Share On Social!

We know little about which transportation investments or initiatives are reducing transportation challenges and meeting people’s transportation needs.

For example, are Complete Streets policies meeting the needs of community members?

As Smart Growth America releases its best practices to evaluate the success of Complete Streets efforts, we at Salud America! want to draw attention to how transportation needs and barriers have been conceptualized.

Across the fields of urban planning, public health, and health care are claims about how transportation impacts health and quality of life. However, regarding these impacts, transportation is often conceptualized only in terms of physical activity, pollution, safety, and/or access to medical care.

Although transportation is often listed as a non-medical driver of health (NMDoH), rarely is it conceptualized in terms of barriers to employment security, economic security, and essential services and resources. And rarely is it conceptualized in terms of how it co-occurs with and/or exacerbates other NMDoH, such as food insecurity, unemployment, and material hardship.

It is because transportation needs and challenges have been poorly conceptualized and poorly operationalized (i.e., defined and measured), we know little about which transportation investments or initiatives are reducing transportation barriers and meeting people’s transportation needs and, in turn, improving health and quality of life.

Thus, we need urban planners to expand their understanding about how transportation impacts health and quality of life and push for better data collection on whether transportation investments and initiatives are meeting the needs of community members.

Why Should Urban Planning Stakeholders Care About Transportation as a Non-Medical Driver of Health?

Health is a complex phenomenon shaped by “the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life,” according to the World Health Organization.

These factors are known as non-medical drivers of health (NMDoH).

These factors are known as non-medical drivers of health (NMDoH).

“Neighborhood and Built Environment” is one of the five NMDoH domains.

The problem in the U.S. is that neighborhoods were not created equal.

Across the U.S., disconnected neighborhoods are overburdened by the concentration of poverty, underperforming schools, low food access, and unsafe, unreliable, unaffordable, and inadequate transportation.

These adverse neighborhood and built environment conditions contribute to problems in health outcomes, as well as issues in social and economic outcomes, which exacerbate issues in health.

Because urban planning practitioners, scholars, and leaders shaped and continue to shape these adverse conditions, urban planning stakeholders have a big role in shaping many of the social risk factors that are at the root of social, economic, and health issues.

Thus, urban planning stakeholders, particularly those developing and implementing Complete Streets policies, should care about transportation as a NMDoH.

How is Transportation as a NMDoH Conceptualized?

Most, if not all urban planning and public health scholars and practitioners, agree that transportation impacts social, economic, and health outcomes, even if they don’t use the term NMoH.

For example, transportation is almost always included in lists of examples of living conditions, along with housing, employment, income, and food access, that impact social, economic, and/or health outcomes.

Sometimes beyond being listed, transportation impacts are addressed in more detail, such as regarding physical activity, pollution, safety, and/or access to medical care.

However, rarely is transportation conceptualized in terms of barriers to employment security, economic security, and essential services and resources. And rarely is transportation conceptualized in terms of how it co-occurs with and/or exacerbates other NMDoH, such as food insecurity, unemployment, and material hardship.

There is no widely agreed upon concept of transportation needs/challenges, thus no widely agreed upon methods to measure transportation needs/challenges.

There is no widely agreed upon concept of transportation needs/challenges, thus no widely agreed upon methods to measure transportation needs/challenges.

Transportation needs/obstacles are often operationalized in terms of vehicle ownership, peak travel time reliability for commuters in single-occupancy vehicles, proximity to transit, or satisfaction with transportation.

These metrics fail to capture what is perhaps the most basic of all transportation performance questions, is public investment in transportation improving quality of life.

Vehicle ownership, for example, is often only measured in terms of number of household vehicles – often with no regard for the number of adults in the household or the financial burdens of operating and maintaining a vehicle.

Similarly, proximity to transit is often only measured in terms of distance to a transit route or transit stop – with no regard for the quality of transit service and the burdensome tradeoffs associated with dependence on transit, particularly in cities where transit is operated as a social safety net for disadvantaged populations, marked by infrequent service that is limited on evenings and weekends.

Transportation needs/challenges have yet to be conceptualized in terms of tradeoffs people are making to adapt to unsafe, unreliable, unaffordable, and inadequate transportation. They miss when people forego trips to essential destinations and skip spending on essentials.

In addition to the lack of consensus on how to conceptualize and operationalize transportation needs/challenges, there is also lack of consensus on how to conceptualize and operationalize the adverse living conditions at the root of transportation needs/barriers, such as unsafe, unreliable, unaffordable, and inadequate transportation.

Root causes of inadequate transportation are sometimes conceptualized in terms of incompatible values and goals; poor design practices and standards; lack of investment; inefficient investment; and the broader historical context and political economic factors behind vehicle dependence that threaten safety and access to options.

Even across the travel-built environment literature, there is lack of consensus on determining whether transit service levels are sufficient or insufficient.

One example demonstrates why this is such a stark omission in urban planning research.

In urban planning scholarship, there is evidence-based consensus on the threshold at which residential and employment density are supportive of transit ridership or not. But there is little evidence and little consensus on threshold at which the quality of transit service is sufficient for people to meet their transportation needs without burdensome tradeoffs.

How is Transportation as a NMDoH Operationalized?

While there has been a lot of effort to understand needs and challenges elated to housing instability and low food access as social risk factors that contribute to health-related social need, there has been little effort to understand needs and barriers related to inadequate transportation.

Food insecurity, for example, is a widely established concept in both the social sciences and social services, to include public health, social work, poverty reduction, and economic security programs.

In fact, food insecurity is an official term from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which they define as “a household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food” that results in reduced food intake and households being unable to meet their food needs.

National data on food insecurity have been collected annually since 1995. That information is used to inform over $100 billion in USDA annual spending on food and nutrition assistance programs and other public health and poverty reduction programs.

Contrast this with transportation.

There is no widely established concept of limited or uncertain access to adequate transportation that results in households being unable to meet their transportation needs.

The U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) does not collect annual data on if households are able to meet their transportation needs.

Below are brief summaries of some of the different ways inadequate transportation has been conceptualized and operationalized beginning with the major data collection effort conducted by USDOT Federal Highway Administration.

National Household Travel Survey. The National Household Travel Survey (NHTS), the only national source of personal travel data collected by USDOT, focuses on travel behavior. It does not measure if people are able to meet their transportation needs.

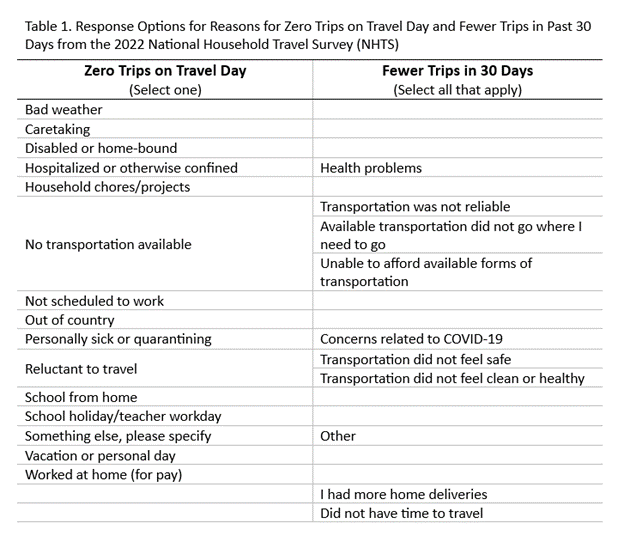

Unlike the previous NHTS in 2017, the most recent NHTS in 2022 asked people to share reasons why they didn’t travel (i.e., took zero trips on the day of the survey) and why they traveled less (i.e., took fewer trips in the past 30 days).

However, the questions are unable to capture if and why people skipped trips that they needed to take.

Moreover, the response options for the two questions do not align.

For example, for the question about zero trips on the survey day, the only response option related to transportation barriers is, “no transportation available.” For the question about fewer trips in the past 30 days, five response options were related to transportation barriers: transportation was not reliable, available transportation did not go where I need to go, unable to afford available forms of transportation, transportation did not feel safe, and transportation did not feel clean or healthy.

See Table 1. to compare response options for each of these questions.

See Table 1. to compare response options for each of these questions.

When survey questions and response options are unclear, the results are uninterpretable, incorrect, and/or embedded with hidden assumptions.

In short, the primary source of personal transportation data across the country only captures how, when, and why people travel; it does not capture if or why people are unable to meet their transportation needs. The data collected from these responses are insufficient to inform the nearly $100 billion in USDOT annual spending.

Transportation Insecurity. While a new set of measures was recently developed and validated by sociology scholars to assess a concept they coined as transportation insecurity, the tool assesses the experiences of inadequate transportation (e.g., being late, skipping trips, and worrying). But is does not assess sources of inadequate transportation (e.g., unreliable vehicle, insufficient transit, and transportation cost burden).

For example, one item in the tool is “In the past 30 days, how often were you late getting somewhere because of a problem with transportation?”, with responses options of “Often/Sometimes/Never.”

Measures of transportation problems like these are unable to inform stakeholders about the source of the transportation problem, thus are unable to inform stakeholders about needed interventions.

Social Need/Risk Screening Tools. Because NMDoH are significantly associated with health outcomes, there are a growing number of initiatives to screen for and address social risk/needs within the health care system, such as efforts in Texas, Pennsylvania, and community health centers across the country.

NMDoH screening can help shed light on transportation problems.

For instance, one study explored the relationship between health-related social needs and hospital stays and emergency department visits for over 56,000 Medicare Advantage beneficiaries.

The study found unreliable transportation had the largest significant association with increased hospital stays and emergency department visits compared to other health-related social needs (i.e., financial strain, housing insecurity, poor housing quality, food insecurity, utility insecurity, and loneliness).

Similarly, according to another study, transportation problems were the only social need significantly associated with chronic illness diagnosis among respondents at a federally qualified health center.

Although these findings are very important for understanding transportation as a NMDoH, the screening tools vary widely in their conception of transportation problems.

What does unreliable transportation mean, and how should urban planners address it?

These tools also lack psychometric evidence to evaluate validity and reliability.

In a content analysis of transportation specific questions in 23 social need screening tools, health scholars concluded: “It is clear there is not yet a single standard measure for either screening or for comprehensively assessing transportation needs and resources.”

The problem of lacking methods to measure transportation needs and barriers is found in urban and transportation planning, too.

Other Travel Behavior Surveys. Local transportation needs assessments often focus on travel behavior, satisfaction with transit, and other measures of comfort.

They rarely measure needs and barriers.

The Illinois Department of Transportation, for example, conducts its annual Traveler Opinion Survey to help “record and track performance and public satisfaction levels on a variety of transportation issues.”

The problem with measuring satisfaction is it is a measure from the private sector rather than the public sector. There is an important distinction between whether a private industry is meeting consumers’ satisfaction for a commodity and whether a government agency is improving quality of life through public spending.

Imagine if the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services only measured patient satisfaction rather than patient outcomes.

Regarding transit specifically, customer satisfaction fails to represent the quality of transit service provided, according to a study proposing methodology for measuring transit service quality and a study proposing methodology for measuring multimodal quality of service.

While satisfaction does vary in a plausible way and is affected by changes in transit service, such as access to bus stops and bus travel time, there is no evidence that satisfaction is fully representative of quality or of people’s ability to meet their transportation needs.

Transportation Performance. Even more progressive transportation policies and practices, like Complete Streets and performance-based planning and programming, lack the methodology to measure if transportation investment is reducing barriers and meeting people’s transportation needs.

Performance-based planning, for example, often focuses on reducing vehicle delay. This results in the investment of hundreds of millions of dollars in U.S. communities to shave a few minutes off peak vehicle commute time, despite that transit commute times are often nearly double vehicle commute times.

While Complete Streets efforts focus on improving safety, reducing vehicle travel, and increasing physical activity, they often do so without assessing if people can meet their transportation needs without burdensome tradeoffs.

These examples demonstrate that transportation performance has been poorly conceptualized and operationalized.

What Do We Do Next?

First, check out Smart Growth America’s new guide, From Policy to Practice: A Guide to Measuring Complete Streets Progress.

Second, we need to acknowledge how poorly we have conceptualized transportation as a SDoH, then push for a more comprehensive conceptualization of transportation as a NMDoH beyond physical activity, safety, and pollution.

We need to acknowledge this every time we discuss the intersection between transportation and health.

Third, we need to acknowledge the lack of understanding about whether transportation investments are reducing challenges and helping people meet their transportation needs, then push for a better understanding about transportation needs/barriers.

We need to acknowledge this across all levels of transportation planning, decision-making, and investment.

Fourth, we need to develop and validate a set of measures to assess transportation needs/challenges that can be used across urban planning and public health practice and scholarship.

Like low food access and food insecurity, we need to establish inadequate transportation as a social risk factor that contributes to health-related social need.

To realistically assess Complete Streets performance, we need a validated set of measures to assess transportation needs/challenges.

Only when people are able to meet their transportation needs without burdensome tradeoffs can our streets be truly complete.

Explore More:

Transportation & MobilityBy The Numbers

27

percent

of Latinos rely on public transit (compared to 14% of whites).