Share On Social!

This is part of the Salud America! The State of Latino Early Childhood Development: A Research Review »

Latino Kids Start Developmentally Behind their Peers

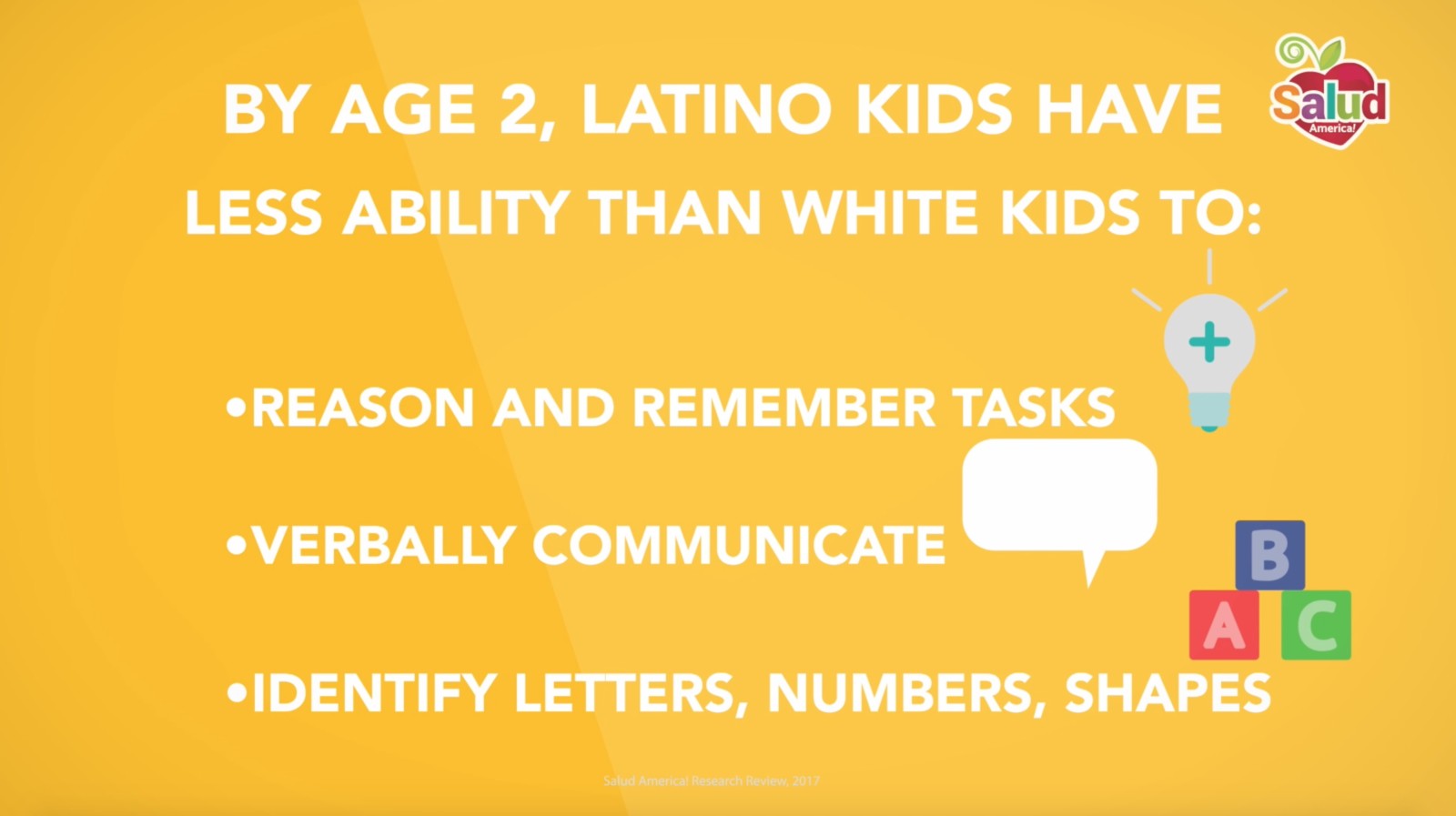

Although Latino children may be of similar weight at birth and equally able to thrive in the first 2 years of life compared with white children,96 their ability to reason and remember tasks (cognitive processing skills), verbally communicate, and identify letters, numbers, and shapes (preliteracy skills) lessens significantly by age 24 months, and these disparities appear even more prevalent in Mexican-American children than in other Latino subgroups.1

Although Latino children may be of similar weight at birth and equally able to thrive in the first 2 years of life compared with white children,96 their ability to reason and remember tasks (cognitive processing skills), verbally communicate, and identify letters, numbers, and shapes (preliteracy skills) lessens significantly by age 24 months, and these disparities appear even more prevalent in Mexican-American children than in other Latino subgroups.1

In general, a 15- to 25-percentage point gap exists for Latino children relative to their white peers.97 Children who start behind in kindergarten often stay behind. See more in the full Salud America! research review on building support for Latino families.98

Causes for cognitive, preliteracy, and oral communication gaps in Latino children are multifactorial.

Among the most common are poor education, large family sizes, low employment or having multiple jobs, and depression among Latina mothers. These factors have been suggested to reduce the likelihood that Latino parents would engage their children in preliteracy activities or read books to them, both very important activities leading to literacy and school readiness.1,99,100

Although most Latino parents are bilingual or can speak English fairly well, some do not have a good command of the English language, which may decrease their likelihood of reading or telling stories to their children in English, compared with white parents.100,101

Additionally, cultural beliefs that teachers are the experts in these areas, coupled with limited parental education, may deter Latino parents from engaging their child in preliteracy activities.

Latino Kids Have Low Participation in ECE, Preschool

Participation in early care and education (ECE) and preschool programs is also suboptimal in Latino children and is a main contributor to poor school readiness.5,6 In recent years, several programs have been set forth to improve kindergarten readiness and create a trajectory of academic achievement, employment, and increased earnings for disadvantaged Latino children.

Participation in early care and education (ECE) and preschool programs is also suboptimal in Latino children and is a main contributor to poor school readiness.5,6 In recent years, several programs have been set forth to improve kindergarten readiness and create a trajectory of academic achievement, employment, and increased earnings for disadvantaged Latino children.

In the United States, almost 70% of 4-year-old children go to early learning centers.102

However, nearly six of every 10 4-year olds are not enrolled in publicly funded preschool programs, and even fewer are enrolled in the highest-quality programs.

Participation is particularly low for Latino children, at 40% compared to 53% of white children. Participation is also low for low-income children, at 41% compared to 61% of their more affluent peers.7

Lack of Availability Is a Big Reason for This Low Participation

In a study about the location of child centers across eight states, 42% of children younger than age 5 live in areas known as child care deserts, which either have no child care centers or so few centers that there are more than three times as many children as there are spaces in centers.103

The availability of child care centers is in a state of crisis for Latino families.

Several elements are critical for the ideal child care center:

- High-quality early childhood education centers should be more affordable and accessible to low-income Latinos, with higher density in Latino neighborhoods.104

- Early childhood education centers should offer services from birth through age 5 to allow single-site care of all children within one family, and continuity of cognitive assessments and interventions.104

- The location and design of early learning centers can support active transport and increased student physical activity throughout the school day.91

- Students who have access to nature at school engaged in physical activity 10 times longer than those students who had limited access to nature at school.105 Outdoor learning environments and green schoolyards, for example, can boost student’s academic performance, physical activity, mental health, and different types of play, which are critical for development.

- The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) states that unstructured free play is essential for children’s emotional development and can protect against stress, anxiety and depression in children.106

More information about families’ proximity to child care programs can inform local, state and federal efforts to increase access to early childhood programs, especially given the financial impact of early care and education programs.

Only 14% of public education dollars are spent on early childhood education.

Yet for every $1 spent expanding early learning, society receives a return on investment of $7 or more based on increased school and career achievement, as well as reduced costs in remedial education, health, social welfare programs, and criminal justice system expenditures.5,7,107,108

More from our The State of Latino Early Childhood Development: A Research Review »

- Introduction & Methods

- Key Research Finding: Latino Childhood Trauma

- Key Research Finding: Healthy Lifestyles

- Key Research Finding: Early Care and Education

- Key Research Finding: Strategy—Improve Early Care

- Key Research Finding: Strategy—Boost School Readiness

- Key Research Finding: Strategy—Reduce Childhood Trauma

- Key Research Finding: Strategy—Incorporate Family Values

- Key Research Finding: Strategy—Support Moms

- Policy Implications

- Future Research Needs

References for this section »

1. Guerrero, A. D. et al. Early Growth of Mexican–American Children: Lagging in Preliteracy Skills but not Social Development. Matern. Child Health J. 17, 1701–1711 (2013).

5. US Department of Education. A Matter of Equity: Preschool in America. (2015).

6. Yoshikawa, H. et al. Investing in our future: The evidence base on preschool education. (Society for Research in Child Development, 2013).

7. White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for Hispanics. Early Learning: Access to A High Quality Early Learning Program. Available at: https://sites.ed.gov/hispanic-initiative/files/2014/05/WHIEEH-Early-learning-Fact-Sheet-FINAL_050614.pdf. (Accessed: 25th October 2017)

96. Fuller, B. et al. Maternal Practices That Influence Hispanic Infants’ Health and Cognitive Growth. Pediatrics peds.2009-0496 (2010). doi:10.1542/peds.2009-0496

97. Ansari, A. & López, M. Preparing low-income Latino children for kindergarten and beyond: How children in Miami’s publicly-funded preschool programs fare. children 7, 9 (2015).

98. Ramirez, A. Building Support for Latino Families: A Research Review. Salud America (2017). Available at: https://salud-america.org/building-support-for-latino-families-research/. (Accessed: 25th October 2017)

99. Kenney, M. K. Child, Family, and Neighborhood Associations with Parent and Peer Interactive Play During Early Childhood. Matern. Child Health J. 16, 88–101 (2012).

100. Whaley, S. E., Jiang, L., Gomez, J. & Jenks, E. Literacy Promotion for Families Participating in the Women, Infants and Children Program. Pediatrics 127, 454–461 (2011).

101. Ryan, C. Language use in the United States: 2011. Am. Community Surv. Rep. 22, 1–16 (2013).

102. Bierman, K. L., Heinrichs, B. S., Welsh, J. A., Nix, R. L. & Gest, S. D. Enriching preschool classrooms and home visits with evidence-based programming: sustained benefits for low-income children. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 58, 129–137 (2017).

103. Malik, R., Hamm, K., Adamu, M. & Morrissey, T. Child Care Deserts – Center for American Progress.

104. Ramirez, A. Family Support Research: Policy Implications. Salud America (2017). Available at: https://salud-america.org/family-support-research-policy-implications/. (Accessed: 25th October 2017)

105. Tirabassi Sofield, B. M. It’s not child’s play: the impact of SES and urbanicity on access to recess. (Rutgers University-Graduate School of Education, 2013).

106. Council on School Health. The Crucial Role of Recess in School. PEDIATRICS 131, 183–188 (2013).

107. Karoly, L. A. The Economic Returns from Investing in Early Childhood Programs in the Granite State. (2017).

108. Heckman, J. J. Invest in early childhood development: Reduce deficits, strengthen the economy. Heckman Equ. 7, (2012).

By The Numbers

84

percent

of Latino parents support public funding for afterschool programs