Share On Social!

At her annual wellness visit, Dr. Stormee Williams filled out a digital questionnaire that asked about her need for help with housing, transportation, food access, and other non-medical needs.

Williams was taking an “SDoH Screener.”

An SDoH screener is a questionnaire to help healthcare workers identify a patient’s issues with the social determinants of health (SDoH), the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of social, economic, and political systems that shape life.

If a screener finds a patient in need, healthcare workers can then connect the patient to community support and resources. Helping patients address these non-medical needs can help them achieve better health.

Williams, fortunately, didn’t have non-medical needs.

But filling out the SDoH screener planted a big idea in Williams, a pediatrician and vice president and chief health equity officer of Children’s Health, the largest pediatric health system in North Texas.

“I was like, wait a minute, we can do this,” Williams said.

She wanted to bring an SDoH Screener to Children’s Health. But how could she accomplish it?

SDoH Issues Impact People’s Health

As a pediatrician, Williams already knew that SDoH issues play a huge role in health.

Adverse living conditions, such as underperforming schools, food deserts, and unsafe or inadequate transportation, contribute to inequities in health, social, and economic outcomes.

Unsafe transportation, for example, is a social risk factor that can directly impact health through exposure to traffic crashes and air pollution, and inadequate transportation is a social risk factor that can directly impact health through access to medical care and medications. Inadequate transportation can also indirectly impact health through access to jobs, food, education, and other resources and opportunities.

“I could write a prescription for a patient who has asthma to get asthma medication, but if the mom doesn’t have transportation to the pharmacy to pick up that prescription or money to pay for that, then it doesn’t matter,” Williams said.

So, when Williams was taking an SDoH screener at her own doctor’s visit in 2021, she took note.

She learned her doctor’s clinic embedded the screener in its electronic health record system. This made it easier to identify social needs in patients and make referrals to community resources, rather than clinic staff having to do manual question-and-answer sessions during a patient visit.

“Because social risk factors disproportionately impact underserved communities, promoting screening for these factors could serve as evidence-based building blocks for supporting hospitals and health systems in actualizing commitment to address disparities, improve health equity through addressing the social needs with community partners, and implement associated equity measures to track progress,” according to a 2022 final rule from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Williams also learned that her clinic used the same electronic health record system, EPIC, used at Children’s Health System of Texas.

She believed SDoH screening could benefit Children’s Health, which has about 430,000 outpatient visits, 20,000 inpatient admissions, and 170,000 emergency visits a year, in addition to dozens of specialty ambulatory clinics providing services to a racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically diverse patient population, according to a 2023 report.

So Williams brought the idea to the chief technology officer at Children’s Health.

Piloting an SDOH Screening Program at Children’s Health

Williams learned that Children’s Health had piloted a SDOH screening program in four sites in 2019.

But the program was terminated during COVID-19.

With an emphasis on quality improvement, the pilot program included an SDOH screening tool; baseline and ongoing training for clinical care teams; and patient referrals to community resources.

Williams was excited to learn that during the pilot program, the SDOH screening tool was embedded in their EPIC electronic health record system.

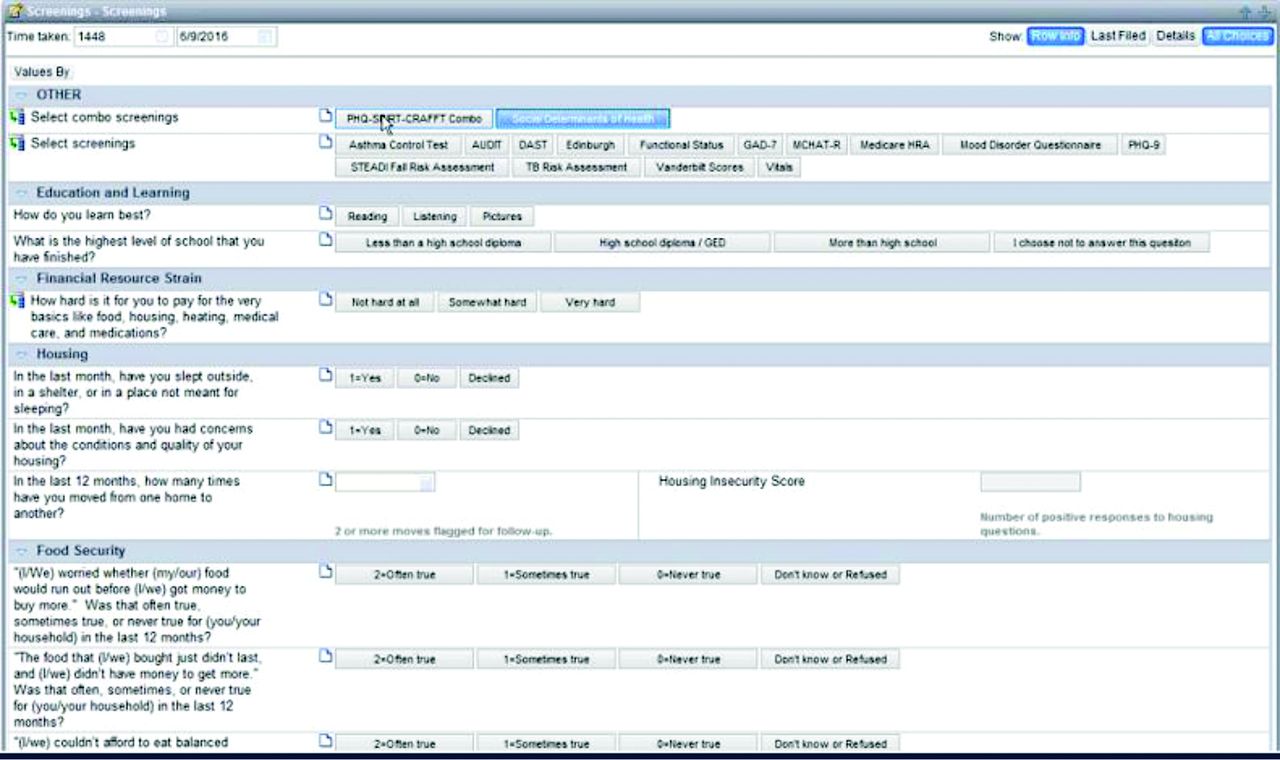

In fact, EPIC already had a 9-question SDOH screening tool as an existing feature in the system.

That means that Williams and her equity team would not have to create a questionnaire and the technology team would not have to make any major changes within EPIC.

Rather, they could simply activate the existing feature.

“We actually do have the capability to do this,” Williams said.

And she was already thinking big.

“We have to move this into an entire-system project and not just in these pilot areas,” Williams said.

However, implementing new programs is challenging, particularly in healthcare settings because COVID-19 triggered a mass exodus of healthcare staff and fatigue among those remaining.

That’s why the initial 2019 pilot program is so interesting.

It wasn’t just a pilot program to assess and address patient’s social needs.

Rather, researchers wanted to conduct a longitudinal research study about the quality improvement component of the SDOH screening program.

They wanted to learn about the implementation of SDOH screening programs within clinics.

A Study of the Pilot SDOH Screening Program at Children’s Health

To understand factors that impact implementation of SDOH screening programs, researchers selected four Children’s Health sites that treat medically complex children and adolescents to conduct their three-pronged pilot program in 2019: baseline and ongoing training for clinical care teams; an SDOH screening tool embedded in EPIC; and providing in-need patients a sheet of community resources.

Medically complex pediatric patients often encounter unique barriers to care and non-medical needs.

For example, an average of “54% of medically complex children’s caregivers stop working because of their child’s healthcare needs,” according to a 2020 study about the pilot program. “This disrupts a family’s financial stability, leading to challenges in timely insurance and medical payments.”

The pilot intervention began with SDOH trainings for healthcare teams at the four sites.

Regarding data collection, the researchers administered baseline, 1-month, and 3-month surveys to clinical care teams at the four pilot sites about confidence to discuss SDOH, knowledge of SDOH, and knowledge for advising families on community resources.

They also administered focus groups to clinical care teams about satisfaction with the SDOH screening implementation, integrated care workflows and tasks within the screening areas, and the culture of clinical organization.

While screening rates differed across the four sites, an average of 74% of 506 medically complex pediatric patients were screened for SDOH, according to a 2020 study about the pilot program.

Among the sample of those screened, nearly half reported at least one health-related social need.

There were no statistically significant differences in positive screenings across the four sites. However, the rates of providing community resource sheets also differed across the four sites, with an average of 62% of patients who screened positive receiving a community resource sheet, ranging from 20% to 91%, according to the study.

These differences demonstrate that implementation can vary across sites, which supports the need to understand challenges in implementation at the clinic level.

The study authors conclude that differential success across the four sites was likely due to three themes:

- ability to integrate the SDOH screener into the differing workflows of the implementers (e.g., nurse, social workers, or case manager);

- differing time constraints of the operational workflows at different sites (e.g., outpatients vs. inpatient settings); and

- individual characteristics of the implementers (e.g., knowledge about and confidence to discuss health-related social needs, which are related to their licensure and training experience).

Although the study found there were no statistically significant changes in clinical staffs’ knowledge of SDOH, confidence to discuss SDOH, and knowledge for advising families on community resources at three months post-implementation compared to baseline, baseline confidence and knowledge matter and different depending on licensure and training experience of different staff, which social workers having higher knowledge about and confidence to discuss SDOH than nurses.

“For example, the high levels of success [at one pilot site] was due to social workers using their experience to use the screener as a conversation guide about positive answers,” the study states. “In addition, implementers with a social work background also had a solid knowledge base of community-based organizations.”

These findings are relevant for everyone interested in SDOH screening programs in healthcare systems – which included Williams and many others across the nation.

SDOH Screening Continues to Gain National Momentum

Amid Williams’ interest and the pilot program at Children’s Health, national momentum was building toward assessing and addressing non-medical needs in the healthcare system.

Nemours Children’s Health began developing their SDoH Screener in 2018.

In addition, the National Association of Community Health Centers has spent years helping community health centers (also called Federally Qualified Health Centers) conduct SDoH screening to identify social needs in patients and refer them to local aid and resources.

“The American College of Physicians, National Academy of Medicine, and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force all recommend routine SDOH screening as a standard part of preventive care,” according to the 2020 publication about the Children’s Health 2019 pilot SDOH screening program.

As for SDoH screening tools themselves, many different screeners exist. Each may ask different questions, have some limitations, and many are often not scientifically tested. However, support and usage of SDoH screening tools continues to grow.

For example, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) had recently passed final rules calling for SDoH screening in through Special Needs Plans (SNPs) and the Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR) Program. Read more about this here. Of note, CMS refers to SDOH as health-related social need (HRSN).

Accreditation bodies, like the Joint Commission that accredits and certifies over 22,000 health organizations, were considering requiring SDOH screenings.

In June 2022, the Joint Commission set new requirements to reduce health care disparities for “organizations in the Joint Commission’s ambulatory health care, behavioral health care and human services, critical access hospital, and hospital accreditation programs,” which include SDOH screening.

The exact Joint Commission requirement is “the [organization] assesses the [patient’s] health-related social needs and provides information about community resources and support services.” Of note, the Joint Commission refers to SDOH as health-related social need (HRSN). Read about this here.

Williams knew these conversations were happening and knew it was important for health systems to take the lead.

“We cannot continue to fight healthcare issues with just healthcare alone,” Williams said. “We have to, at a bare minimum, inquire about barriers that are keeping our patients from reaching their optimal levels of health, and [SDoH screening] is one of those great tools that allows us to do that.”

Launching the SDoH Screening Program at Children’s Health

Before either CMS or the Joint Commission set their requirements, Williams organized a team with information services and healthy equity staff members in 2021.

They met weekly to discuss a comprehensive SDoH screening program at Children’s Health.

They considered findings from the 2019 pilot study and spoke with many clinicians, particularly those concerned about an additional stressor to health care staff since COVID-19.

“We cannot put another stressor on our bedside staff,” Williams said.

After a few months, Williams and her team launched the SDoH screening program in July 2022.

Rolling Out the SDoH Screening Program at Children’s Health

Forest Melton, who had recently joined Children’s Health as Health Equity Program Manager, attended the meetings that led up to the launch of the SDoH screening program.

Melton supports training efforts across clinics and understands that the workflows are different depending on the clinic setting.

With this in mind, Williams, Melton, and their team trained staff in and rolled out the SDOH screening program in two to four clinics at a time.

For the trainings, they created presentations and speeches using information from multiple sources like the CDC and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. They also worked with their internal learning and development institute to create videos and a full curriculum.

Throughout the implementation process, they had quality improvement advisors as part of the program.

They would work out the kinks before moving on to other clinics.

The SDoH screener at Children’s Health includes 12 questions covering food insecurity, housing insecurity, transportation insecurity, digital insecurity, utilities insecurity, health literature, social support, and tobacco exposure and use. It takes three to five minutes to complete.

The patient’s parent or guardian is asked to complete the SDOH survey during electronic check-in using the patient electronic web portal. They are asked to fill it out twice a year.

“If the survey has not been completed at the time of arrival to the clinic visit, registration staff see an indicator showing this in the [electronic health record] and provide the parent or guardian a tablet for completion of the SDOH survey, as well as any other relevant clinical questionnaires (varying by clinic),” according to a 2023 report.

Clinic staff are alerted when a patient screens positive for a health-related social need and are provided a list of community resources to give to the patient.

If a patient screens positive for a high-risk health-related social need, which they define as housing food, housing, and utilities insecurity, designated social work staff members follow up with these patients.

Williams’ team also created a reporting system to draw data directly from the electronic health record to report SDOH survey completion rates by clinic as well as community referral rates.

This helps them target which clinics need follow-up trainings.

Now, Children’s Health is screening families at nearly 100 sites, most of which are ambulatory sites and the rest inpatient sites.

Nearly 75,000 patient families completed the SDOH screening from January 2023 to December 2023, which is roughly 29% of their families.

“This work is important because health outcomes rely on so much other information beyond just health care,” Williams said.

“The people that need help the most are who we are impacting the greatest,” Melton said.

Williams and her team continued to meet weekly for the first year and then began meeting monthly.

Melton still attends these meetings to update the SDoH screener and work with clinicians to ensure a smooth process implementing the screener.

A Grateful Patient and a Grateful Clinician

Williams likes to share a story of a patient who expressed gratitude for the screening program.

“We had a family that responded “yes” to just about every need in the questionnaire, and we were able to connect them with a social worker who provided immediate, in-hand resources,” Williams said.

The patient was grateful that she was asked these questions because she got the help she needed in an unexpected place.

“She didn’t think she would go to her doctor’s visit and get help for food and the other needs she had,” Williams said of the patient.

What is particularly interesting about this story is that the patient was visiting a clinic that initially hesitated to be part of the screening program.

The clinic is located in an affluent part of town. The clinic team thought that, because their patients lived in an affluent part of town, they wouldn’t face barriers to staying healthy and thus wouldn’t need the questionnaire about their social needs.

Williams encouraged them to implement the screening anyway, and they did so.

After this patient screened positive for almost all of the social needs, a staff member at the clinic reached out to Williams to express gratitude for the social need screening program because it helped improve patient care.

Many clinicians have since realized that an SDoH screener is an important diagnostic tool in the healthcare setting. It helps care teams identify and address health-related social needs that they otherwise would not have known about.

To be clear, Children’s Health received zero funding for the pilot and research study in 2019 and zero funding to launch the full program in July 2022.

To this point, Williams acknowledged the need for payers to reimburse for social need screenings, to include Medicare and Medicaid and commercial payers.

What’s Next for Williams and Children’s Health?

Melton continues working to get community resources automated to close the referral loop.

He and Williams know there is a moral burden on staff to ask families difficult questions about their social needs without being able to directly connect them resources and without knowing if they get access to those resources.

“It’s not just about collecting answers, even though that is huge for us,” Williams said. “We want to connect our families to resources.”

“We want to make sure every single social need is being addressed,” Melton added.

Currently, the social work team at each screening site updates the list of community resources in their electronic health record system. After all, social workers tend to have more geographically sensitive, community-based connections.

From this massive list, they can pull up the nearest community group to help families meet their needs.

Children’s Health currently has no funding or personnel to track if patients utilized the referrals.

Thus, Williams and her team are working on partnerships with community organization and companies that offer resource referrals to both increase patient’s access to referrals and to integrate referral into their electronic health record.

If referrals are integrated into their electronic health record, staff can track whether a family is actually getting the resources they need and seeing results.

The team also continues to refresh training materials as they continue to roll out screening at more sites.

They attend and present at conferences, commissions, and consortiums, like the Children’s Hospital Association Conference, the Joint Commission, and the new Texas Consortium for the Non-Medical Drivers of Health.

Williams and Melton are also still trying to get more sites to adopt the SDOH screening program.

They hope that, by the end of 2024, they are screening 60% of their families.

“If I can help one family in this massive effort, then it makes it all worthwhile,” Williams said.

By The Numbers

142

Percent

Expected rise in Latino cancer cases in coming years

This success story was produced by Salud America! with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The stories are intended for educational and informative purposes. References to specific policymakers, individuals, schools, policies, or companies have been included solely to advance these purposes and do not constitute an endorsement, sponsorship, or recommendation. Stories are based on and told by real community members and are the opinions and views of the individuals whose stories are told. Organization and activities described were not supported by Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and do not necessarily represent the views of Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.