Share On Social!

This is part of our Latina Mom and Baby Health: A Research Review »

Benefits of breastfeeding

The benefits of breastfeeding for both mother and baby are well established in the literature, and yet breastfeeding rates in the United States remain below desired levels.38,39

According to recommendations from The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), mothers should exclusively breastfeed their infants for at least the first 6 months of life, with continuation for 1 year or longer. In addition, breastfeeding infants should not receive supplemental formula unless advised by a health care professional.39,40

As part of the Healthy People 2020 initiative, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services outlined several goals relating to breastfeeding, which include:

- 81.9 percent of new mothers initiating breastfeeding;

- 60.6 percent continuing for at least 6 months; and

- 34.1 percent continuing to 1 year postpartum.41,42

- For exclusive breastfeeding, the goals were 46.2 percent at 3 months and 25.5 percent at 6 months.41

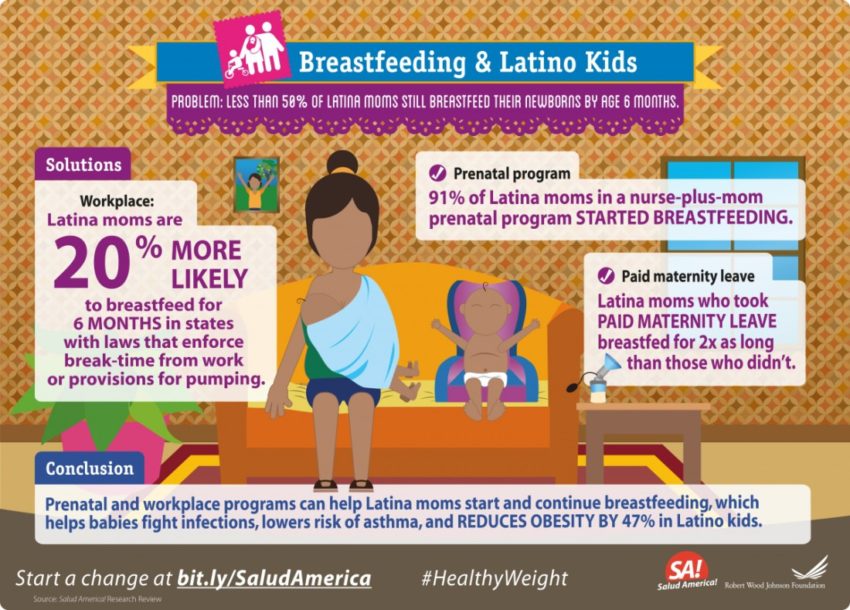

In the Latino community, these goals are supported by recent findings that breastfeeding duration can positively impact childhood obesity in Latino youths. In 2012, staff from the Los Angeles County WIC program conducted phone surveys with caregivers of 1,483 Latino children (ages 2-4). The study demonstrated that breastfeeding for 1 year or more can profoundly lower the prevalence of obesity among this population.43

In 2014, the same group published findings from phone surveys with caregivers of 2,295 low-income, primarily Latino children. This study confirmed the previous finding, demonstrating that breastfeeding ≥12 months resulted in a 47 percent reduction in obesity prevalence.44 Another study published in 2014 confirmed that breastfeeding for more than 1 year significantly protected Latino children from developing early childhood obesity in a cohort of high-risk, recently immigrated Latina women in San Fransisco.45 In fact, the protective effect of breastfeeding on obesity seen in this study persisted through age 4.45

Latina breastfeeding duration an issue

Although Latina mothers are nearing the Healthy People 2020 target for breastfeeding initiation, their rates of continued and exclusive breastfeeding remain considerably under the 2020 goals.46

In addition, Latina mothers may be more likely to provide early formula supplementation compared with mothers of other racial or ethnic backgrounds.46 Compared with non-Latino white mothers, Latina women are also more likely to introduce solids before 4 months of age, more commonly utilize restrictive feeding practices (such as pressuring their children to eat more food, limiting overall intake, or restricting the intake of certain foods), and demonstrate a reduced rate of exclusive breastfeeding.10

Evidence suggests that factors such as nonexclusive breastfeeding and early formula supplementation both contribute to significantly higher body mass indexes (BMIs) in Latino children.47

Taken together, these data suggest that increasing breastfeeding continuation and exclusivity among Latina mothers may help to lower the burden of childhood obesity in Latino youths.

Several barriers may contribute to low rates of continued and exclusive breastfeeding in this population. For instance, Latina mothers have some of the highest overweight and obesity rates compared with other racial or ethnic groups, and pre-pregnancy weights have been associated with lower rates of breastfeeding.48

In addition, many Latina mothers are low-income, WIC participants, which is another reported risk factor for lower breastfeeding rates, especially among Latina women.48,49 In fact, as WIC provides access to free infant formula, program participation itself may be a disincentive for breastfeeding.48,49

Pain/discomfort, embarrassment, employment, and inconvenience are other commonly reported barriers to breastfeeding for new mothers.48 For minorities, additional cultural, social, economic, political, and psychosocial factors may also confound a mother’s decision to breastfeed. Minority-specific barriers may include a lack of maternal access to breastfeeding information and support, acculturation, language, and literacy.48

Policy changes can help mothers who choose to breastfeed

While interventions, such as peer counseling, have been shown to make a positive affect on breastfeeding rates among Latina mothers,46,48,50–52 additional policy measures may be necessary to help optimize breastfeeding practices among this population.

There are several policy-related areas that may promote breastfeeding among Latina mothers. This may include policies directed at improving breastfeeding support in hospitals and childcare settings, in the workplace, in public areas, as well as in educational systems for adolescent mothers.

Regulations surrounding health insurance and paid maternity leave may also play a supportive role. In 2011, the Surgeon General issued a Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding, which outlined a number of measures important for increasing societal support and encouraging breastfeeding rates to grow.53

Breastfeeding support in hospitals

Policies improving breastfeeding support in the hospital setting are particularly critical for Latina mothers, as Latina women commonly indicated that they were not properly instructed on how to breastfeed by hospital staff.54

This marks an important area for improvement as hospitals and birth centers play an essential role in encouraging breastfeeding initiation following childbirth. Several organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the World Health Organization (WHO)/United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), have outlined guidelines for establishing a hospital policy that supports breastfeeding.38,55,56

In fact, the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding jointly issued by WHO and UNICEF has been shown to increase breastfeeding initiation, duration, and exclusivity when properly incorporated.55,57,58 The 10 steps outlined include measures to better inform pregnant women about the benefits of breastfeeding, help mothers to initiate breastfeeding in the first hour after birth, eliminate other feeding practices unless medically necessary, allow the infant to remain in the room with the mother after birth (referred to as “rooming-in”), avoid pacifiers, and place mothers in contact with breastfeeding support groups on hospital discharge.56

Importantly, in the National Survey of Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has determined that only 37 percent of birth centers practice more than five of 10 steps outlined by WHO/UNICEF, with only 2.5 percent practicing nine of 10 steps.59

Out of all hospitals surveyed, 58 percent incorrectly advised mothers to limit suckling time at the breast, 41 percent offered pacifiers improperly, 30 percent supplemented more than half of all newborns with commercial infant formula, 66 percent provided mothers with discharge packs containing infant formula samples, and only 14 percent and 27 percent, respectively, had hospital policies in place and provided breastfeeding support after discharge.59,60

The AAP responded to these findings by declaring the need for a “major conceptual change” in hospital services for mothers and their infants; they outlined several recommendations on breastfeeding management for healthy term infants.39

Similar to the 10 steps outlined by WHO/UNICEF, the AAP policies for optimizing breastfeeding include: encouraging direct skin-to-skin contact during feedings, delaying routine post-delivery procedures until after the first feeding, formally evaluating breastfeeding by trained caregivers, removing supplementation with commercial formula or other fluids unless medically indicated, and discontinuing practices that limit the time an infant can spend with the mother, limit feeding duration, or provide unlimited pacifier use.39

Breastfeeding support in the workplace

As an unsupportive workplace environment can greatly affect avoidance or discontinuation of breastfeeding among working mothers.

Policies intending to encourage and protect women breastfeeding in the workplace are also desirable.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) signed into law in March of 2010 included an amendment to Section 7 of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), known as the Reasonable Break Time for Nursing Mothers Provision.61 This amendment requires employers to provide mothers with reasonable break time to express, or pump, breast milk for 1 year postpartum.61 According to the provision, employers must also provide a location for mothers to express breast milk that is not a bathroom, is shielded from view, and is free from intrusion from other coworkers and the public.61

In 2015, a cross-sectional survey was performed to evaluate lactation support in the workplace by New Jersey employers, after implementation of the federal Reasonable Break Time for Nursing Mothers amendment.62 The study compared amenity scores with regard to the furnishings, pump availability, milk storage options, and other amenities of employer provided lactation rooms.

Overall, the mean amenity score of employer-provided lactation rooms in New Jersey remained far below comprehensive (0.95 out of a maximum score of 3.0), with nearly half of all employers surveyed documenting no amenities for the lactation room. Hospitals were more likely than nonhospital employers to provide lactation rooms, have a company-wide breastfeeding policy, and provide breastfeeding support in the form of educational classes or resources. Among nonhospitals, only 36 percent offered lactation rooms and only 7.7 percent had breastfeeding policies in place. In addition, of nonhospital organizations, 61.6 percent demonstrated no awareness of the federal Reasonable Break Time law.62

These findings indicate that, despite laws promoting breastfeeding in the workplace, additional efforts need to be made to increase awareness of federal mandates, understand barriers to compliance, and outline strategies that may help employers to implement a breastfeeding-friendly atmosphere.

In a publication by Smith-Gagen and colleagues in 2013, 8 additional state laws were outlined that aimed to encourage breastfeeding at the state level, in both work and public settings.63

This included legislation designed to exempt breastfeeding from public indecency laws, allow women to breastfeed in any public or private location, exempt breastfeeding mothers from jury duty, promote breastfeeding awareness education campaigns, require reasonable unpaid break-time from work to express breast milk, and require a private and sanitary location for mothers to express breast milk.63,64

Enforcement provisions were also directed at enforcing workplace pumping and public breastfeeding laws.63 Interestingly, this study found that, relative to non-Latino whites, Mexican American women were 30 percent more likely to meet the AAP’s recommendation of breastfeeding for at least 6 months in states with laws that provided break-time from work.63 Mexican American mothers were also 20 percent more likely to breastfeed for at least 6 months in regions with enforcement provisions for pumping laws.63

These findings suggest that legislation supporting breastfeeding in the workplace may be beneficial in achieving breastfeeding goals in Latino populations.

Presently, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 27 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico have passed laws relating to breastfeeding in the workplace.64 Additionally, 17 states and Puerto Rico have exempted (or postponed) breastfeeding mothers from jury duty.

Regarding breastfeeding in public, 49 states, the District of Columbia, and the Virgin Islands currently have laws that specifically allow breastfeeding to occur in any public or private location. Breastfeeding is also exempted from public indecency laws in 29 states, the District of Columbia, and the Virgin Islands. In the state of New York, a Breastfeeding Mothers Bill of Rights is required to be posted in all healthcare facilities providing maternal care.64

Breastfeeding support in childcare settings

In addition to laws surrounding breastfeeding in the workplace and in public, three U.S. states have also passed laws relating to breastfeeding in a childcare setting.64

This includes Louisiana, which prohibits discrimination against breastfed babies by any childcare facility, as well as Maryland, which requires that childcare centers establish training and policies to promote breastfeeding practices.

In Mississippi, licensed childcare facilities are required to provide a sanitary place, other than a bathroom, for mothers to breastfeed their children, express breast milk, and safely store expressed milk in a refrigerator. Mississippi childcare facility staff must also be trained in the safe and proper storage and handling of human milk, and the facility is required to display breastfeeding promotional information to its clients.64

The AAP and American Public Health Association (APHA) support this movement with the recommendation that each childcare or early childhood education facility should “encourage, provide arrangements for, and support breastfeeding.”65 These organizations agree that childcare centers should require appropriate staff training, provide support for breastfeeding mothers, and offer a designated location for mothers to feed and express breast milk.65

Breastfeeding support via health insurance

In terms of policies surrounding health insurance support for breastfeeding, the ACA requires new private health insurance plans to offer preventive health services for women with no cost sharing.64

These preventive services include breastfeeding support, supplies, and lactation counseling for peripartum mothers.64 Another example of health care-related support is the potential for insurance providers to offer more flexible postpartum schedules for mothers as well as better options for paid family leave.

Young mothers may also be especially at risk for facing breastfeeding-related barriers. This is particularly relevant to the Latino population as Latino teen birth rates remain twice as high than that for non-Latino white teens; in fact, in 2013, Latino teens demonstrated the highest rate of live births among females between ages 15-19.66

Evidence from the CDC’s National Immunization Survey has shown that young mothers are less likely to initiate breastfeeding and often quit breastfeeding more quickly than older mothers.67

Teen mothers are often faced with unique barriers, such as embarrassment, lack of parenting readiness, need for peer acceptance, and dependence on social support systems that may not encourage breastfeeding.68–71

Policy updates similar to the Affordable Care Act’s Reasonable Break Time for working mothers should be extended to student mothers as well. Providing reasonable break time and a clean, private space for student mothers to express breast milk may help to encourage young women to continue breastfeeding for a longer duration.71

More from our Latina Mom and Baby Health: A Research Review »

- Introduction & Methods

- Key Research Finding: Maternal obesity

- Key Research Finding: Breastfeeding (this section)

- Key Research Finding: Breastfeeding promotion

- Key Research Finding: Marketing of infant formula

- Key Research Finding: Latino infant habits

- Key Research Finding: Early childcare settings

- Policy Implications

- Future Research Needs

References for this section »

38. Gartner LM, Morton J, Lawrence R a, et al. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2005;115(2):496-506. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-2491.

39. Eidelman AI, Schanler RJ, Johnston M, et al. Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e827-e841. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-3552.

40. American Academy of Pediatrics American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Guidelines for Perinatal Care. 7th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; and Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2012.

41. Maternal, Infant, and Child Health | Healthy People 2020. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/maternal-infant-and-child-health/objectives. Accessed June 14, 2015.

42. Breastfeeding: Data: NIS | DNPAO | CDC. http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/nis_data/. Accessed June 8, 2015.

43. Davis JN, Whaley SE, Goran MI. Effects of breastfeeding and low sugar-sweetened beverage intake on obesity prevalence in Hispanic toddlers. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(1):3-8. doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.019372.

44. Davis JN, Koleilat M, Shearrer GE, Whaley SE. Association of infant feeding and dietary intake on obesity prevalence in low-income toddlers. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22(4):1103-1111. doi:10.1002/oby.20644.

45. Verstraete SG, Heyman MB, Wojcicki JM. Breastfeeding offers protection against obesity in children of recently immigrated Latina women. J Community Health. 2014;39(3):480-486. doi:10.1007/s10900-013-9781-y.

46. Chapman DJ, Pérez-Escamilla R. Breastfeeding among minority women: moving from risk factors to interventions. Adv Nutr. 2012;3(1):95-104. doi:10.3945/an.111.001016.

47. Zhou YE, Emerson JS, Husaini BA, Hull PC. Association of infant feeding with adiposity in early childhood in a WIC sample. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2014;25(4):1542-1551. doi:10.1353/hpu.2014.0181.

48. Jones KM, Power ML, Queenan JT, Schulkin J. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med. 2015;10(4):186-196. doi:10.1089/bfm.2014.0152.

49. Sparks PJ. Racial/ethnic differences in breastfeeding duration among WIC-eligible families. Women’s Heal Issues Off Publ Jacobs Inst Women’s Heal. 2011;21(5):374-382. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2011.03.002.

50. Howell EA, Bodnar-Deren S, Balbierz A, Parides M, Bickell N. An intervention to extend breastfeeding among black and Latina mothers after delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(3):239.e1-e5. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.11.028.

51. Sandy JM, Anisfeld E, Ramirez E. Effects of a prenatal intervention on breastfeeding initiation rates in a Latina immigrant sample. J Hum Lact Off J Int Lact Consult Assoc. 2009;25(4):404-411; quiz 458-459. doi:10.1177/0890334409337308.

52. Anderson AK, Damio G, Chapman DJ, Pérez-Escamilla R. Differential response to an exclusive breastfeeding peer counseling intervention: the role of ethnicity. J Hum Lact Off J Int Lact Consult Assoc. 2007;23(1):16-23. doi:10.1177/0890334406297182.

53. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding. 2011. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/calls/breastfeeding/index.html. Accessed October 6, 2015.

54. Ogbuanu CA, Probst J, Laditka SB, Liu J, Baek J, Glover S. Reasons why women do not initiate breastfeeding: A southeastern state study. Women’s Heal Issues Off Publ Jacobs Inst Women’s Heal. 2009;19(4):268-278. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2009.03.005.

55. WHO | Protecting, promoting and supporting breast-feeding. WHO. http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/9241561300/en/. Accessed June 10, 2015.

56. WHO | Evidence for the ten steps to successful breastfeeding. WHO. http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/9241591544/en/. Accessed June 14, 2015.

57. Philipp BL, Merewood A, Miller LW, et al. Baby-friendly hospital initiative improves breastfeeding initiation rates in a US hospital setting. Pediatrics. 2001;108(3):677-681.

58. Murray EK, Ricketts S, Dellaport J. Hospital practices that increase breastfeeding duration: results from a population-based study. Birth. 2007;34(3):202-211. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.2007.00172.x.

59. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: hospital practices to support breastfeeding–United States, 2007 and 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(30):1020-1025.

60. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Breastfeeding-related maternity practices at hospitals and birth centers–United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(23):621-625.

61. U.S. Department of Labor – Wage and Hour Division (WHD) – Section 7(r) of the Fair Labor Standards Act – Break Time for Nursing Mothers Provision. http://www.dol.gov/whd/nursingmothers/Sec7rFLSA_btnm.htm. Accessed June 14, 2015.

62. Bai YK, Gaits SI, Wunderlich SM. Workplace lactation support by New Jersey employers following US Reasonable Break Time for Nursing Mothers law. J Hum Lact Off J Int Lact Consult Assoc. 2015;31(1):76-80. doi:10.1177/0890334414554620.

63. Smith-Gagen J, Hollen R, Walker M, Cook DM, Yang W. Breastfeeding laws and breastfeeding practices by race and ethnicity. Women’s Heal Issues Off Publ Jacobs Inst Women’s Heal. 2014;24(1):e11-e19. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2013.11.001.

64. Breastfeeding State Laws. http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/breastfeeding-state-laws.aspx. Accessed June 14, 2015.

65. American Academy of Pediatrics, American Public Health Association, National Resource Center for Health and Safety in Child Care and Early Education. Caring for Our Children: National Health and Safety Performance Standards; Guidelines for Early Care and Education Programs. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2011. http://cfoc.nrckids.org/. Accessed June 14, 2015.

66. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Teen Pregnancy. http://www.cdc.gov/teenpregnancy/about/index.htm. Accessed September 24, 2015.

67. National Immunization Survey, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Health and Human Services. Rates of Any and Exclusive Breastfeeding by Sociodemographics Among Children Born in 2011.; 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/nis_data/rates-any-exclusive-bf-socio-dem-2011.htm. Accessed June 14, 2015.

68. Feldman-Winter L, Shaikh U. Optimizing breastfeeding promotion and support in adolescent mothers. J Hum Lact Off J Int Lact Consult Assoc. 2007;23(4):362-367. doi:10.1177/0890334407308303.

69. Hoffman S. By the Numbers: The Public Costs of Teen Childbearing. Washington, DC: The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy

70. Diploma Attainment Among Teen Mothers. Child Trends. http://www.childtrends.org/?publications=diploma-attainment-among-teen-mothers. Accessed June 14, 2015.

71. The Next Generation of Title IX: Pregnant and Parenting Students. Natl Women’s Law Cent. 2012. http://www.nwlc.org/resource/next-generation-title-ix-pregnant-and-parenting-students. Accessed June 14, 2015.

Explore More:

Healthy Families & SchoolsBy The Numbers

142

Percent

Expected rise in Latino cancer cases in coming years