Share On Social!

Neighborhood leaders and residents like Paul D. López and Fany Mendez in the Denver, Colo., neighborhood of Westwood worked together with local organizations to tackle safety concerns on Morrison Road, an arterial street that bisected their neighborhood. In addition to safety issues, they were also concerned about health, because kids can’t play and people can’t walk on busy, unsafe streets. Their efforts led to a pedestrian-activated traffic light, traffic calming features, medians, and aesthetically-pleasing infrastructure and landscaping to make the road more accessible to all.

Unsafe Street Scares Kids and Families

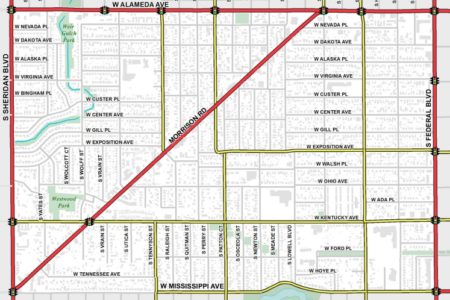

Paul D. López, the District 3 City Councilmember in Denver, Colo. (31.8% Latino), grew up a few blocks from his current office on Morrison Road, a busy main thoroughfare that essentially halves the neighborhood of Westwood, an area with a large low-income Latino population.

Vehicular traffic and safety on Morrison Road had long been negatively affecting Westwood’s health and economic development, López said.

The road is not friendly for pedestrians or bicycle riders, and many residents are physically inactive and at higher risk for heart disease, stroke, and diabetes, said Fany Mendez, a community connector with Westwood Unidos—a group of organizations and residents that push for a safer, healthier Westwood.

“Cars speed down the corridor; there aren’t crosswalks,” Mendez said. “It is a challenge for many community members to walk from one side of the street to the other.”

Indeed, many families don’t let their kids to cross the street to a neighborhood park.

“There had been some pedestrian fatalities,” said Tracy Kaye, coordinator for what would become Westwood Healthy Places. “People would talk about safety in the neighborhood. They would talk about the speeding traffic and how they didn’t want their kids to be anywhere near Morrison Road.”

López had long prioritized road improvements.

“Since the day I was elected, we wanted to create a corridor that people don’t just ignore and drive through, but a corridor that people come to and stay,” he said.

Meanwhile, López, Mendez, and Kaye were seeing skyrocketing childhood obesity rates across Colorado, from 28.4% in 2004 to 31.4% in 2011.

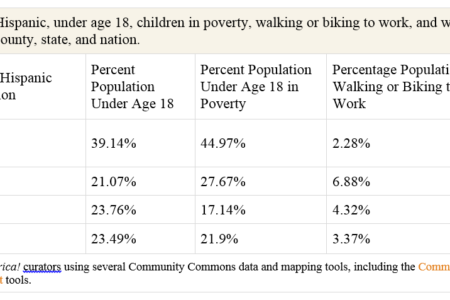

Westwood’s 17,000 residents are mostly Latino (81%). The area has more children younger than 18 than Denver County (39% vs. 21%), more of whom live in poverty (45% vs. 28%) and face language barriers.

Latino and low-income kids often lack access to safe places to play and be physically active like parks and sidewalks, which contributes to obesity. Research consistently shows an association between how neighborhoods and cities are designed with how physically active the residents are.

Westwood has both the least amount of park acreage in Denver and the unsafe Morrison Road thoroughfare.

Overall, numerous residents felt that the road’s infrastructure was inferior to those in wealthier neighborhoods. It divided their community and that negatively impacted the physical activity, health, and economic development of the neighborhood.

What could residents and leaders do to improve neighborhood design to boost physical activity?

Enhancing safety on Morrison Road was a good starting point, Kaye said.

“We have a really young population and need a safe place for them to play,” Kaye said.

As far back as 1986, neighborhood plans called for improvements to pedestrian infrastructure, such as a major pedestrian crossing, better streetscapes, and slower speed limits.

But nothing had been done for 27 years, while the population and traffic boomed.

López felt that Morrison Road was key to improving local safety, health, community connectedness, economic resilience, and equity, and that Latino policymakers should be involved in increasing opportunities for healthy eating and active living.

“We don’t want families to feel unsafe walking in their neighborhood because of speeding cars,” López said. “You don’t want folks to leave the neighborhood in their cars to go to a movie or to buy diapers or food.”

Incorporate Physical Activity into Land Use Plan

Around 2007, Rachel Cleaves, currently the LiveWell Westwood Coordinator with Re:Vision International, conducted community needs assessments and identified assets and challenges.

Cleaves was starting to talk about possible healthy changes in Westwood with local leaders like Joseph Teipel and Eric Kornacki of Re:Vision International, which helps build resilient communities by developing local leaders, food systems, and locally-owned economies.

She also found a new grant opportunity.

In 2012, the Colorado Health Foundation, a nonprofit that promotes healthy living and health care, contacted the Urban Land Institute (ULI) to obtain advice on public health issues related to land use for the Healthy Places: Designing an Active Colorado initiative.

The Healthy Places initiative, designed to incorporate physical activity into land development and land use, was seeking grant proposals for submission by October 2013.

Cleaves alerted Re:Vision, Westwood Unidos, and others to the Healthy Place grant opportunity. Because Westwood Unidos is not a registered nonprofit, they asked Re:Vision to be their fiscal agent for the grant initative, and asked López to write a letter of support.

“My job is to help remove barriers,” López said. “Show up, speak about it, and write letters to get grants. We gotta get behind these folks and amplify.”

“My job is to help remove barriers,” López said. “Show up, speak about it, and write letters to get grants. We gotta get behind these folks and amplify.”

Westwood was one of three communities selected in 2014 to receive $1 million over three years.

Kaye was hired to be the Westwood Healthy Places Coordinator to talk to community members and form a steering committee to discuss how to use the new funding to address neighborhood concerns.

“We explained to them we have this chunk of money and we have all these projects needed in the neighborhood, but we have to prioritize them,” Kaye said. “And if you want Healthy Places [funding], you have to participate in the steering committee and you have to be part of the process with the community.”

The Colorado Health Foundation started by learning more about neighborhood needs. In May 2013, they contracted with the Urban Land Institute (ULI) for a series of three Advisory Services panels with land use, transportation, real estate, architectural, and public health experts for three days.

López was involved and walked the neighborhood streets with panelists, community members, and other city leaders to ensure the community’s voice was heard.

Morrison Road soon emerged as a focal point.

“The panel believes that Morrison Road should be enhanced to become the cultural and physical focus of Westwood, with a community mercado and plaza where people can gather for conversation and interaction, where community festivals and events can be held, and where vendors can sell their wares,” according to an excerpt from the ULI report.

Westwood Unidos also hosted community meetings and shared recommendations from the ULI report and asked for community input.

Based on feedback, they selected three projects and proposed monetary allotments: Morrison Road ($300,000), Parks ($150,000), and Neighborhood Connectivity ($150,000).

Committees formed to debate specifics of each of the three projects.

Top-Down and Bottom-Up Meetings

The Morrison Road committee met regularly with city leaders, local groups, and residents to discuss multiple land-use approaches that could slow traffic and create a more walkable, active lifestyle-friendly road, such as traffic signals, stop signs, widening sidewalks, narrowing traffic lanes, several types of curb extensions that narrow or angle the roadway in favor of more space for pedestrians (i.e., bulb outs, chokers, neckdowns), chicanes (artificial turns or curves that forces traffic to slow down), roundabouts, raised medians, raised intersections, road humps, and/or speed humps, as well as developing a master or implementation plan to comprehensively guide future growth and development.

“[The meetings helped identify] how we can really start to improve safety and walkability of the Morrison Road corridor to make it a destination for the neighborhood rather than the divider that it is now,” Kaye said.

For López, a member of the Morrison Road committee, a traffic light was vital.

“There was a need for this stop light since I was a kid,” he said. “But it was the biggest ticket item, so a lot of people were not happy about it. However, we were big proponents of the grant and helped pressure it in.”

In the meantime, in early 2015, as part of updating the Westwood Neighborhood Plan (which hadn’t been updated since 1986), the Denver Department of Environmental Health worked with the Denver Department of Community Planning and Development to conduct a Health Impact Assessment (HIA) in Westwood, as part of a new city policy to prioritize HIA’s for all neighborhood plans.

The HIA report was made available for public for comment in January 2016 and is currently being used to inform the updated Westwood Neighborhood Plan.

Also in 2015, Westwood Unidos, with support from Councilman Lopez’s office, BuCu West (a nonprofit organization to promote and support entrepreneurs, small business, cultural organizations and residents around the Morrison Road corridor), and the Colorado Health Foundation, sent a consolidated letter to the city traffic engineer requesting a speed study be done on Morrison Road.

The city agreed and installed tube counts to count volume and speed of cars at three points on Morrison Road. They reviewed accident reports and found 67 mid-block accidents on Morrison Road from 2011-2014.

“If we are interested in safety rather than moving cars, then we lower the speed,” said Michael Koslow, Senior Engineer with the Transportation and Mobility Division of Denver Public Works Department. “It’s essentially used as a cut through for people getting from Denver to southwest Denver, especially in mornings and afternoons, there is no break in traffic for pedestrians to safely cross.”

Although the city was in the process of developing a Westwood neighborhood plan, BuCu West were advocating to develop a master plan specifically for Morrison Road to be used for additional projects and development, projects that need to phased in over a longer period of time.

“We need to design for people,” said AnaCláudia Magalhães, Community Development Coordinator for BuCu West. “In order to make if safe, you have to change infrastructure. Only by design can you rethink the public right of way and fix the safety issues that we have.”

Healthy Places agreed to traffic signals, landscaped bump outs and medians, and a Morrison Road Streetscape Implementation Plan.

The city also agreed to lower the speed limit from 35 to 30 miles per hour.

“We went to city and told them this project has come to life because we have experts, residents, and we have some money to put towards it, but we need you to step up too,” Kaye said.

Calming Traffic and Encouraging Walkers

The landscaped bump outs and medians to slow traffic speed and improve pedestrian safety were estimated to cost about $800,000, but with some funding from Westwood, the Denver Public Works Department agreed to install a traffic signal, new speed limit signs, bulb outs, and medians.

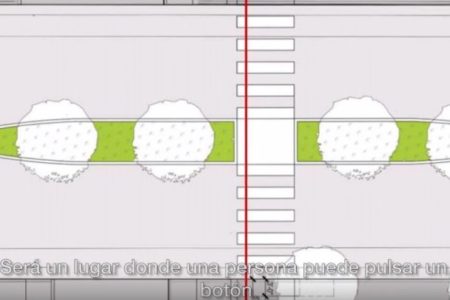

In fact, they fast-tracked the traffic signal project and installed the signal at Morrison’s intersection with Perry Road in August 2015.

“This light is a little bit special because it is pedestrian-activated,” Kaye said. “It prioritizes people on foot, which means you can push the button and you don’t have to wait for the timing of normal streets lights.”

In being cautious with city dollars—like many cities—Denver Public Works Department puts caps on individual project tasks. Unfortunately, this requires more independent contracts and more administrative work, which often slows the process-also like many cities.

Other typical complexities arise, such as ensuring ADA compliance involving private land, and working with local maintenance and business districts that maintain lighting and landscaping.

For example, they worked with BuCu West, which will maintain landscaping on Morrison Road.

“We have to have an agreement with a local maintenance district to make sure plantings are going to be maintained before we include them in the project,” Koslow said.

Still, construction for landscaped bulb outs and medians should be well underway in late 2016.

“Bulb outs and medians shorten the distance that pedestrians have to cross the busy street and narrow the feeling of the street,” Kaye said. “Driver’s automatic response is to slow down.”

Meanwhile, BuCu West has been developing and getting feedback on the Morrison Road Streetscape Implementation Plan, and plan to open it for public comment in June 2016. The will be looking for public and private funds, in the form of bond and capital improvement funds, as well as foundation donations and grants.

López said he is a proponent for a “mercado lineal,” or a linear Mercado, with public art, places to eat, and things to do, which is conceptualized in the Morrison Road Streetscape Implementation Plan.

Morrison Road improvements will address health equity.

There is a proven link between disadvantaged neighborhoods and poor health outcomes. Residents in these neighborhoods often don’t have the money to join a gym or visit it regularly, thus are less physically active. Additionally, these neighborhoods often lack safe, quality opportunities for physical activity, like sidewalks, parks, and trails, further contributing to disparities in physical activity levels.

“We were always thinking about safety and mobility for everyone,” Kaye said. “And how built environment projects can address these big issues.”

Everyone benefits, particularly those in disadvantaged areas, when communities build environments that support safe places for resident’s to be physically active. Implementing traffic calming devices is an effective and sustainable long-term method to improve pedestrian safety and, ultimately, increase physical activity levels for everyone in the community.

There are multiple other projects going on in the Westwood neighborhood, such as the Knox Court Neighborhood Bikeway, Cool Connected Westwood, Westwood Food Co-op, La Casita, and other Bu Cu West initiatives to connect people to safe places to play, healthy food, and public transit.

“Tracy Kaye, Rachel Cleaves, and others with Healthy Places are interested in adding amenities like benches, signage, and containerized landscaping,” Koslow said. “There is a bit of synergy with those Westwood projects to improve the entire neighborhood.”

López is also building on this energy and synergy to turn Westwood into a culturally authentic neighborhood that people can be proud of. As part of this cultural rebranding, he is advocating to rename Morrison Road, Cesar Chavez.

“Who better to embody community service, than Cesar Chavez,” he said.

Watch Colorado Health Foundation video about their Healthy Places Initiative in English and Spanish here.

Learn more about Healthy Places Initiatives going on Westwood and watch Colorado Health Foundation videos here.

References

1. U.S. Census Bureau. (2008). American Community Survey (ACS). 2009-2013. U.S. Department of Commerce, Washington, DC. Available.

2. U.S. Census Bureau. (2012). County Business Patterns. (CBP). 2013. U.S. Department of Commerce, Washington, DC. Available.1

3. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, USDA – Food Access Research Atlas (FARA). (2010). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC. Available.1

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP). 2012. Atlanta, GA. Available.1

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). 2005-09. Atlanta, GA. Available.1

6. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Area Health Resource File (AHRF). 2012. Washington, DC. Available.

By The Numbers

27

percent

of Latinos rely on public transit (compared to 14% of whites).

This success story was produced by Salud America! with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The stories are intended for educational and informative purposes. References to specific policymakers, individuals, schools, policies, or companies have been included solely to advance these purposes and do not constitute an endorsement, sponsorship, or recommendation. Stories are based on and told by real community members and are the opinions and views of the individuals whose stories are told. Organization and activities described were not supported by Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and do not necessarily represent the views of Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.