Share On Social!

Amid the surging COVID-19 pandemic and one of the hottest summers in world history, public parks are a refuge.

But not all parks are created equitably.

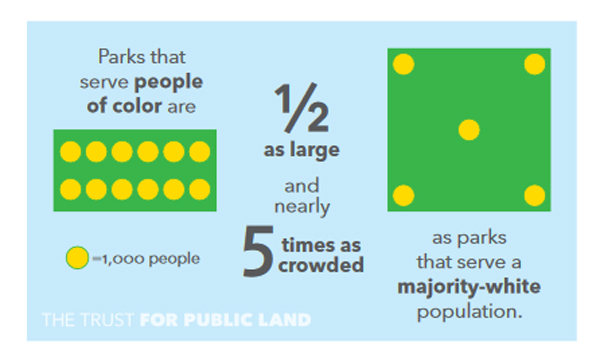

Parks that serve primarily Latinos and others of color are half the size of parks that serve majority White populations. They are also five times more crowded, with hotter temperatures, according to a new study from The Trust for Public Land.

“As cities struggle with extreme heat this summer, parks are one of the best ways for residents to find relief,” said Diane Regas, leader of The Trust for Public Land. “We all need and deserve parks—and all of the benefits they provide—all of the time. But during this period of compounded public health emergencies, unequal access to quality parks can be downright dangerous.”

What Did the New Study Examine about Park Access and Temperatures?

Parks are one of the few places Americans can safely escape home isolation.

In parks, people can remain socially distant while walking, bicycling, and getting fresh air. Parks—especially those that are densely wooded and deep green—also can counter urban temperatures exacerbated by heat-trapping buildings, pavement, and concrete, according to The Trust for Public Land.

The agency analyzed park land in 14,000 U.S. cities.

The Trust for Public Land researchers overlaid satellite heat data with census tract data, converted that thermal data from satellite imagery into a heat value, and applied heat values to every 30-by-30-meter geographic area (excluding large conservation areas and national forests), NPR reports.

They made two main findings.

1. Communities with Nearby Parks Are Cooler than Those with No Nearby Parks

The Trust for Public Land found that areas within a 10-minute walk of a park are as much as 6 degrees cooler than areas beyond that range.

Leafy, green parks are especially cool. Research increasingly recognizes the power of trees and plants to provide shade and cool the air.

Leafy, green parks are especially cool. Research increasingly recognizes the power of trees and plants to provide shade and cool the air.

This cooling effect happens inside parks, and also beyond their borders. It even extends into surrounding neighborhoods a half-mile away, according to the The Trust for Public Land study.

“Greenery and trees bring down the overall temperature of an area, and at night they serve to cool the neighborhood rather than trap the heat,” said Surili Patel, director of the American Public Health Association’s Center for Climate, Health and Equity. “Parks will offer some reprieve for those who don’t have air-conditioning.”

2. Not Everyone Has Equitable Access to Parks that Lower Temperatures and Allow Safe Social Distancing

Parks serving primarily people of color are half the size of parks that serve majority white populations. They are also five times more crowded.

Many of these parks are not and green. Rather, they have more concrete and asphalt.

Many of these parks are not and green. Rather, they have more concrete and asphalt.

“Black, Indigenous, Latinx, Asian, Pacific Islander, and multiracial populations—when they do have parks within a 10 minute walk—are likely to find small, crowded spaces, not the kind of parks that allow for easy social distancing or ample cooling shade,” according to The Trust for Public Land analysis.

In addition, parks serving primarily low-in-come households are, on average, four times smaller—25 acres versus 101 acres—than parks that serve a majority of high-income households.

What Does This Study Mean for Latinos and Equitable Parks?

Latino neighborhoods face some of the most dire park shortages.

Distance is a top barrier to Latino access to parks and other green spaces.

Only 1 in 3 Latinos live within walking distance (<1 mile) of a park. Park-less Latinos miss out on space for physical activity, social interaction, and stress reduction.

Only 1 in 3 Latinos live within walking distance (<1 mile) of a park. Park-less Latinos miss out on space for physical activity, social interaction, and stress reduction.

Other barriers are safety, a lack of street, sidewalk, and transit connectivity, as well as a lack of programming and funding issues, according to a research review by Salud America! at UT Health San Antonio.

“Green space can provide a sense of community and feelings of safety by creating vital neighborhood hubs for social interaction,” according to the review. “For residents of inner-city apartment buildings, urban green spaces have been linked to stronger ties with neighbors and a greater sense of safety.”

What Can We Do to Address Equitable Access to Parks, Green Space?

Latino kids who interact with nature early in life have cognitive changes, which improve behavioral development.

Boosting access can start with new parks.

In a Latino-majority part of Chula Vista, Calif., promotoras worked with the community to push for the area’s first park in more than several decades.

“People are always using the park,” said local advocate Margarita Holguin.

It also entails sharing what is already available, but perhaps locked up.

Shared use agreements, for example, are formal contracts between entities that outline the terms and conditions for sharing facilities—such as school yards—with the public and surrounding neighborhoods. Read how one California town got both a new park and implemented a shared use agreement.

Green space initiatives are effective when they meet Latino community needs.

Needs include using a community park as a hub for neighborhood events, social services, and connections to healthcare, repurposing vacant lots into play spaces, and creating greenways as safe routes to school, public transit, according to a research review by Salud America! at UT Health San Antonio.

“By incorporating these characteristics into green space initiatives that impact communities with a large number of Latino residents, policymakers can maximize green space use and improve the physical and psychological well-being of Latinos in their communities,” according to the review.

Let’s Address Systemic Racism, Even in Our Park Systems!

Park development, like many other environmental and economic systems, are linked to historical racism.

“We need to look at how parklands came to be,” said Jose Gonzalez, founder of Latino Outdoors. “That’s very true in terms of our national parks system and state parks. But even looking at cities, it’s how they were designed, who they were designed for, and what the historical reasoning was for that. It’s not surprising, when you look at parks and even tree cover, how that aligns with other metrics of socio-economic status.”

And, as we know, racism is a public health crisis.

So what can you do?

Download the free Salud America! “Get Your City to Declare Racism a Public Health Crisis Action Pack“!

The Action Pack will help you gain feedback from local social justice groups and advocates of color. It will also help start a conversation with city leaders for a resolution to declare racism a public health crisis. This can include a commitment to take action to change policies and practices.

The Action Pack will help you gain feedback from local social justice groups and advocates of color. It will also help start a conversation with city leaders for a resolution to declare racism a public health crisis. This can include a commitment to take action to change policies and practices.

Dr. Amelie G. Ramirez, director of Salud America! at UT Health San Antonio, created this Action Pack with input from several San Antonio-area social justice advocates.

Explore More:

Green & Active SpacesBy The Numbers

33

percent

of Latinos live within walking distance (<1 mile) of a park