Share On Social!

The safety of roads and sidewalks impacts everyone.

Although Complete Streets initiatives are traditionally led by a transportation or public works sector, the public health organizations have played a role in communities across the country.

A new report from the University of Chicago’s Institute for Health Research and Policy provides key strategies from public health agencies, advocates, and practitioners in 15 U.S. jurisdictions who have engaged in Complete Streets-related initiatives in their communities.

Why Complete Streets?

Complete Streets initiatives aim to create more equitable transportation systems by providing affordable, convenient, and accessible modes of mobility for all users.

This includes individuals who rely on walking, biking, and public transit as their sole source of transit. It also concerns those who are more likely to face transportation barriers such as increased crime, harassment, and poor infrastructure.

Complete Streets can help people in numerous ways, including:

- Being more active, reducing risk for chronic disease, and improving health

- Increasing use of multimodal options, reducing vehicle miles traveled, and improving air quality

- Reducing injuries and deaths from motor vehicle crashes

- Supporting economic growth

- Increasing independence, social cohesion, and access to opportunity

That’s why public health professionals got involved.

For example, in 2010, the City of San Antonio (64% Latino) and its Metropolitan Health District set up a Complete Streets Working Group. They then worked with the Planning and Community Development Department to push city officials to approve a their policy.

However, like many cities, implementation is a struggle.

So, where and how were health professionals successfully getting involved in Complete Streets?

This question led the Physical Activity Research Center (PARC) to commission a case study report of best practices regarding public health involvement in the Complete Street initiatives.

Engaging Public Health in Complete Streets

The 2018 study, Best Practices in Engaging Public Health in Complete Streets Initiatives, researched how the health community played a role in the development, adoption, as well as implementation and evaluation of various projects.

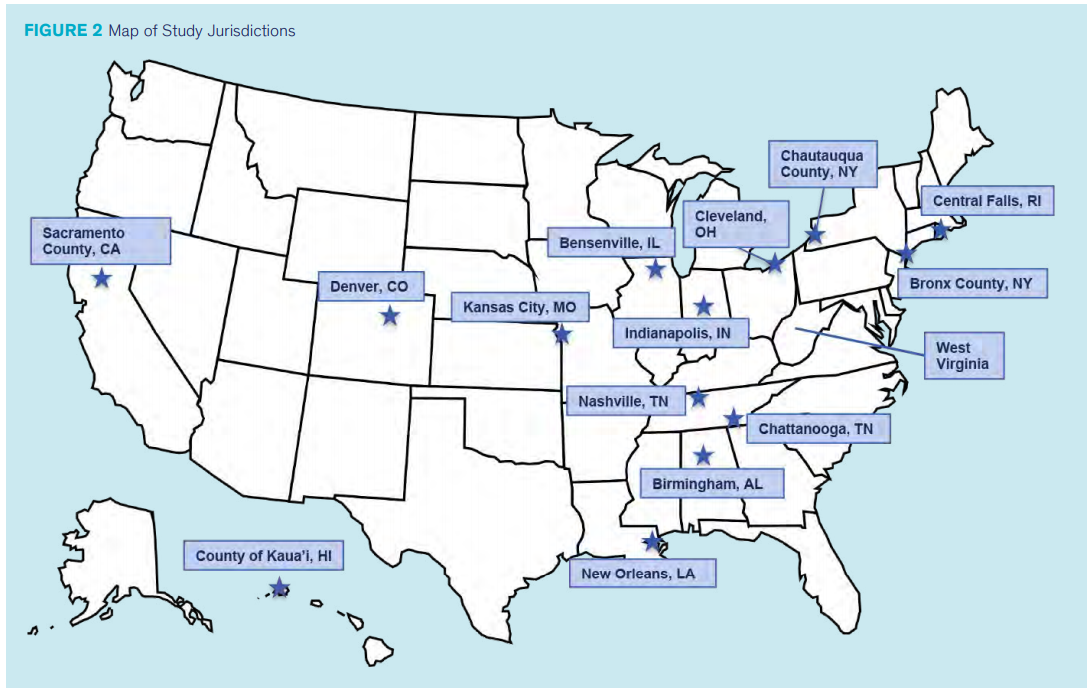

The report findings stem from qualitative research involving up to 30 key informant interviews in 15 identified jurisdictions from across the country.

The report findings stem from qualitative research involving up to 30 key informant interviews in 15 identified jurisdictions from across the country.

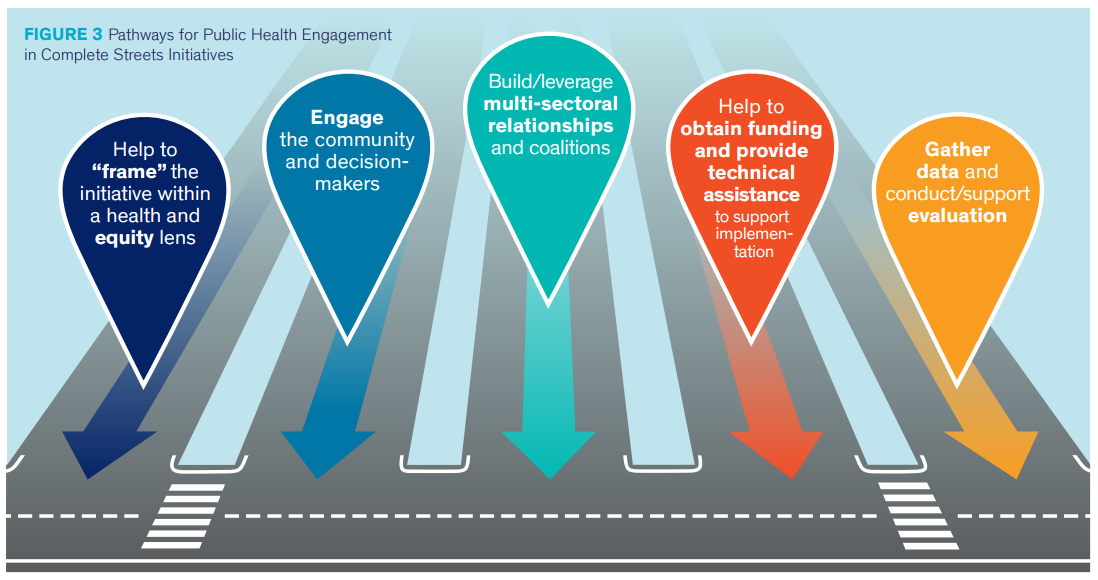

Key recommendations include:

- Provide technical assistance, support to advocacy groups and coalitions

- Help to “frame” Complete Streets in terms that resonate with decisionmakers and community members from a health, equity, injury prevention, and economic development lens

- Focus on equity issues through all stages of the Complete Streets policy-making process

- Build and/or leverage multi-sectoral collaborations identify internal champions

- Engage the community in the Complete Streets policy-making process

- Provide technical assistance and grantsmanship expertise to support implementation efforts

- Support data collection and evaluation efforts

The study’s appendices give further insight:

- Appendix A provides an overview of the study methods

- Appendix B gives a list of the agencies and stakeholders who participated in this study by jurisdiction

- Appendix C shows examples of equity provisions included in their policies/plans and/or strategies for addressing equity

- Appendix D approaches that jurisdictions have taken to plan for or actively engage in evaluation of Complete Streets initiatives

- Appendix E profiles and summaries for each of the 15 jurisdictions studied herein

Equity matters because street improvements often occur in white, wealthy neighborhoods.

“Many jurisdictions employed data-driven efforts as a starting point to identify inequities such as differences in health outcomes, lack of access to cars, and ability to access grocery stores, employment opportunities, and public transportation, that could be addressed through Complete Streets initiatives,” the report states.

Lessons Learned

County health departments can serve in a technical assistance capacity to facilitate Complete Streets policy-making at the municipal level.

In Bensenville, Illinois (48.1% Latino), for example, the county health department was involved in an existing coalition to help review existing information to identify areas of opportunity for “equitable transportation improvements.” Using datasets, they were used to create a Demographic Equity Map that illustrated priority areas that needed bicycle and pedestrian facilities. The Index included crash data, information on access to local destinations, alignment with other infrastructure projects, and connectivity to the regional bike network. It went to provide the basis for recommended priority projects ranging from bike lanes, to sidewalks, to specific intersection improvements such as traffic signals or curb ramps.

County health departments can push to include implementation in the policy language and specify oversight or advisory committees, including membership requirements.

In Birmingham, Alabama (3.4% Latino), for example, the Complete Streets policy required the formation of two committees: the Technical Oversight Committee and the Complete Streets Advisory Committee. The internal Technical Oversight Committee bears the responsibility of reviewing transportation initiatives and determining if Complete Streets components can be incorporated. They are also charged in creating Complete Streets implementation policies and procedures, including performance metrics. The Complete Streets Advisory Committee is required to meet quarterly and advise the Technical Oversight Committee on compliance, provide feedback on implementation, and support implementation of the Complete Streets policy.

County health departments can push to prioritize the implementation of Complete Streets initiatives in disadvantaged communities that explicitly includes policy language requiring organizations to address inequity.

In Denver, Colorado (30.8% Latino), for example, the Department of Public Health and Environment created the Denver Neighborhood Equity Index, that maps every neighborhood in the city. The resource was designed to help decision makers visually assess where investment and resources can be distributed based on neighborhood needs. It also creates a common language platform for Denver’s city departments to use when discussing equity.

These findings further help public health agencies and advocates engage in the policy-making process.

Share this report with health, equity, and walkability advocates to incorporate public health into Complete Streets policies.

By The Numbers

27

percent

of Latinos rely on public transit (compared to 14% of whites).