Share On Social!

When he was a kid, Rey Saldaña couldn’t swim. His family couldn’t afford lessons.

So Saldaña was a little scared as he and his second-grade classmates walked into a chlorine-smelling aquatic center to learn how to swim as part of a federally funded program in San Antonio, Texas (63.34% Latino).

He overcame his fear and learned to swim, thanks to that “Learn to Swim” program.

Sadly, the program folded before his younger brother could participate.

When Saldaña became a member of the San Antonio City Council many years later, he helped recreate the Learn to Swim program to reduce drowning and build kids’ confidence.

He didn’t stop there.

Saldaña worked with others to on two big projects—renovating an aquatic center and building a new one—that could create a new culture of swimming for at-risk kids in San Antonio’s mostly Latino South Side.

Historic Inequity in Pool Access

Source: Joey Palacios/Texas Public Radio

Saldaña wasn’t going to have many chances to learn to swim as a kid.

The city’s South Side, where he lived, had one natatorium.

The North Side had five.

Many community members remember a time when pools were accessible, but over time have all been cemented over or gated in, Saldaña said

“[The Learn to Swim program] is literally the only way I learned to swim,” Saldaña said. “There was no other venue that my parents could have afforded lessons. That is still true today.”

Because certain populations have less access to pools and swimming lessons, a historic segregation in San Antonio and other cities spurs disparities in drowning and swim ability.

Fortunately, many city leaders are taking action to improve equitable access to pools, teach all children how to swim, and reduce disparities in drowning rates and health.

For example, in a low-income area of Minneapolis, Minn., foster mom Hannah Lieder started a seven-year battle to prevent the closure of the city’s last indoor public pool, resulting in a groundbreaking city-school partnership to renovate and expand the facility.

Parks and schools partnered in Broward Country, Fla., to bus students to pools to teach them to swim.

Saldaña, too, wanted to prioritize swimming when he became a city leader.

In 2011, he was elected to the San Antonio City Council as a representative for District 4 in the city’s South Side (80% Latino), where poverty is higher and education rates are lower than other areas.

Source: Rey Saldaña Twitter (@rey4sa)

Saldaña wanted to teach local kids how swimming can save their lives, build their confidence, and open a whole new-underwater-world of opportunities.

But where could he start?

An Aging Aquatic Center

Saldaña got a fortuitous call in 2013.

Dr. Mike Flores, president of Palo Alto College, reached out to discuss a funding request to improve the school’s Palo Alto College Aquatic Center—the only such facility on the South Side.

The Palo Alto College Aquatic Center needed maintenance and upgrades. It was built in 1991, and is half-owned by the city. It annually hosts 31,000 swimmers and is open to school teams, club teams, military training and the public thanks to a shared use agreement between the Alamo Colleges and the City of San Antonio. It also has hosted the U.S. Open, the USA Swimming Junior Olympics, the Olympic Festival, and several NCAA Championships.

Flores invited Saldaña and his staff to tour the facility.

“He walked us through the natatorium and showed us upgrades that it currently needed as well as anticipated maintenance,” Saldaña said.

The city’s upcoming 2017-2022 municipal bond program was one way to pay for the upgrades.

Cities and school districts use bond programs as a tool to pay for large, high-cost improvements like streets, sidewalks, flood control, parks, and aquatic centers. Bond programs start with a planning phase shaped by public input. City officials then agree to a list of projects for the bond. The bond then goes before voters.

Before planning started for the 2017-2022 city bond, Saldaña and his staff fielded many phone calls from parents asking for swimming lessons and improved access to pools in their neighborhoods.

He knew maintaining and upgrading the existing aquatic center was important.

But if voters were going to be asked to OK bond funds for the Palo Alto College Aquatic Center, Saldaña and Flores agreed that the facility should be used to its potential by the entire community.

Saldaña, Flores, and Palo Alto athletics officials started planning how the facility could better serve the community. Palo Alto College Aquatic Center already opened to the public on evenings and weekends. But the facility was underutilized during the day.

“We wanted to get more out of public investment in a public facility to make sure it was reaching the public, like those going to school and those more vulnerable in the community,” Saldaña said.

Remembering his own childhood swim experience, Saldaña asked:

“What if we brought swimming lessons back?”

Recreating a Free Swim Lesson Program

Saldaña and Flores discussed the cost of reinstating free swimming lessons for students during the day, similar to the Learn to Swim program that benefited Saldaña.

They decided that, based on Swim America’s recommendations for water safety curriculum, each local second-grader should go through a two-week program with 45-minute sessions per day. Students would learn the basic breathing, floating, and stroke skills.

“Free or low cost swimming lessons [are] often the only way many kids … will learn,” Saldaña said.

Flores agreed to host the lessons at the aquatic center during the day, as a community service and to attract more residents into higher education.

Saldaña still needed about $150,000 to pay for swimming instructors and transportation from schools to the aquatic center (bond funds are not able to pay for program costs).

Saldaña identified $50,000 in the city’s 2016-2017 fiscal year budget for programs.

“Securing funding for basic city services and identifying investments in projects that can improve the lives of our residents remains one of my top priorities for the community that has witnessed the steady progress of a district long-neglected yet full of so much potential,” said Saldaña, according to one source.

Source: Pitsco

He would have to ask local school districts to cover the rest, about $100,000.

Saldaña pitched the program to three local school districts—Southwest Independent School District (ISD), South San Antonio ISD, and Harlandale ISD.

Southwest and South San Antonio each approved $42,000 for the 2016-2017 school year.

Lloyd Verstuyft, a Southwest ISD grad who also has worked there for 28 years (including eight as superintendent), knew that programs like this don’t happen unless outside entities come together.

“Rey made it so appealing. It wouldn’t be affordable without these partnerships and the support he received outside the school,” Lloyd Verstuyft. “Our board overwhelming supported it.”

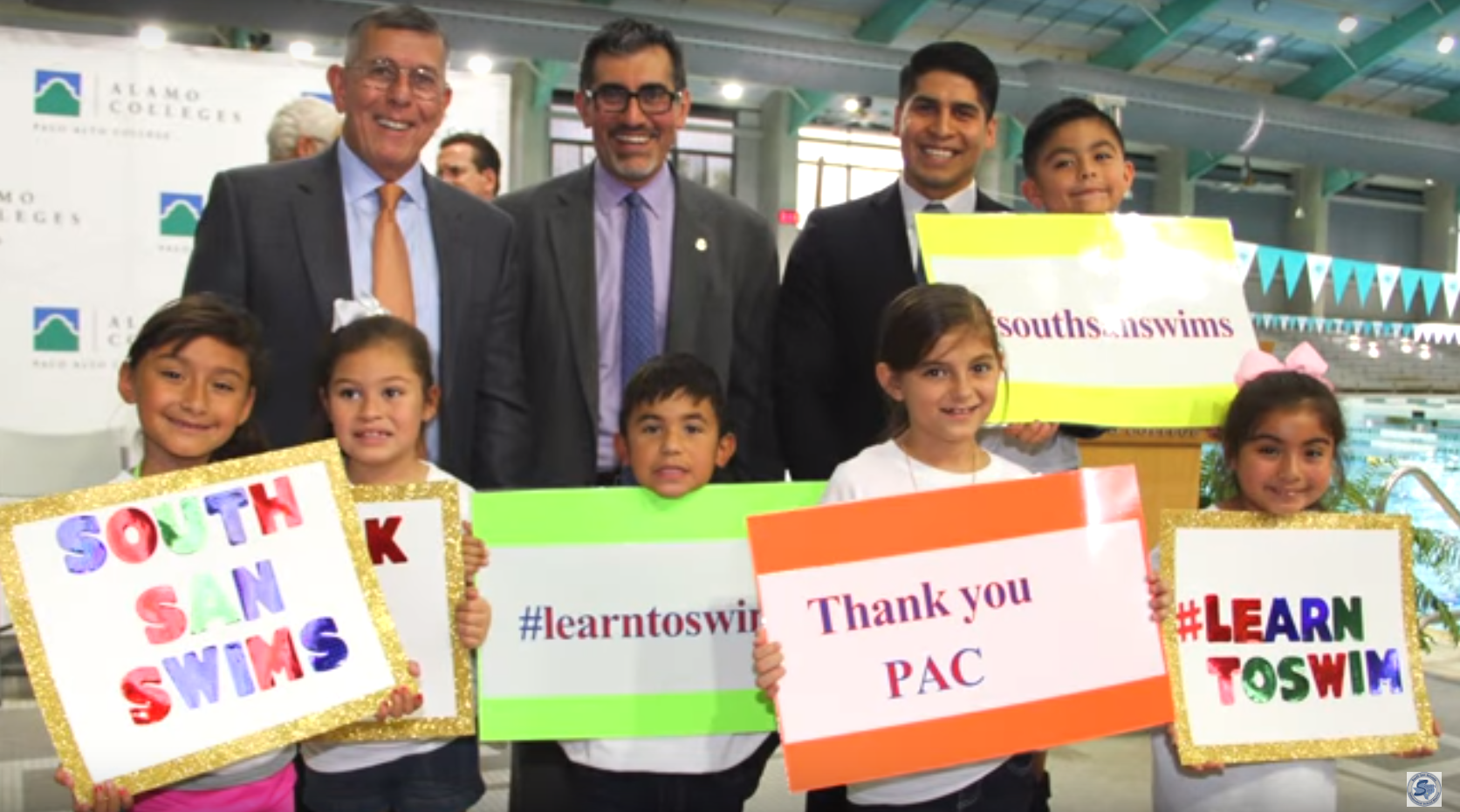

The program—thanks to Palo Alto College Aquatic Center as host and funding from the City of San Antonio and the South San Antonio and Southwest school districts—launched in fall 2016.

That year, more than 1,500 students from two schools received free water safety lessons.

August 2018 UPDATE: 4,500 second grades have received water safety lessons through the Learn to Swim program.

“You never really know how many lives you’ve saved,” Verstuyft said. “To have the ability to be in the pool with a certified, qualified instructor is so valuable.”

Continuing Plans for Aquatic Center Renovations

The swim program increased use of the Palo Alto College Aquatic Center—making the maintenance and upgrade of the facility an even bigger priority for Saldaña and Flores.

Saldaña continued working within the City of San Antonio to ensure the Palo Alto College Aquatic Center project made it on the list of recommended projects for the city’s 2017-2022 bond, which was to go before voters in May 2017.

Flores also worked within the Alamo Colleges District to ensure the project made it onto the Alamo College District (ACD) bond election for improvement projects across their five campuses, which also was set to go before voters in May 2017.

But, as it turns out, it wasn’t the only swim project that made the city’s bond list.

New Idea: A Second Swim Facility on the South Side

Verstuyft and Saldaña had been discussing an idea to build a second aquatic facility on the South Side, on the Southwest ISD campus where 83% of students are economically disadvantaged.

“We all share Palo Alto, which is great, but when there are so many partners trying to access the only natatorium on the South Side, it creates scheduling conflicts,” Verstuyft said.

Source: South San Antonio ISD

If Southwest sold the city some land, could the city help pay for a new natatorium?

Saldaña, Verstuyft and others at Southwest explored design plans for a new natatorium which could hold competition meets. They talked to many experts, including American Swimming Coaches Hall of Famer George Block, and estimated that they would need about $15 million for construction.

Saldaña wanted to add the Southwest natatorium to the city’s 2017-2022 bond program.

Southwest also included the project in its own 2018 bond program.

Unlike the Palo Alto Aquatic Center, which is half owned by the city, the proposed Southwest ISD Natatorium would be solely owned and operated by the school district. Through a planned shared use agreement, the facility would also be available publicly and for other districts.

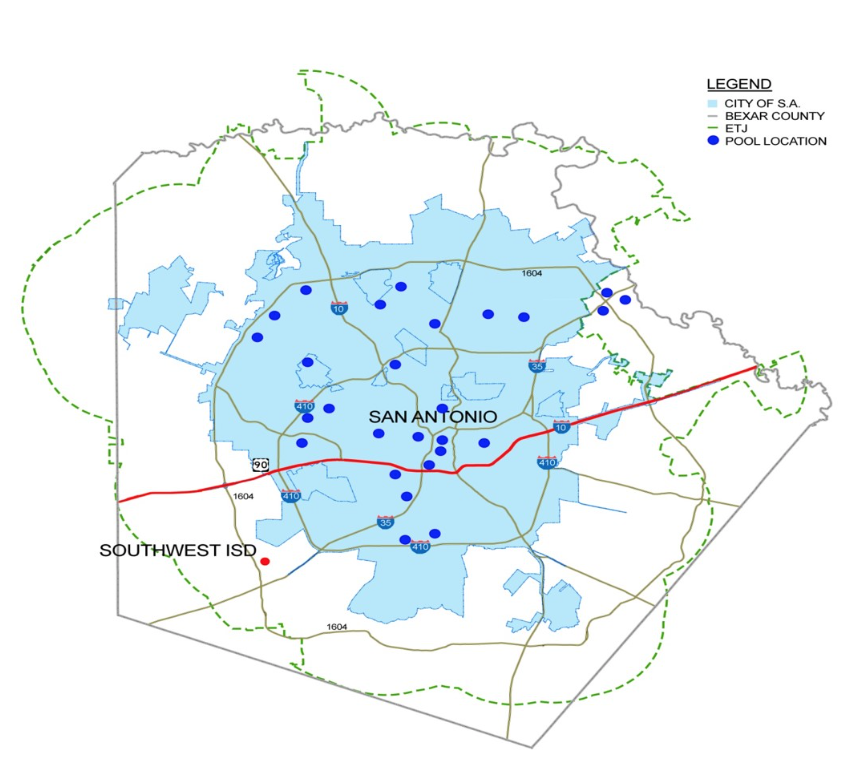

October 2018 UPDATE: The natatorium is on the general election ballot as part of Southwest Independent School District’s bond program. Currently there are 23 City/County/ETJ swimming pools accessible North of Hwy. 90 and only 4 swimming pools South of Hwy. 90, according to SWISD’s proposed 2018 bond projects. A significant portion of our community are non-swimmers especially school aged children and SWISD would support efforts to train and encourage water safety programs.

November 2018 UPDATE: The Southwest ISD Bond passed with 67% approval, which includes funds for the Natatorium.

“Councilman Saldaña brought people back to the table [regarding swimming] on the South Side,” Verstuyft said. “He has a passion for creating opportunity for our youth and for our entire community.”

Making the Bond Program Lists

Saldaña requested $5.3 million in deferred maintenance costs for the Palo Alto College Aquatic Center and $4 million for the Southwest ISD Natatorium.

If approved, the $4 million for the Southwest ISD Natatorium would be leveraged for $10-11 million from the Southwest ISD bond program, which is expected to go to voters in late 2018.

Source: SSAISD Palo Alto Elementary School Twitter (@SSAISDPaloAltoES)

Both projects made an initial cut for the list of projects for the city’s bond program.

“Internally, it was mostly me bothering people and being a curmudgeon about the federal government no longer offering the Learn to Swim program,” Saldaña said.

In public hearings about the bond, residents provided feedback on the initial list.

Several residents, including Jessica Esquiver and Beatriz Joseph, stated support for maintenance and improvements to the Palo Alto College Aquatics Center.

In Esquiver’s two-minute speech, she described her and her family’s experience with the newly implemented Learn to Swim program and showed support for the swim improvements. In Joseph’s speech to the board committee, she noted the 31,000 people that use the Aquatics Center annually and the 2,000 second-graders who had received free swimming lessons.

On Jan. 11, 2017, each of the city’s five bond committees presented their final committee recommendations to the City Council.

In February, the council approved 180 projects to be funded, including the two swim projects.

The swim projects ($5.3 million for Palo Alto and $4 million for Southwest ISD Natatorium) would now appear on the May 6, 2017, ballot, for San Antonio voters, under Proposition 3: Parks, Recreation and Open Space Improvements, along with 77 other projects for a total of $187,313,000.

Also on the May 6, 2017, ballot, Bexar County residents would vote on $450 million for the Alamo Colleges District General Obligation Bond, which included $5.7 million for the Palo Alto College Aquatic Center renovation.

Voters Approve Swim Projects

On May 6, 2017, San Antonio voters approved the City of San Antonio 2017-2022 Bond Program, including $5.3 million for the Palo Alto College Aquatic Center and $4 million for the Southwest ISD Natatorium.

Source: South San Antonio ISD Twitter (@ssaisd)

Bexar County voters approved the 2017 Alamo Community College District Bond, which included $5.7 million for maintenance and improvements to the Palo Alto College Aquatic Center.

On final hurdle remains—the Southwest ISD bond election.

That election, estimated for $60 million in overall projects including $10-11 million for the natatorium, is expected to go before voters between September 2018 and April 2019.

Additionally, after first-year success, Saldaña sought another $50,000 in the 2017-2018 annual budget to continue the recreated Learn to Swim program during the 2017-2018 school year.

It was approved.

“Introducing kids to water at an early age is important part of a holistic lifestyle,” said Verstuyft of Southwest ISD. “A well-rounded education experience is reading, writing, arithmetic and life lessons, like water safety and team collaboration.”

“On one side of the pool, you have military training, and on the other side, you have six-year-olds learning to swim,” Saldaña said.

August 2018 UPDATE: 4,500 second graders have received water safety lessons through the Learn to Swim program.

October 2018 UPDATE: A natatorium is on the general election ballot as part of Southwest Independent School District’s bond program. The City of San Antonio has already allocated $4 million for the natatorium, which would be accessible to the public and open during the summer.

“Verstuyft said the district would use it both for athletics and for water-safety classes for Southwest ISD’s second-graders,” according to the Rivard Report.

“A significant portion of our community are non-swimmers especially school aged children and SWISD would support efforts to train and encourage water safety programs,” according to SWISD’s proposed 2018 bond projects.

November 2018 UPDATE: The Southwest ISD Bond passed with 67% approval, which includes funds for the natatorium. The proposed site will be on the 9,777 acres owned by SWISD adjacent to McAuliffe MS, with the proposed facility having 35,000 square feet of building area, according to SWISD.

By The Numbers

33

percent

of Latinos live within walking distance (<1 mile) of a park

This success story was produced by Salud America! with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The stories are intended for educational and informative purposes. References to specific policymakers, individuals, schools, policies, or companies have been included solely to advance these purposes and do not constitute an endorsement, sponsorship, or recommendation. Stories are based on and told by real community members and are the opinions and views of the individuals whose stories are told. Organization and activities described were not supported by Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and do not necessarily represent the views of Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.