Share On Social!

Recent data goes to proves alarming facts health experts and racial justice advocates warned of since the spread of COVID-19: Minority groups are experiencing the pandemic’s worst outcomes.

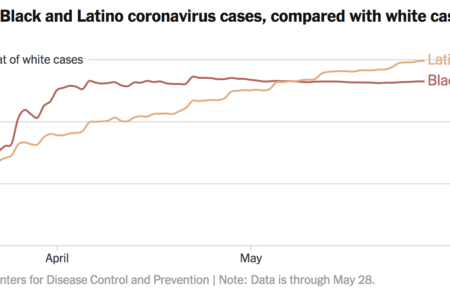

Latinos, Blacks, and other communities of color are three times more likely to contract coronavirus than white Americans, according to a new report from the New York Times—obtained through a lawsuit against the centers of disease control.

Worse, members of those groups are twice as likely to die.

“Systemic racism doesn’t just evidence itself in the criminal justice system,” Quinton Lucas, the third Black mayor of Kansas City, told the Times. “It’s something that we’re seeing taking lives in not just urban America, but rural America, and all types of parts where, frankly, people deserve an equal opportunity to live — to get health care, to get testing, to get tracing.”

The Report and its Findings

In Lucas’ home of Missouri, new data shows an alarming fact: 40% of infected induvial are Black or Latino.

These groups represent only 16% of the state’s population.

Worse, that example is one of numerous that illustrates the severity of racial inequities in healthcare. Across the board, whether it is the direct or indirect consequences of the pandemic, people of color are suffering the worst outcomes.

“Latino and African-American residents of the United States have been three times as likely to become infected as their white neighbors, according to the new data, which provides detailed characteristics of 640,000 infections detected in nearly 1,000 U.S. counties,” writers from the Times wrote in their report. “And Black and Latino people have been nearly twice as likely to die from the virus as white people, the data shows.”

While these numbers should be cause for alarm, they are not out of step with historic disparities minority groups. In fact, those systems of injustice play a part in why people of color are suffering such most significant threats, according to the CDC.

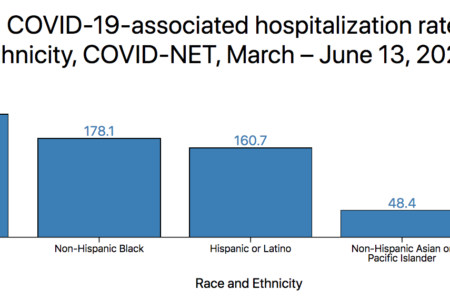

“Long-standing systemic health and social inequities have put some members of racial and ethnic minority groups at increased risk of getting COVID-19 or experiencing severe illness, regardless of age,” the CDC states. “Among some racial and ethnic minority groups, including non-Hispanic black persons, Hispanics and Latinos, and American Indians/Alaska Natives, evidence points to higher rates of hospitalization or death from COVID-19 than among non-Hispanic white persons.”

Coronavirus and Minority Groups

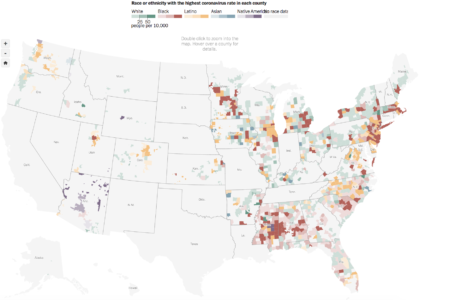

This is not an issue in certain parts of the country, either. Throughout the U.S., minority groups are suffering higher rates of infection and more significant fatalities from the disease.

Go here for the latest in coronavirus case and death rates among U.S. Latinos.

Unfortunately, this is nothing new.

People of color have dealt with injustice and inequity for too many years, according to Roberto Alcantar, the Chief Strategy Officer for the Chicano Federation.

“What this has done is put a light on the historical deficiencies and inequities that have plagued our community,” he told NBC 7, San Diego. “We don’t have the economic opportunity that we need. We don’t have access to the housing that we need or the education that we need. We have to look at affordable housing because one of the things that we’ve learned is that a lot of families have to share one rough because of a lack of access to affordable housing.

“And when you look at the fact that so many of our community members, particularly people of color and those in the South Bay, they make up so many of those essential workers.”

While these numbers are high, there is still action everyone can take to make a difference.

The Pandemic and What You Can Do to Help

In Massachusetts, nine out of the 10 highest COVID-19 infected cities are those with significant minority populations, according to Mass Live.

The state’s Public Health Commissioner Monica Bharel said these figures should serve as a critical example, among too many to count, of why racial issues must be addressed. You can help by getting your city or county to declare racism as a public health crisis.

“We have long understood that racism is a public health issue that demands action, and the disproportionate impacts of this new disease on communities of color and other priority populations is the latest indicator change is necessary,” she told Mass Live. “At the Department of Public Health, our mission is to eliminate health inequities, and we place equity at the core of all that we do.”

She is heading a task force, the COVID-19 Health Equity Advisory Group, that is addressing numerous issues concerning the pandemic — including racial disparities.

Not only is the group helping their state, but they are focused on providing resources for others. Some of their key recommendations include:

- Spread COVID-19 data among various groups and areas — focusing on those who are not receiving the needed information.

- Equally distributing personal protective equipment (PPE) among essential workers and professions most at risk.

- Focus on providing housing stability for those significantly impacted by COVID-19.

- Implementing greater outreach, especially multilingual approaches, to increase necessary action such as testing, safety precautions, etc.

- Require a diversity of representation in task forces and groups focused on managing the pandemic.

“Our approach to COVID-19 and future health challenges should be to strengthen the underlying health of the Commonwealth,” Thea James, an assistant professor at the Boston University School of Medicine and a member of the Advisory Group, told Mass Live. “We can do this by building resilient communities and taking a critical look at how systemic racism has influenced disinvestment in communities of color. These recommendations are a starting point for taking concrete next steps into action for a more equitable future.”

Stay up to date with health equity efforts in the aftermath of COVID-19

Editorial Note from New York Times: Data is through May 28 and includes only cases for which the race/ethnicity and home county of the infected person was known. Only groups that make up at least 1 percent of a county’s population are considered in determining the highlight color on the map. Sparsely populated areas in counties are not highlighted. The C.D.C. data included race/ethnicity information, but no county location, for infected people in eight additional states: Hawaii, Maryland, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Texas and Vermont.

Explore More:

Healthy Families & SchoolsBy The Numbers

142

Percent

Expected rise in Latino cancer cases in coming years