Share On Social!

At the end of her life, Samarys Seguinot-Medina hopes to say she made the world a safer place to live for the children in her family.

Seguinot-Medina has known two personal truths since she was young: Nature, as well as humanity, are worth fighting for; and there are countless issues to battle — causing her to devote her time, career to promoting environmental justice and chemical safety.

That is why, for almost 10 years, Seguinot-Medina and her colleagues at Alaska Community Action on Toxics (ACAT) worked to ban hazardous flame-retardant chemicals, or polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), in Alaska (8.9% Latino).

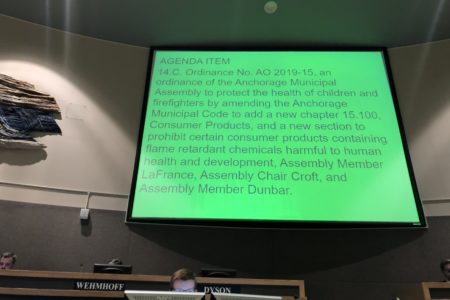

Those efforts eventually resulted in passing Assembly Ordinance 2019-15(S), or the Toxic Free Children Ordinance, an Anchorage-wide ban of products containing those substances.

“I know that environmental health and justice work, more so when you work with chemicals, is kind of a dry subject,” Seguinot-Medina said. “Talking about cancer, chemicals, and pollution, it’s not the most positive subject. It is difficult to ‘sell’ and engage people… But I understood there was a bigger need in this field.”

Puerto Rico, Childhood, and Early Activism

For Seguinot-Medina, environmentalism began in her hometown — San Sebastián, Puerto Rico (97% Latino).

She notes her love of the earth, like her last name, comes from both sides of her family.

“My mom comes from a very humble community of my town, with many communities of color and people living in poverty,” Seguinot-Medina said. “You are very close to nature. You have to grow your food. You have to do a lot of things that are directly in contact with and dependent on nature.

“My father and his father were workers in the sugar cane mill industry. So, my playground was the sugar cane mills and the bamboo forest. I was born with a connection to nature and was intrigued by how things work in nature. I noticed how dependent we are on it, as humans to live, survive, and thrive.”

Seguinot-Medina would go on to study at some of the island’s best institutions, all the while participating in environmental engagement.

Working with other activists, she helped found the first Latino Sierra Club chapter.

That club would go on to save some of the island’s forests from destructing for hotel development.

Still, Seguinot-Medina hoped to see the world and continue her activism elsewhere.

“I always had this dream, to come to Alaska to see the northern lights,” Seguinot-Medina said.

Chemicals, Cancer, and Civil Servants

Seguinot-Medina’s work with ACAT began during her time in school when she interned with the group as a part of her studies. She later moved to Alaska permanently in 2009, after graduating from the University of Puerto Rico with her doctorate in public and environmental health.

She now serves as ACAT’s Environmental Health Program Director.

It was there she saw firsthand the impacts PBDEs make on those who are exposed, especially among firefighters — it is the primary cause of fatalities among that group, according to The International Association of Firefighters.

However, their cancer development isn’t triggered by smoke inhalation.

Instead, the chemicals these public servants are exposed to on the job trigger the illnesses. Seguinot-Medina said these stories drive her work.

“You have cancer, knowing what you are putting your family through,” Seguinot-Medina said. “Then on top of that you [were] risking your life, knowing there are chemicals you are exposed to because that’s part of your job.”

These chemicals are an issue nationally, affecting a wide variety of people — including families that have certain furniture in their homes.

The group of chemicals came into the public consciousness in the 1970s when researchers discovered that children were absorbing the chemical’s toxicity through their pajamas. That finding led to a nation-wide ban of its use in children’s clothing.

Since that time, PBDEs reportedly continue to cause harm to those who face exposure through several avenues.

The firefighters’ stories and information her group, Alaska Community Action on Toxics (ACAT), already knew about these chemicals prompted Seguinot-Medina and her coworkers to begin taking action in PBDE regulation reform.

Hard Work, Failure, and Success

ACAT’s first goal aimed to have Alaska’s state legislators pass state-wide PBDE regulation.

However, chemical manufacturing companies and their lobbyists stopped any forward momentum the group made, according to Seguinot-Medina.

One of the chemical lobby’s initial supporters was Dr. David Heimbach, according to Seguinot-Medina. Once a Seattle burn surgeon, Heimbach was tapped as a witness to speak to government bodies on behalf of manufactures.

“In this case, [they used] ‘fake science’ to convince legislators,” Seguinot-Medina said. “[Dr. Heimbach] was paid by the chemical industry and lied, under oath, about the safety of these chemicals. He was even making up stories about children being burned in fires. That didn’t even happen.”

Heimbach would eventually give up his medical license to avoid more significant consequences, according to the Chicago Tribune.

Despite ACAT’s efforts to correct the misinformation, legislators would not move forward with any regulation. Seguinot-Medina and her colleagues then decided to refocus their efforts by shifting PBDE initiatives to local communities, including Anchorage.

The group’s activism plan to pass the ordinance was layered and targeted several groups.

- Outreach and Advocacy: ACAT met with various organizations, such as the city’s fire fighter’s union and nurses association, to garner support from members of the Anchorage community.

- Online Campaign: The group used social media, email blasts, and press coverage to inform anchorage citizens about the issues at hand.

- Meeting with Assembly Members: They established relationships with legislators through personal meetings and phone calls to keep this issue on the forefront of the conversation.

- Setting up Events: Community events, such as One Course Discourse, allowed citizen to participate in the issue, get informed, and take action in keeping their families safe.

- Letters of Support: ACAT submitted letters.

- Presentations: Seguinot-Medina and her coworkers presented their findings to community councils and the Anchorage Chamber to garner further support.

- Business Plan: The group met with businesses to form strategies to ensure any new regulation would not severely impact commerce.

Their multi-faceted approach led to dialogue, information reaching the right people, and members of the Anchorage community stepping up to fight for PBDE regulation, according to Seguinot-Medina.

On March 19, 2019, the Assembly unanimously approved the ordinance.

The ordinance prohibits products containing PBDEs from being sold in the city to protect overall human health, and it is one of the most substantial pieces of anti-flame retardant legislation, according to the Anchorage Press.

While ACAT was thrilled about the victory, Seguinot-Medina said their dedicated efforts made it easy to believe the ordinance would pass.

“I was so excited, but I wasn’t so surprised,” Seguinot-Medina said. “We did a good job of getting organized and supporting people so they could use their voice to give their testimony. We have the science to back up everything we said, and everything those great people said in their statements.

“It was a matter of time. We had been fighting for this for a long time and working toward this making Anchorage a safer and more just place for people to live in.”

Progress, Perspective, and Hope

When the Toxic Free Children Ordinance passed, Seguinot-Medina was in Puerto Rico helping her mother through cancer treatment.

She did, however, phone in to celebrate with her colleagues.

“It gives you hope,” Seguinot-Medina said. “It’s hard work, and it’s not always positive. It’s a small victory, but it’s huge at the same time.”

Still, the ACAT team doesn’t plan to slow down anytime soon. Eventually, the group plans to take on the state legislator again, once they’ve done enough work in local communities.

Seguinot-Medina’s vision and work come from an internal passion for the world around her and those that inhabit it — one that harkens back to her days exploring Puerto Rico’s countryside.

“It’s my passion, my calling. I feel like I have the opportunity to do something about it,” Seguinot-Medina said. “Engaging other people. Telling them, they have a voice, especially minority groups, who are the most vulnerable, and for the youth and the children. I think it’s fair that we do everything we can now, so they can have a chance of experiencing life like I did when I was little in the sugar cane mills; going to the river and playing in the bamboo forest.”

For most environmentalists, the work is never really complete, rather a continual struggle — one that is on the clock, according to Seguinot-Medina.

“I see the changes happening so fast,” Seguinot-Medina said. “Realizing all the work that needs to be done — I want to be sure when my niece asks me, ‘Titi, what do you do to make this world a better place?’ I can say, ‘I did something. I tried. I did my best.’ That’s why I’m in this field.”

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a collaboration between Salud America! and the Hoffman Toxicant-Induced Loss of Tolerance (TILT) program at UT Health- San Antonio. To find out if you are TILTed due to exposure to everyday foods, chemicals, or drugs, take a self-assessment or learn more about TILT.

Explore More:

Chemical & Toxic ExposureBy The Numbers

1

Quick Survey

Can help you find out how chemically sensitive you are

This success story was produced by Salud America! with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The stories are intended for educational and informative purposes. References to specific policymakers, individuals, schools, policies, or companies have been included solely to advance these purposes and do not constitute an endorsement, sponsorship, or recommendation. Stories are based on and told by real community members and are the opinions and views of the individuals whose stories are told. Organization and activities described were not supported by Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and do not necessarily represent the views of Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.