Share On Social!

In a Florida school district that didn’t provide health classes in high schools, a health educator, Risa Berrin, and her sister, Valerie Berrin, worked together to raise the bar on health education with their Health Information Project (HIP). HIP is a peer-to-peer program that allows students to teach each other about health problems, prevention, and how to access to local health resources toward reducing obesity, suicide, depression and other issues.

EMERGENCE

Awareness: Risa Berrin was a health reporter for her college newspaper when she first started seeing how teens were unaware or misinformed about health and prevention.

She became part of the solution, starting a career as a certified human growth and reproductive health educator.

While teaching law classes at a Miami-area high school, she realized that teens were dealing with unaddressed health issues that could be taught in a fun and interactive way, just like the law classes she was teaching.

“I was highly aware that kids were not doing well, physically and emotionally and they were dealing with serious, serious issues… everything from obesity, to depression, to sexual assault and bullying,” Berrin said.

She wondered: Why was this happening?

Learn: Many U.S. schools don’t have funding for health teachers.

The few health teachers that are in schools may not have access to the latest health information, or have different standards of incorporating health education.

For example, public high schools in Miami-Dade County, Fla., discontinued health requirements for students in 2008, leaving only visiting health educators to come into schools as requested or for one-time events.

“In such a climate, students can be easily confused as to what to believe and where to find health resources and answers,” Berrin Said. Chronic disease, diabetes, and obesity disparities exist among youth of color in Miami-Dade County, where 66 percent of the population is Latino. Berrin believed that no matter what demographic or ethnicity reports show, all teens were dealing with a myriad of health issues.

“Lectures, text books, and the fear tactic model, did not have favorable outcomes,” Berrin said. “I was very saddened to see that kids were not in a good state, because they weren’t given a chance to make good decisions, and make decisions based on prevention, not just when they get into a crisis situation.”

“I realized that we really need to change this model and do something really different.”

Frame Issue: Berrin dreamed of improving the overall model of health education toward empowering students to get information and resources.

She wanted to start a new prevention-focused health education program.

“We [health educators] really needed to be more innovative,” Berrin said. “We really needed to give kids practical information so they can make better decisions.”

DEVELOPMENT

Education/Mobilization: To develop a thorough wellness program, Berrin started reviewing other health programs that had worked in smaller settings. She even traveled the country looking for programs to bring to Miami.

She couldn’t find a comprehensive, holistic, sustainable model.

“There were a lot of programs coming in and just doing a few days of bullying intervention, or suicide intervention, or obesity intervention, and these weren’t things that were being embedded into a school culture,” she said. “They weren’t systemic, like the entire district wasn’t embracing them…you can’t just separate nutrition and drugs from mental health, all of these things are very intertwined.”

“Positive peer pressure” is a key in delivering accurate, reliable health information, to empower people in making their own healthy choices with support of their peers, Berrin said.

She believed that, after examining other peer-based health models, similar peer modeling could work on a large scale in high-school settings.

“Whether it’s good behavior or bad behavior, you know peer pressure is something that is definitely realistic elements of high school life,” she said.

Debate:With an idea in place for a health education program, several obstacles remained—fleshing out the program and figuring out how to get schools to implement it.

ENACTMENT

Activation/Frame Policy:Berrin worked to develop her comprehensive health education program.

She called it the “Health Information Project (HIP).”

HIP seeks to empower students to adopt healthy lifestyles and prevention of disease using peer-led discussions in class. High school students in the junior and senior classes get trained as peer health educators (PHEs) to conduct interactive discussion sessions with their freshmen class peers.

These discussion sessions are based on a comprehensive health curriculum with these topics:

- Mental Health

- Reproductive Health

- Relationships

- Alcohol, Tobacco & Other Drugs

- Nutrition, Exercise & Obesity

- How To Be Healthy

“Students are aware of these health issues, they are able to help themselves, help each other, provide support,” Berrin said. “They are able to talk about it in a more tolerant environment, talk about if they are struggling with something, and they are reaching out and getting help.”

HIP also uses multimedia presentations, social marketing, health promotion activities, a website that helps connect kids to local health resources.

“That’s a big strength, is kids are proactively connecting to resources both on their school site, and the reputable site that they are connected to through the HIP program, and in their community and online,” Berrin said.

To lay the groundwork to bring HIP into schools, Berrin began working with Millie Fornell, who oversaw academics and transformation for Miami-Dade public schools. Fornell helped Risa to identify the right principals and schools that would embrace and pilot-test the HIP program.

Activation/Frame Policy: In February of 2015, HIP was presented by M-DCPS Superintendent Alberto Carvalho, to the school board and his administration, as a program he was supporting and incredibly enthusiastic about.

IMPLEMENTATION

Implementation: Berrin implemented HIP and started connecting students to local health resources—clinics, hospitals, parks, food and nutrition programs, and more—all in alignment with the topics peer health educators discuss in class.

The Miami-Dade HIP program is transforming the community, Berrin said.

“We have 11th and 12th graders that are leading this health movement in Miami to create change, not just for the students in their schools, but also for the adults and for the larger Miami community,” she said. “By focusing on making sure that kids are physically and emotionally healthy, we’re insuring that they are going to be successful academically and that we are going to create a

generation of civically engaged young people.”

Students take HIP lessons to their families, too, Berrin said.

“’You can’t continue to fry everything, we need to bake the chicken,’ or ‘bake the pork,” Berrin said students tell their mothers, thus enabling small, easy changes that they can achieve at school or at home.

Equity: HIP was developed to include students from multiple ethnicities, as many HIP schools have large Latino or African American populations.

“It’s been really cool for us to try it in so many places and see that it can be so successful,” Valerie said.

Sustainability: The program has expanded from two schools to more than 40 schools since its creation in 2009.

Valerie Berrin, Risa Berrin’s sister, came in to help HIP’s outreach to more schools in 2011. Valerie helped expand the program as well, since 2009, 50,000 high school students have been motivated and educated by HIP.

“You win them over by showing to them that it (HIP) is a successful program and that the model works,” she said.

HIP adapts easily to any school’s academic calendar by giving students leadership to have a sustainable healthy culture developed within each school’s community.

“The program that each school takes on is embedded within the schools culture, not dependent on outsiders coming in,” Valerie said.

HIP has been sustainable thanks to its peer health educators, Berrin said.

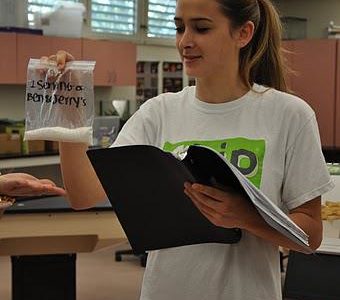

The educators train upcoming seniors and juniors to lead the next year’s incoming freshmen. They also have a HIP day (pictured at right) to bring all district peer health educators under one roof in one day to share the life-changing stories from their HIP participation.

“A lot of them really want to give back and help individuals at their schools, their peers,” Valerie said.

Working with local nonprofit organizations and companies for funding, the Berrin sisters plan to expand HIP to other districts and states if possible funding is provided.

By The Numbers

84

percent

of Latino parents support public funding for afterschool programs

This success story was produced by Salud America! with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The stories are intended for educational and informative purposes. References to specific policymakers, individuals, schools, policies, or companies have been included solely to advance these purposes and do not constitute an endorsement, sponsorship, or recommendation. Stories are based on and told by real community members and are the opinions and views of the individuals whose stories are told. Organization and activities described were not supported by Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and do not necessarily represent the views of Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.