Share On Social!

For Maria Hernandez, fighting for health equity hits close to home.

When her dad was in the hospital fighting cancer, Hernandez had a realization.

“He’s being wheeled into the surgical unit, and he’s with me and my mom and my two brothers, and we’re all speaking Spanish, wishing him well. And all of a sudden, he puts up his hand and says, ‘Stop, don’t speak Spanish, they’re going to think I’m stupid, and they’re not going to help me.’ And that just took my breath away,” Hernandez said.

It made her realize that healthcare organizations must do more to address implicit bias.

“Here I was, working on diversity and inclusion issues in major corporations. And I thought, what is healthcare doing about this? And so I started looking into this,” Hernandez said.

Hernandez is the President and Chief Operating Officer for Impact4Health, an organization dedicated to reducing healthcare disparities through healthcare innovations, training, and effective community and stakeholder engagement.

Over the last decade, she has helped healthcare organizations address health equity through the Inclusion Scorecard for Population Health, a comprehensive checklist of 70 best practices that can help track inclusion, community engagement, and health equity.

Although she sometimes encounters people resistant to change or unaware of the importance of health equity, Hernandez is passionate to create a better environment in healthcare for everyone.

A Background in Academia

Hernandez started her career thinking she would be an academic but switched to consulting.

“I got trained as a community psychologist from the University of Texas at Austin. And I was in academia for the first six years of my career. But I started up as an entrepreneur created a consulting practice. And up until about 10 years ago, I primarily was focused in the corporate and foundation or major nonprofit sectors,” Hernandez said.

The experience with her father at the hospital led her to explore working with health equity.

“I started looking into this and I was really convinced that I needed to do more in healthcare than just working with companies that were making widgets and different things like that for consumers. So for the last 10 years, I’ve done a lot of different projects around access to care, the social determinants of health,” Hernandez said.

She was working with InclusionINC, a consulting firm that specializes in inclusion and diversity solutions, when she was encouraged to set up her own practice specific to health equity.

Four years ago, Hernandez started Impact4Health as a subsidiary of Inclusion Inc.

Around that same time, she got the idea for the Inclusion Scorecard after reading Atul Gawande’s book, The Checklist Manifesto, which details lists that surgeons should follow to ensure surgical processes were correct.

“I just thought, what an idea, why don’t we make a list of what it takes to create health equity? And that’s how the inclusion scorecard was really born. And now, you know, almost four years later, it’s the centerpiece of what we do, along with some training around unconscious bias prevention and culturally competent care,” Hernandez said.

Working to Promote Health Equity with the Inclusion Scorecard

Hernandez helped create the Inclusion Scorecard for Population Health along with InclusionINC, using her decade of experience in working with diversity and inclusion and the social determinants of health.

Hernandez created the scorecard, which launched 4 years ago thanks to the support of other health equity-focused organizations and a partnership with Insight Formation Inc. to support the technical development.

The scorecard is a customized online dashboard of best practices designed for healthcare leaders to address health care inequities as part of a comprehensive Population Health Management Strategy.

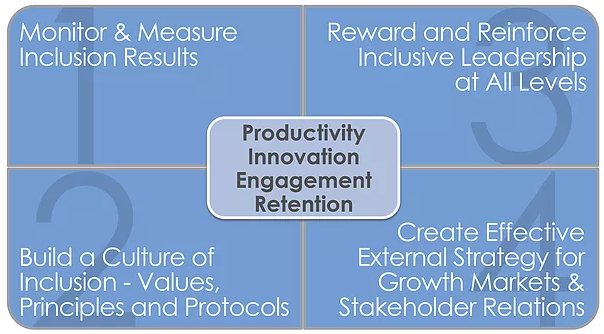

It is divided into four distinct quadrants:

- Tracking key metrics about the population served and the overall diversity of staff at all levels

- Building a culture of inclusion throughout the health system

- Creating greater accountability among leaders to address health disparities

- Developing higher engagement with diverse community stakeholders

Examples of some of the best practices from the quadrants include tracking patient health outcomes by demographic group, target health education and outreach programs tailored to vulnerable populations, reward and acknowledge effective inclusive leaders, and target outreach and health partnerships with community groups serving key populations.

Healthcare systems that partner with Impact4Health can access the online dashboard to measure how the metrics are being implemented. Most systems will custom choose the metrics that best fit their organization rather than use all 70 metrics.

Since the scorecard launched four years ago, Hernandez’s work centers around helping organizations implement the metrics.

“When the pandemic struck, we decided to offer that inclusion scorecard for free to any health system. And what that means is that they have access to about 70 different best practices that are organized into four different themes or focus areas. And it can be used to do a current state analysis of where that hospital system is and what are known best practices to advance health equity. So right now, we’re just swamped with a lot of work helping some of those organizations implement the scorecard,” Hernandez said.

Since the start of the pandemic and the resurgence of discussions about racism and racial disparities that occurred in 2020, Hernandez said more organizations want to talk about health equity.

“I think it’s fair to say that before the pandemic, it was super hard to talk about this, to get in the door even. And now I think that both the pandemic and the murder of George Floyd made it absolutely imperative that every system have some mechanism in place to advance health equity,” Hernandez said.

On a day to day basis, Hernandez meets with executives and helps them navigate what they can do to promote health equity.

“One of those things that people need to do is understand what challenges you have, what are the current conditions that you have to address, and then start training start developing those programs start implementing new policies and procedures that are going to meet the needs of those underserved communities,” Hernandez said.

Fighting Implicit Bias

Much of Hernandez’s work centers on educating people about implicit bias.

You can find out if you have implicit bias. Everyone has implicit bias, says Hernandez.

“We all make snap judgments. It’s human nature. Unfortunately, we’re wired to think about us versus them. It’s part of our survival mode. Once you are aware that you have unconscious bias, if you just ignore the impact of that, the way we make certain programs, the way we make certain policies, they are naturally human endeavors, and they’re going to be biased. That’s how structural racism works. That’s how implicit bias works,” Hernandez said.

Often, hospitals will have policies that exclude some groups due to bias, such as signage that excludes non-English speakers or restrictions on patient visitation.

“A lot of hospitals have visiting hours. At the system where I was a trustee, I think our visiting hours ended at 7 o’clock, and one of the trustees started to ask, ‘Who can make it anywhere in the Bay Area traffic by 7 o’clock?’ If you are privileged to have a manager role or an executive role, you can leave your job at any time, but if you’re an hourly worker, you can’t leave work early without some punitive factors. And so that one policy was a disadvantage for a group of patients and their families that was never intended,” Hernandez said.

Hernandez’s Inclusion Scorecard allows organizations to examine these kinds of policies and assess what they’re doing to avoid creating disparities in treatment.

“Our scorecard lists a lot of activities that an organization needs to look at in order to uncover where there are opportunities to reduce bias,” Hernandez said.

“Depending on your system, no one does all 70 at once, but you might choose those items that really resonate with the kind of system that you are, the population that you serve, and are you in an urban or rural environment. There’s a scoring mechanism and a knowledge base that each item is linked to, so that if the person conducting the assessment doesn’t know too much about that particular practice, they don’t have to start from scratch. We’ve given them some suggestions about how to do that.”

Patients can also play a role in making sure they advocate for themselves.

One way to do so is to bring an advocate with you to medical appointments.

“I think this is one thing that we need to talk about a lot in our community. And that is to understand, you have the right to bring someone with you to your appointments, you can bring your own advocate,” Hernandez said.

Challenges with Resistance to Change

Hernandez has faced some challenges as some people are uncomfortable talking about bias and racism. They may be resistant to changing their practices, she said.

“I think the challenge is that this is still a topic that’s really uncomfortable for a lot of people. Talking about unconscious bias, implicit bias, or systemic bias, racism, all of that continues to be very uncomfortable. And it’s made even more so because of the nature of the polarized dialogue that we have in our country,” Hernandez said.

Many healthcare organizations no longer have the capacity to address equity issues by themselves, which can be a challenge for Hernandez when figuring out how to implement necessary changes.

“I think that those who are really trying to make change happen are facing a lot of distraction in the healthcare system. A lot of people had to go to the front lines to just address the number of individuals coming in the front doors with COVID-19. And so some people that were working on diversity and inclusion issues were furloughed, or their staff was reduced because of the financial crisis that this created in some systems,” Hernandez said.

Another challenge for Hernandez is when healthcare organizations haven’t collected appropriate data from patients, such as race, ethnicity, and language preference (REaL) or sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI).

“We know that electronic health records are used to support the best possible continuity of care and making sure people are getting the information they need as they see different patients. What’s amazing is that, with all that data, people weren’t necessarily looking at factors based on REAL or SOGI demographics. Most boards just look at aggregated data, one number for patient satisfaction, or one figure for total number of rehospitalizations. And I started asking our board to begin to request that data be segmented by REAL and SOGI information,” Hernandez said.

Having that complete demographic information is essential for uncovering health disparities.

“Peter Drucker said ‘If it isn’t being measured, it’s not being managed.’ I got another one for you: if no one’s asking about it, and no one’s going to even look to think about managing it. So that’s a huge wake up call, I think that many systems are experiencing right now,” Hernandez said.

It’s important in situations where people don’t understand health equity to help them understand why it’s vital to address.

“I have encountered some pretty interesting dynamics in meetings where people kind of are dismissive. ‘Oh, this isn’t really that big of a problem,’ or the biggest sort of perspective among some physicians is, ‘Look, I treat everybody the same.’ Well, that’s a problem if you treat everybody the same, because that only works if everybody coming in your door is coming from the same circumstance. And we know that’s not the case,” Hernandez said.

How Hernandez Handles Equity Skeptics

When talking to people resistant to change, Hernandez makes sure to outline the facts.

“The most important argument to make about health equity is you can’t have quality of care unless you have health equity. If people who come through your doors have different experiences and different outcomes, just based on their language, or their sexual orientation, or their gender or ethnicity, something’s wrong. And you need to address that. And I know that people might dismiss that. But when you begin to look at the data, there’s pretty important information that can’t be ignored,” Hernandez said.

She points to statistics on racial disparities in health outcomes, such as Latino being more likely to have diabetes than their peers, which have been exacerbated by the pandemic.

“How do you explain that? There are lots of factors. But we’ve known about these inequities for decades. And I think once you start to present the data, I think it’s much less likely for people to dismiss it or ignore it,” Hernandez said.

Thankfully, the healthcare workforce is also diversifying more, which helps advocacy for patients of color.

“I think that the diversity of staff and the workforce changes that have occurred in the last 20 years have made for many systems to have internal advocates for this work. We’re seeing hospitals have employee resource groups for diverse employees. We’re seeing community advisory councils or patient advisory councils,” Hernandez said.

“They’re saying, ‘Let’s deal with this, let’s really tackle this’ because it’s clear we’ve not met some of the most basic things that we purport in healthcare – to treat everyone fairly, to treat everyone well, regardless of circumstance.”

Explore More:

Increasing RecognitionBy The Numbers

3

Big Excuses

people use to justify discriminatory behavior

This success story was produced by Salud America! with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The stories are intended for educational and informative purposes. References to specific policymakers, individuals, schools, policies, or companies have been included solely to advance these purposes and do not constitute an endorsement, sponsorship, or recommendation. Stories are based on and told by real community members and are the opinions and views of the individuals whose stories are told. Organization and activities described were not supported by Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and do not necessarily represent the views of Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.