joseph Jungman Elementary School and P.E. coach Lori Klein-Blazek.

This predominantly Latino school is located near the lower west-side of Chicago in the Pilsen and Little Village districts.

At Jungman, which was not an original pilot school, Lori Klein-Blazek learned about it from a fellow P.E. coach.

Klein-Blazek said she’s always searching for free programs and resources to keep her students active.

“I have a zero budget for health so when I heard about the program, I called and said, ‘I’m interested in getting involved,’” Klein-Blazek said.

Because the demand was so great and funding was limited, program organizers originally considered turning down Klein-Blazek’s request to bring Chicago Run to her school.

Klein-Blazek told them: “If you take me and my school on, I promise you will not be disappointed.”

Sure enough, Klein-Blazek proved that her students were serious about running. During the first season of Chicago Run at Jungman, two groups completed 100 miles of running. Klein-Blazek said her school brings 50-100 students to the end-of-semester Fall and Spring Fun Runs.

“I have noticed the kids are more excited…they say, ‘OK, are we running?’…they are enjoying it,” she said.

Klein-Blazek adds that implementing the program is easy. It doesn’t require equipment and it only takes 15 minutes of the school day. When it’s time to run, Klein-Blazek encourages her students to run an additional lap by having them jump to give her a high-five. She also sets up foam noodles for the kids to jump over and has the younger kids hold onto items, such as a baton or a small pouch filled with beans.

“[The kindergarteners] love to hold on to something while they run,” Klein-Blazek said.

Parents and family members also go to the Fun Run to support their child, and many even end up running with the students, Klein-Blazek said.

Chicago Run leaders, meanwhile, continue to improve the program with technology.

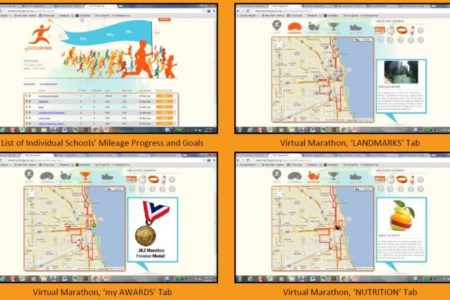

They developed My Chicago Run, an online portal that serves as a mileage tracker and a learning tool to teach kids about Chicago’s important landmarks and rich background.

Students and teachers can log in, set running goals, track their progress on virtual maps, view important landmarks, view nutrition facts, see what prizes they have won, and view a log that displays their activity.

It essentially takes kids on a virtual journey through neighborhoods across Chicago, Gonzalez said

CPS officials continue to expand their efforts to increase student health.

Officials are working to bring running opportunities to middle-school students through the Running Mates program, where students gather from different schools to train together. They meet three to five times a week before or after school.

“I reached out to Nike at the time and asked if they would be interested in sponsoring something like this,” Gonzalez said. “I told them that it would get them [kids] to run a race and build relationships that might not otherwise exist. At first we had two schools that trained together. Now there are about 11 schools and 225 kids participating.”

Sustainability:Chicago Run has created additional materials—an indoor fitness CD, fitness DVDs and worksheets—to provide teachers with even more ways to keep their students active throughout the day.

“Over the years we’ve gone from just running to yoga, and indoor fitness,” Gonzalez said. “We’ve also helped with the establishment of wellness committees…because that’s what they [schools] want.”

Chicago Run continues to rely on corporate sponsors, fundraising, charity runners, and volunteers to sustain its activities. That’s not to mention their school partners.

But if they’re anything like Klein-Blazek, Chicago Run will be around a long time.

“As long as I’m here, I’m going to keep doing it because I think it’s really beneficial,” Klein-Blazek said.

By The Numbers

33

percent

of Latinos live within walking distance (<1 mile) of a park

This success story was produced by Salud America! with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The stories are intended for educational and informative purposes. References to specific policymakers, individuals, schools, policies, or companies have been included solely to advance these purposes and do not constitute an endorsement, sponsorship, or recommendation. Stories are based on and told by real community members and are the opinions and views of the individuals whose stories are told. Organization and activities described were not supported by Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and do not necessarily represent the views of Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.