Share On Social!

James Rojas loved how his childhood home brought family and neighbors together.

The L.A. home had a big side yard facing the street where families celebrated birthdays and holidays. Uncles played poker. Aunts tended a garden. Children roamed freely. Mexican elders—with their sternness and house dresses—socialized with their American-born descendants—with their Beatles albums and mini-skirts.

Rojas was shocked to find some would look down on this neighborhood.

“Why do so many Latinos love their neighborhood so much if they are bad?” he wondered.

Rojas, in grad school, learned that neighborhood planners focused far more on automobiles in their designs than they did on the human experience or Latino cultural influences.

He wanted to change that.

Rojas has spent decades promoting his unique concept, “Latino Urbanism,” which empowers community members and planners to inject the Latino experience into the urban planning process.

Side Yard a Key to Latino Neighborhood Sociability, Family Life

Rojas grew up in the East L.A. (96.4% Latino) neighborhood Boyle Heights.

His extended family had lived in their home on a corner lot for three decades. Many other family members lived nearby.

Like many Latino homes, the interior lacked space for kids to play. Beds filled bedrooms, and fragile, “beautiful little things” filled the living room.

The large side yard, which fronted the sidewalk and street, was where life happened.

“This side yard became the center of our family life—a multi-generational and multi-cultural plaza, seemingly always abuzz with celebrations and birthday parties,” Rojas said.

The yard was an extension of the house up to the waist-high fence that separated private space from public space, while also moving private space closer to public space to promote sociability.

“Like a plaza, the street acted as a focus in our everyday life where we would gather daily because we were part of something big and dynamic that allowed us to forget our problems of home and school,” Rojas wrote in his 1991 thesis.

Then it all disappeared.

Displacement Underscored the Unique Aspects of Latino Neighborhoods

In the 1970s, the local high school expanded. It required paving over Rojas’ childhood home, displacing his immediate and extended family.

“It was like an unexpected family death, except there was no funeral, eulogy, or reflection on how this place had shaped us,” Rojas wrote in 2016.

His grandmother’s new home, a small Spanish colonial revival house, sat on a conventional suburban lot designed for automobile access, with a small front yard and big backyard.

“Gone was the side yard that brought us all together and, facing the street, kept us abreast with the outside world,” Rojas wrote.

While being stationed with the U.S. Army in Germany and Italy, Rojas got to know the residents and how they used the spaces around them, like plazas and piazzas, to connect and socialize. This led Rojas to question and study American planning practices.

Planners Were Wrong About What East L.A. Neighborhoods Needed

Rojas pursued master’s degrees in architecture studies and city planning at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

He wanted to better understand how Mexicans and Mexican Americans use the places around them.

During this time, he came across a planning report on East Los Angeles that said, “it lacks identity…therefore needs a Plaza.”

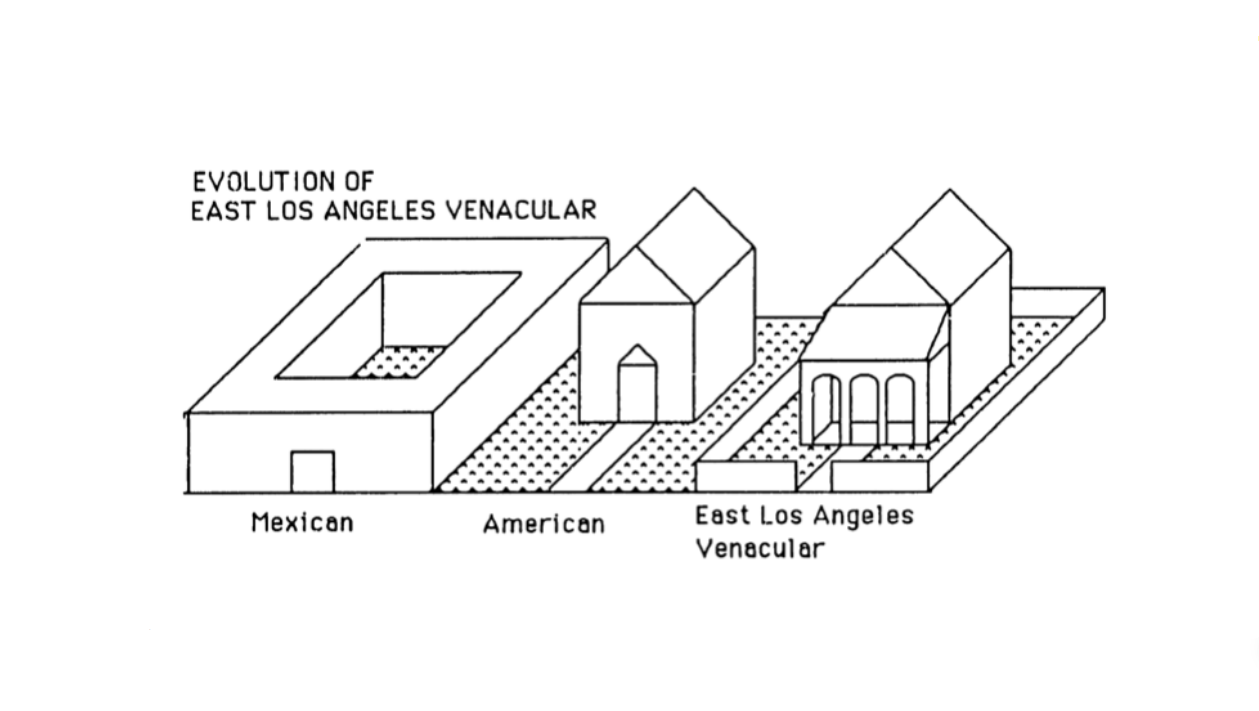

He recognized that the street corners and front yards in East Los Angeles served a similar purpose to the plazas in Germany and Italy. By combining both these “plazas” and the “courtyards” of Mexico, residents created places for people to congregate in their own neighborhood.

These places absolutely created identity.

The planners were wrong about needing a separate, removed plaza.

“My understanding of how urban landscapes function is a product of the visual and spatial landscape my family created on the corner lot of my childhood home,” Rojas said.

In 1991, Rojas wrote his thesis about how Mexicans and Mexican Americans transformed their front yards and streets to create a sense of “place.”

“Planners develop abstract concepts about cities, by examining numbers, spaces, and many other measures which sometimes miss the point or harm [existing Latino] environments,” Rojas wrote in his thesis.

How could he help apply this to the larger field of urban planning?

Rojas’ Critiques About American Urban Planning

Rojas found that urban planners focus too much on the built environment and too little on how people interact with and influence the built environment.

For example, planners focused on streets to move and store vehicles rather than on streets to move and connect people.

“Thinking about everything from the point-of-view of the automobile is wrong,” Rojas said. “Particularly in neighborhoods.”

Planners have long overlooked benefits in Latino neighborhoods, like walkability and social cohesion.

Social cohesion is the degree of connectedness within and among individuals, communities, and institutions.

“Social cohesion is the number one priority in Latino neighborhoods,” Rojas said.

But in the 1990s, planners weren’t asking about or measuring issues important to Latinos. Latinos weren’t prepared to talk about these issues, either.

But in the 1990s, planners weren’t asking about or measuring issues important to Latinos. Latinos weren’t prepared to talk about these issues, either.

That meant American standards couldn’t measure, explain, or create Latino’s experiences, expressions, and adaptations.

“Unlike the great Italian streets and ‘piazzas” which have been designed for strolling, Latinos [in America] are forced to retrofit the suburban street for walking,” Rojas later wrote. “Instead of admiring great architecture or sculptures, Latinos are socializing over fences and gates.”

Latino Urbanism Transforms and Sustains the Neighborhood Street

Rojas wanted to create a common language for planners and community members.

So, he came up with Latino vernacular, which morphed into “Latino Urbanism.”

When Latino immigrants move into traditional U.S. suburban homes, they bring perceptions of housing, land, and public space that often conflict with how American neighborhoods and houses were planned, zoned, designed, and constructed.

For example, unlike the traditional American home built with linear public-to-private, front-to-back movement from the manicured front lawn, driveway/garage, and living room in the front to bedrooms and a private yard in the back, the traditional Mexican courtyard home is built to the street with most rooms facing a central interior courtyard or patio and a driveway on the side.

American lawns create psychological barriers and American streets create physical barriers to Latino social and cultural life.

Latino Urbanism adds elements that help overcome these barriers.

Fences, porches, murals, shrines, and other props and structural changes enhance the environment and represent Latino habits and beliefs with meaning and purpose.

In an essay, Rojas wrote that Latino single-family houses communicate with each other “by sharing a cultural understanding expressed through the built environment.”

“The residents communicate with each other via the front yard. By building fences, they bind together adjacent homes. By adding and enlarging front porches, they extend the household into the front yard. These physical changes allow and reinforce the social connections and the heavy use of the front yard.

“The entire street now functions as a ‘suburban’ plaza where every resident can interact with the public from his or her front yard. Thus, Latinos have transformed car-oriented suburban blocks to walkable and socially sustainable places.”

Rojas was alarmed because no one was talking about these issues.

Planners Weren’t Asking and Latinos Weren’t Articulating

As a planner and project manager for Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transit Authority who led many community workshop and trainings, Rojas found people struggled to discuss their needs with planners.

“A lot of urbanism is spatially focused,” Rojas said. “It is difficult to talk about math and maps in words.”

Additionally, planning is a male-dominant environment.

Rojas thought they needed to do more hands-on, family-friendly activities to get more women involved and to get more Latinos talking about their ideals.

Overall, Rojas felt that the planning process was intimidating and too focused on infrastructure for people driving. It ignored how people, particularly Latinos, respond to and interact with the built environment.

For example, he thought that Latinos and street vendors did more for pedestrian safety and walkability than the department of transportation.

These informal adaptations brought destinations close enough to walk and brought more people out to socialize, which slowed traffic, making it even safer for more people to walk and socialize.

“Immigrants are changing the streets and making them better,” Rojas said.

Helping Latinos, Planners Create Better Communities

Rojas wanted to help planners recognize familiar-but-often-overlooked Latino contributions and give them tools to account for and strengthen Latino contributions through the planning process.

He also wanted to help Latinos recognize these contributions and give them the tools to articulate their needs and aspirations to planners and decisionmakers.

To bring Latino Urbanism into urban planning, Rojas founded the Latino Urban Forum in 2005.

The Latino Urban Forum is a volunteer advocacy group dedicated to improving the quality of life and sustainability of Latino communities.

A few years later Rojas founded an interactive planning practice to promote Latino Urbanism.

Engaging the Community in Urban Planning and Advocacy

Rojas founded PLACE IT! in 2011 to help engage the public in the planning and design process.

Through art-based three-dimensional modeling and interactive workshops, PLACE IT! provides a comfortable space to help community members understand and discuss the deeper meaning of place and mobility.

“Artists communicate with residents through their work by using the rich color, shapes, behavior patterns, and collective memories of the landscape than planners,” Rojas said. “Urban planners use abstract tools like maps, numbers, and words, which people often don’t understand.”

Activities aim to make planning less intimidating and reflect on gender, culture, history, and sensory experiences.

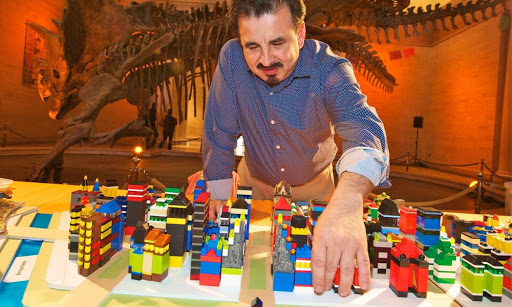

For example, in one workshop, participants build their favorite childhood memory using found objects, like Legos, hair rollers, popsicle sticks, pipe cleaners, buttons, game pieces and more.

These activities give participants a visual and tactile platform to reflect, understand, and express themselves in discussing planning challenges and solutions regardless of language, age, ethnicity, and professional training.

“I give them a way to understand their spatial and mobility needs so they can argue for them,” Rojas said.

Rojas also organizes trainings and walking tours. He lectures at colleges, conferences, planning departments, and community events across the country.

Through these activities, Rojas has built up Latinos’ understanding of the planning process so they can continue to participate at the neighborhood, regional, and state levels for the rest of their life.

He has also grown a following.

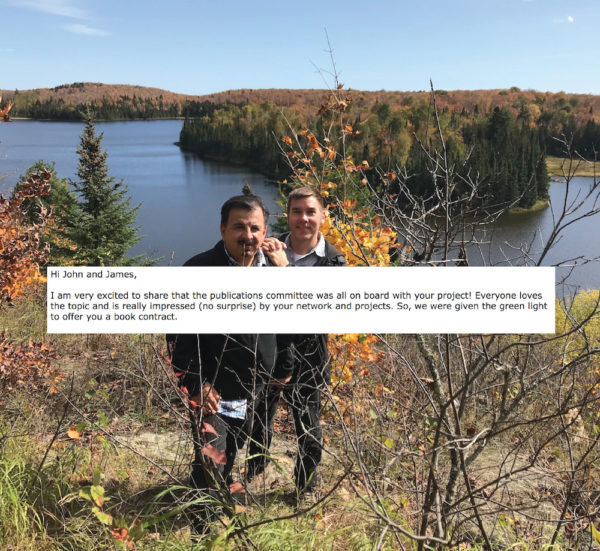

For example, 15 years ago, John Kamp, then an urban planning student, heard Rojas present.

Kamp has been partnering with him since.

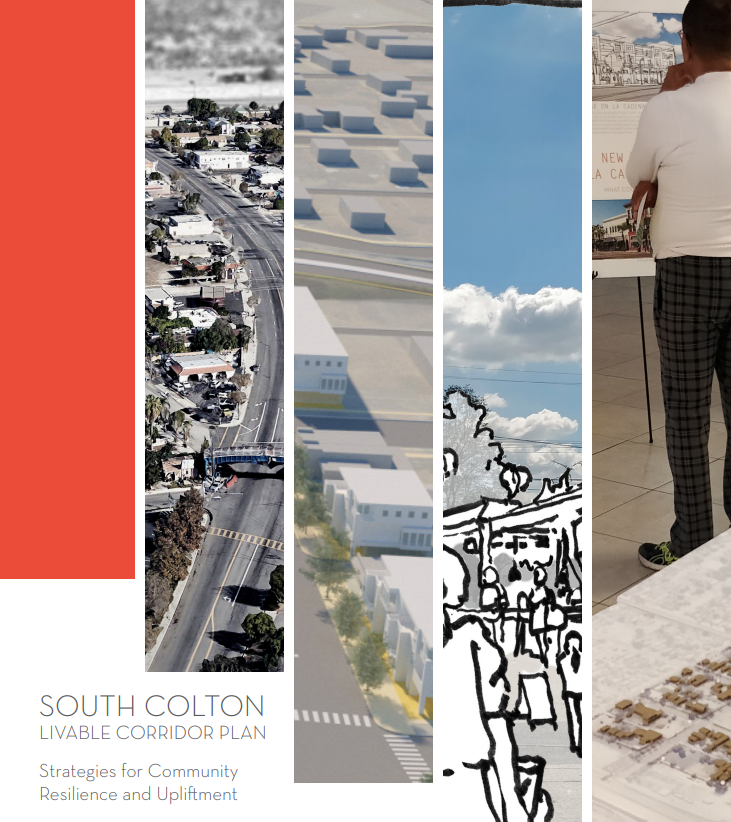

In 2018, Rojas and Kamp responded to a request for proposal by the Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG) to prepare a livable corridor plan for South Colton, Calif. They gained approval as part of a team of subcontractors.

The South Colton Livable Corridor Plan and Latino Urbanism

Colton, Calif. (69.3% Latino) was hit hard by poor transportation and land use decisions.

Five major forms of transportation infrastructure, like highways and freight lines, surround and bisect the city, cutting South Colton off physically, visually, and mentally.

“South Colton was the proverbial neighborhood on ‘the wrong side of the tracks,’” according to South Colton Livable Corridor Plan.

Wide roads, vacant lots, isolation and disinvestment have degraded the environment, particularly for people walking and biking.

“Over the years however, Latino residents have customized and personalized these public and private spaces to fit their social, economic, and mobility needs,” according to the livable corridor plan.

Rojas and Kamp wanted to start with these positive Latino contributions.

“We want to give a better experience to people outside their cars,” Rojas said.

To learn about residents’ memories, histories, and aspirations, Rojas and Kamp organized the following four community engagement events, which were supplemented by informal street interviews and discussions:

- Kickoff workshop at the El Sombrero Banquet Hall with a variety of hands-on activities to explore participants’ childhood memories as well as their ideal community;

- Pop-up event at Sombrero Market to explore what participants liked about South Colton and problems they would like fixed;

- Walking tour beginning at Rayos De Luz Church to explore, understand, and appreciate the uniqueness of the neighborhood; and

- Open house at the El Sombrero Banquet Hall to explore ideas and concepts for hypothetical improvements.

“We want participants to feel like they can be planners and designers,” Kamp said. “Everyone has those skills in them, but it’s hard to be aspirational and think big at the traditionally institutional meetings.”

They used the input from these events, along with key market findings, to develop the South Colton Livable Corridor Plan, which was adopted by Colton City Council in July 2019.

The recommendations in this document are essentially the first set of Latino design guidelines.

The recommendations in this document are essentially the first set of Latino design guidelines.

“This was the first time we took elements of Latino Urbanism and turned them into design guidelines,” Kamp said.

They are less prescriptive and instead facilitate resident’s do-it-yourself (DIY) or rasquache nature of claiming and improving the public realm.

Next Steps for Rojas and Latino Urbanism

Although Rojas has educated and converted numerous community members and decisionmakers, the critiques of the 1980s still remain today.

“It could be all Latinos working in the department of transportation, but they would produce the same thing because it is a codified ‘machine,’” Rojas said. “And dollars are allocated through that machine.”

For example, the metrics used to determine transportation impacts are often automobile-oriented and neglect walking, biking, and transit, thus solutions encourage more driving. Moreover, solutions neglect the human experience.

Rojas is pounding the pavement and working the long-game, one presentation at a time.

Rojas and Kamp recently signed a contract with Island Press to co-write a book on creative, sensory-based, and hands-on ways of engaging diverse audiences in planning.

“The overall narrative of the book will follow the South Colton project,” Kamp said.

It took a long time before anyone started to listen.

“It’s been an uphill battle,” Rojas said. “Like the Black Lives Matter and LGBTQ movements, Latino Urbanism is questioning the powers that be.”

Now, Latino Urbanism is increasingly common for many American planners.

“It’s a different approach for urban space,” Rojas said. “Latinos have something good. Now let’s make it better.”

READ MORE ABOUT JAMES ROJAS

- LAist:https://laist.com/2020/10/23/race_in_la_how_an_outsider_found_identity_belonging_in_the_intangible_shared_spaces_of_a_redlined_city.php

- Common Edge: https://commonedge.org/designers-and-planners-take-note-peoples-fondest-memories-rarely-involve-technology/

- Streetsblog USA: https://usa.streetsblog.org/2019/06/05/what-we-can-learn-from-latino-urbanism/

- KCET 2016: https://www.kcet.org/shows/lost-la/a-place-erased-family-latino-urbanism-and-displacement-on-las-eastside

- APA California Chapter Norther: http://norcalapa.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Latino-vernacular-is-transforming-American-streets.pdf?rel=outbound

- LA Taco: https://www.lataco.com/james-rojas-latino-urbanism/

- Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage: https://www.lataco.com/james-rojas-latino-urbanism/

- LA Great Streets: https://lagreatstreets.tumblr.com/post/116044977213/latino-urbanism-in-east-la-and-why-urban-planners

- KCET 2015: https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/why-urban-planners-should-work-with-artists

- Voices for Healthy Kids Action Center: https://www.voicesactioncenter.org/walking_while_latino_build_your_ideal_latino_street?utm_campaign=it_feb_27_20_5_nongmail&utm_medium=email&utm_source=voicesactioncenter

By The Numbers

27

percent

of Latinos rely on public transit (compared to 14% of whites).

This success story was produced by Salud America! with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The stories are intended for educational and informative purposes. References to specific policymakers, individuals, schools, policies, or companies have been included solely to advance these purposes and do not constitute an endorsement, sponsorship, or recommendation. Stories are based on and told by real community members and are the opinions and views of the individuals whose stories are told. Organization and activities described were not supported by Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and do not necessarily represent the views of Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.