Share On Social!

This is part of the Salud America! The State of Latinos and Housing, Transportation, and Green Space: A Research Review »

Summary

U.S. Latinos report specific transportation challenges that arise due to the discrepancy between where Latinos live versus where they work. These challenges include transit fare affordability, reliability, and coverage.

Latinos Use Public Transit Frequently

According to the Pew Research Center, Americans who are lower-income, non-White, immigrants, or under 50 are most likely to use public transportation on a regular basis [39].

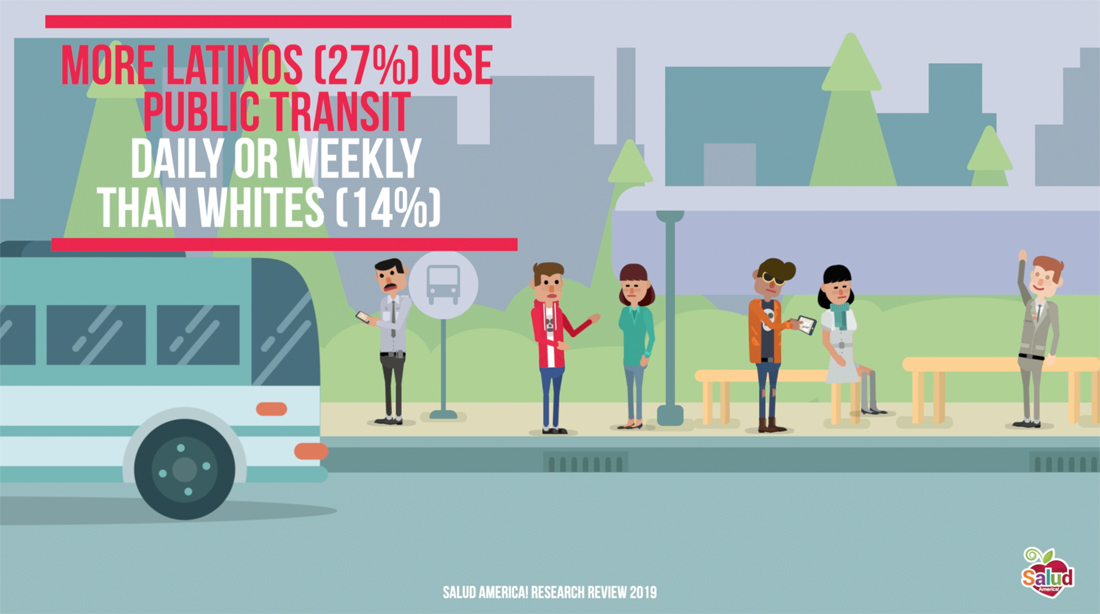

Among urban residents, 27% of Latinos use public transit daily or weekly, compared to 14% of non-Latino Whites, and foreign-born urban residents are 20% more likely to regularly use public transportation than native-born urban dwellers (38% vs 18%) [39].

Latinos and immigrants are less likely to have access to an automobile than other groups, are more likely to use public transit for commuting to work, and tend to live father away from their jobs—making walking or biking to work more challenging [40, 41].

Latinos and immigrants are less likely to have access to an automobile than other groups, are more likely to use public transit for commuting to work, and tend to live father away from their jobs—making walking or biking to work more challenging [40, 41].

Therefore, in the United States, Latinos are heavily dependent on access to public transport.

Latinos Face Long Commutes

As many low-income Latinos have been pushed into neighborhoods further from transport hubs to maintain housing affordability, the ability of these individuals to access jobs, essential services, and social networks has changed.

A trend toward the “suburbanization” of jobs has also been occurring, so that employees have to commute from their home to a suburb for work, and in the case of low-wage workers, frequently to a different suburb than the one they live [42]. It has long been known that a transit coverage gap exists between urban and suburban locales, with suburban areas generally underserved by public transit [42].

The basic implication of these coverage differences is that transit routing and job location will, along with where they live, either expand or limit an individual’s employment and transportation choices. The suburbanization of low-wage jobs, and the increasing suburbanization of low-income residents—not necessarily to the same cities and towns—means that public transit cannot provide sufficient service to pair employees and employers disbursed throughout a given region [43]. Thus, simply getting to work has become increasingly difficult for many low-income Latinos.

Unfortunately, the industries specifically employing high numbers of Latinos, including agriculture, construction, and manufacturing, have demonstrated the greatest shift to the suburbs [42]. Other jobs often employing Latinos, including landscaping, home cleaning services, and child care, are frequently located in suburbs where low-income Latinos do not commonly reside, and which have poor public transit access [9, 41]. This is also called spatial mismatch or employers and employees.

Unfortunately, the industries specifically employing high numbers of Latinos, including agriculture, construction, and manufacturing, have demonstrated the greatest shift to the suburbs [42]. Other jobs often employing Latinos, including landscaping, home cleaning services, and child care, are frequently located in suburbs where low-income Latinos do not commonly reside, and which have poor public transit access [9, 41]. This is also called spatial mismatch or employers and employees.

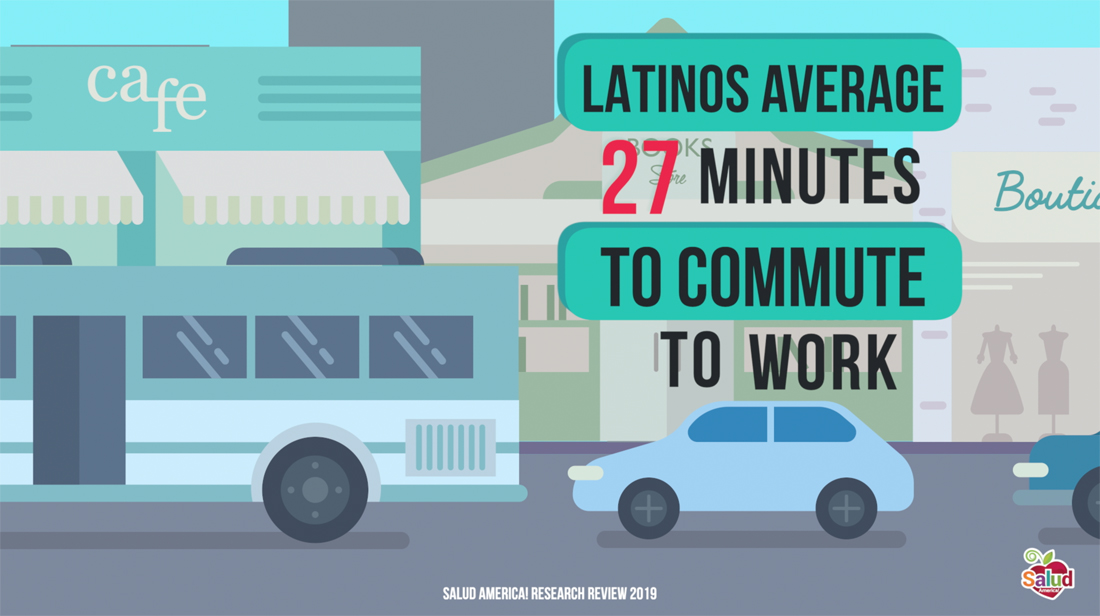

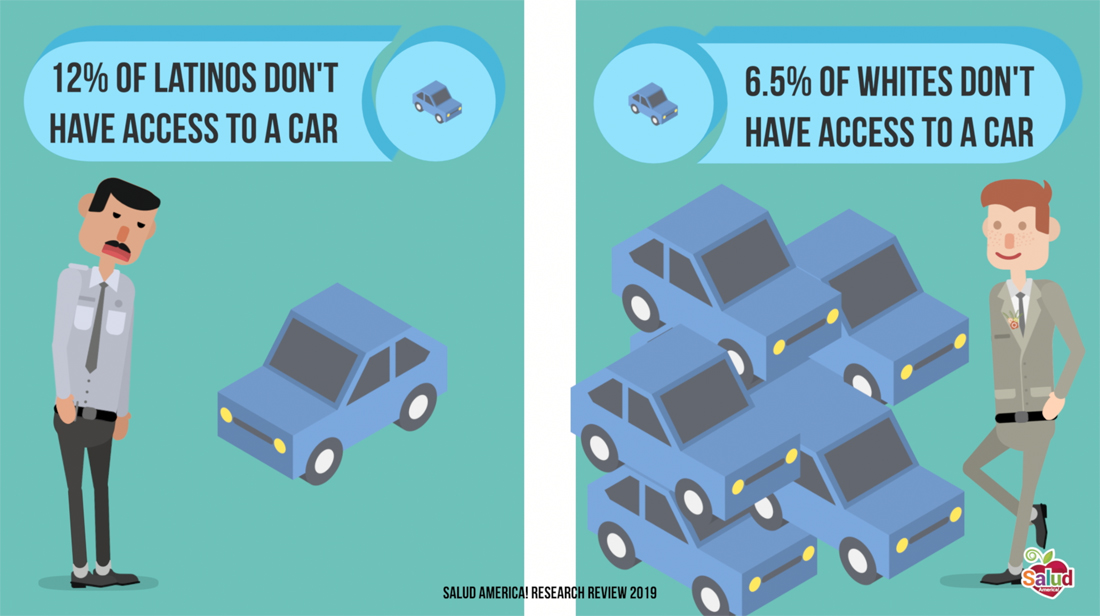

As a result, commute times and the number of modes of transportation used per commute is increasing for Latinos in the U.S., who often walk, bike and use transit or vehicles in a single commute [9, 41]. Latinos spend 26.9 minutes on average to commute to work, a longer time than their White peers (25.1 minutes), according to the National Equity Atlas. Also, a higher percentage of Latino households do not have access to a car (12%) than White households (6.5%) [44].

Why Do Latinos Face Transportation Obstacles?

Two studies analyzed the transportation barriers faced by Latinos in diverse regions of the United States.

The first study, by Barajas and colleagues directly surveyed and interviewed low-income Latinos residing in the San Francisco Bay Area, including San Francisco itself, as well as Berkeley, Oakland, San Jose, and the regions in between [41].

The second study, by Williams and colleagues directly surveyed and interviewed low-income Latinos in Massachusetts, including East Boston, Lynn, Springfield, Worcester and their environs [9].

Both studies spanned a range of transportation environments with varying access to public transit. Interestingly, in both studies, the same primary barriers to transportation were reported: transit fare affordability (cost), schedule reliability, and route insufficiency.

Both studies spanned a range of transportation environments with varying access to public transit. Interestingly, in both studies, the same primary barriers to transportation were reported: transit fare affordability (cost), schedule reliability, and route insufficiency.

For the lowest-income transit riders, managing household budgets to accommodate transit costs can add significant stress and force reduction of expenditure on other necessities including food, education, and healthcare [45].

One respondent, Gabriela, “spoke of taking her daughter out of school because of the added expense of taking her child there when she no longer worked near the school.”

I had just changed my job—and as I told you, I don’t drive—so then I had to change my daughter’s school. I took her out in third grade. Right now she’s in fifth grade and she wants to return to the [old] school, but I think about the expense of transportation, and as I said, I’m going in the same direction. I know that it’s going to be the same cost, it’s $2.35 to go, $2.35 to return, and again because I have to take her, return to my house, pick her up, and return to my house.

“Some of the cost would be alleviated by purchasing a monthly pass, but Gabriela noted that ‘sometimes it’s easier to spend $10 per day because you don’t have $80 to buy the monthly pass’ ” [41].

Latinos Face Unreliable Public Transit

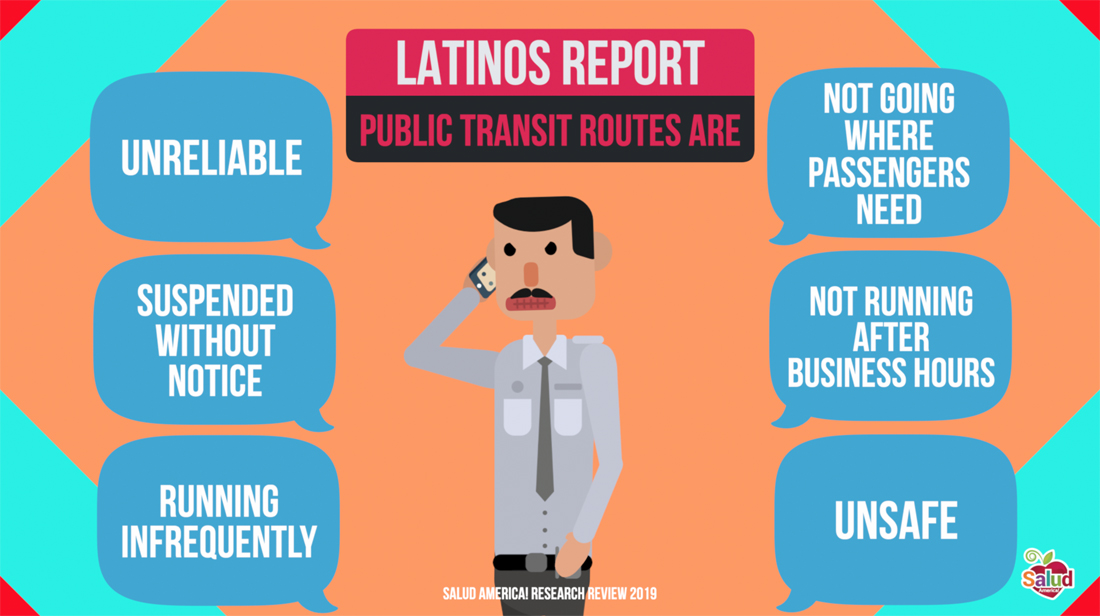

In areas with insufficient public transit, many Latinos report a lack of reliable service as a primary problem; for example, in both studies, interview respondents reported routinely leaving for work early because they could not depend on transit schedules getting them to work on time [9].

As Barajas notes, “For a trip that might take 20 minutes by car, some interviewees reported leaving up to two hours early to be sure they arrived to work on time” [41].

As Barajas notes, “For a trip that might take 20 minutes by car, some interviewees reported leaving up to two hours early to be sure they arrived to work on time” [41].

Others reported that many routes were suspended without notice, did not get them where they needed to go (to the daycare to pick up their kids, to suburban office parks or industrial complexes for their jobs) or did not run at the times they needed (after hours for community college night classes). Many routes ran only once per hour, or less often [9].

The Cost of Relying on Car Rides

As a result, many Latinos resort to automobiles as their primary mode of transport, but this comes at a financial and legal cost [9].

In the Bay Area, 15% of low-income Latinos had access to a car every day of the week, 16% had access 1-6 days of the week, and the rest had no access to a car; there was no difference in vehicle access between native-born and immigrant low-income Latinos [41]. Many reported that the cost of car ownership and repairs resulted in foregoing the purchase of other necessities including food and healthcare [9]. Latinos without cars often reported another person’s car as their primary mode of transport.

In Springfield, Massachusetts, 25% of Latinos reported that this was their primary means of transit [9]. In that same survey, 43% of respondents did not have a driver’s license, suggesting that many of these drivers are driving themselves and others illegally. Many respondents reported bargaining goods and services for rides, or having to come up with money to convince neighbors, relatives, or friends to drive them places. Most participants were not comfortable with this dependence on others for transportation, reported being late to work and appointments because of these unstable arrangements, and agreed with the statement, “if public transportation was better, I would drive and/or be driven less” [9].

In Springfield, Massachusetts, 25% of Latinos reported that this was their primary means of transit [9]. In that same survey, 43% of respondents did not have a driver’s license, suggesting that many of these drivers are driving themselves and others illegally. Many respondents reported bargaining goods and services for rides, or having to come up with money to convince neighbors, relatives, or friends to drive them places. Most participants were not comfortable with this dependence on others for transportation, reported being late to work and appointments because of these unstable arrangements, and agreed with the statement, “if public transportation was better, I would drive and/or be driven less” [9].

Support for more organized systems of these informal transportation arrangements could improve connectivity between places of residence and places of employment for low-income Latinos.

Both Barajas et al. and Williams et al. found that Latinos were unwilling to substitute public transit for driving when they had the option to drive or get a ride, suggesting they use car access for particular purposes that transit does not serve, or when their experiences on public transit have been unpleasant or unsafe [9, 41].

Most respondents reported greater access to jobs as the primary reason for preferring a vehicle for transport, suggesting that insufficient transit coverage is a problem for low-income Latinos.

The Problem of Local Funding for Public Transit

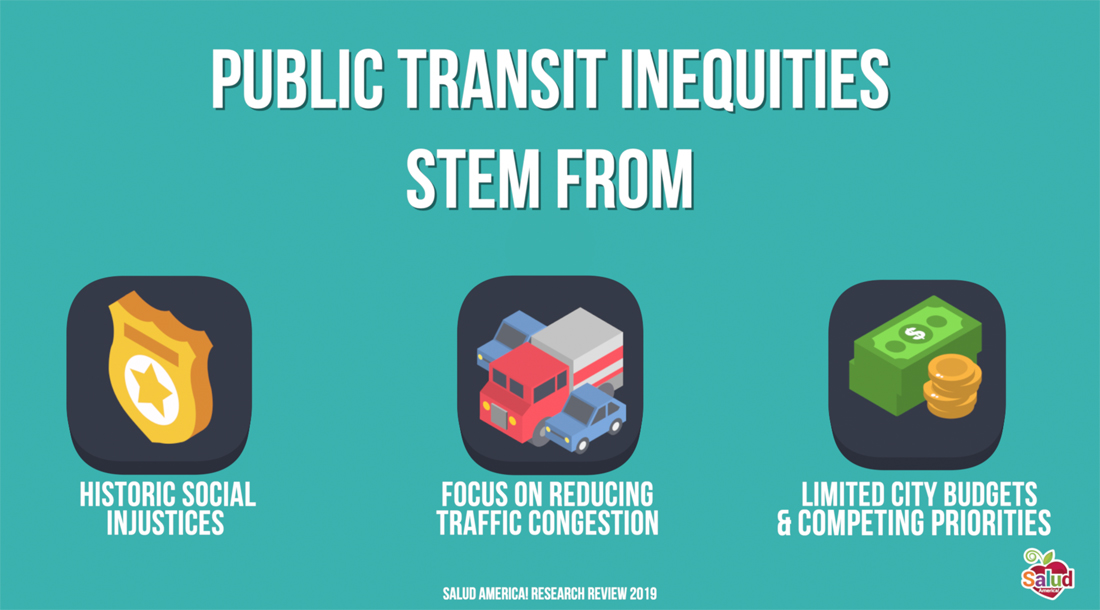

Environmental, economic, and social equity goals often compete for attention from policy makers in transportation-planning decision making [46].

The current public funding crisis is limiting agencies’ ability to expand services and enhance connections between jobs and households [42]. Often, transportation planning decisions in North America place a stronger focus on local environmental concerns and traffic congestion reduction than on social equity [46].

Quick links from our Research Review »

More from our Research Review »

- Executive Summary

- Introduction & Methods: Latino Housing, Transportation, and Green Space

- Research: Latino Families Burdened by Housing Costs, Eviction

- Research: Latino Rural Migration Led to Housing, Transportation Inequities

- Research: Latinos Face Big Public Transportation Challenges

- Research: Latino Communities Lack Accessible Green Space

- Strategy: How to Increase Affordable Housing in Latino Communities

- Strategy: How Transit-Oriented Development Benefit Latinos

- Strategy: Improve Public Transit to Improve Latino Quality of Life

- Strategy: Green Space Projects Can Boost Latino Health

- Strategy: Latino Community Involvement Can Spur Environmental Justice

- Policy Implications: Latino Housing, Transportation, and Green Space

- Future Research Needs: Latino Housing, Transportation, and Green Space

References for this section »

9. Williams, E. (2014). Transportation Dilemmas Facing Low-Income Latinos in Massachusetts Transportation Research Board. Transportation Dilemmas Facing Low-Income Latinos in Massachusetts Transportation Research Board.

39. Anderson, M. (2016). Who relies on public transit in the U.S. in Numbers, Facts, and Trends Shaping Your World Pew Research Center.

40. Emmons, W. R., & Noeth, B. J. (2013). The Nation’s Wealth Recovery Since 2009 Conceals Vastly Different Balance-Sheet Realities Among American’s Families. in In the Balance Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

41. Barajas, J. M., Chatman, D. G., & Agrawal, A. W. (2015). Exploring Bicycle and Public Transit Use by Low-Income Latino Immigrants: A Mixed-Methods Study in the San Francisco Bay Area, 89.

42. Tomer, A. (2012). Where the Jobs Are: Employers Access to Labor By Transit. Brookings. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/11-transit-labor-tomer-full-paper.pdf

43. Blumenberg, E. (2009). Moving In and Moving Around: Immigrants, Travel Behavior, and Implications for Transport Policy. Transportation Letters, 1(2), 169–180.

44. PolicyLink, & USC Program for Environmental and Regional Equity. (2015). National Equity Atlas: Indicators, Commute Time, United States. The Atlas | National Equity Atlas. Retrieved April 30, 2019, from https://nationalequityatlas.org/indicators/Commute_time/By_race~ethnicity%3A49816/United_States/false/Year%28s%29%3A2015/Mode_of_transit%3AAll

45. Agrawal, A. W., Blumenberg, E. A., Abel, S., & others. (2011). Getting Around When You’re Just Getting By: The Travel Behavior and Transportation Expenditures of Low-Income Adults. Mineta Transportation Institute.

46. Manaugh, K., Badami, M. G., & El-Geneidy, A. M. (2015). Integrating Social Equity Into Urban Transportation Planning: A Critical Evaluation of Equity Objectives and Measures in Transportation Plans in North America. Transport Policy, 37, 167–176.

Explore More:

Transportation & MobilityBy The Numbers

27

percent

of Latinos rely on public transit (compared to 14% of whites).