Share On Social!

Pedestrian fatalities have increased 50% since 2009.

Autonomous vehicles—those driven by automated driving systems rather than a human—are often suggested as a solution by politicians, planners, even some safety advocates.

But with our nation’s struggle to regulate the automobile industry and failure to protect people walking, many worry about the decades-long shift to autonomous vehicles because cars will still dominate roads and road design.

Moreover, many worry that electric driverless vehicles district from the social, economic, and health issues cities are facing today.

“Public health will benefit if proper policies and regulatory frameworks are implemented before the complete introduction of [autonomous vehicles] into the market,” according to David Rojas-Rueda of Colorado State University and his colleagues in Texas, Washington, and Spain.

The Wrought History of U.S. Vehicle Safety Regulations

In the first five decades of motordom, the automobile industry argued that driver education was the key safety rather than standardized safety features and devices.

They pushed back against seatbelts, shatterproof windshields, collapsible steering wheels, and air bags.

Finally, in 1966, Congress required automakers to include seat belts in every car they built.

However, many states didn’t require drivers to use seat belts.

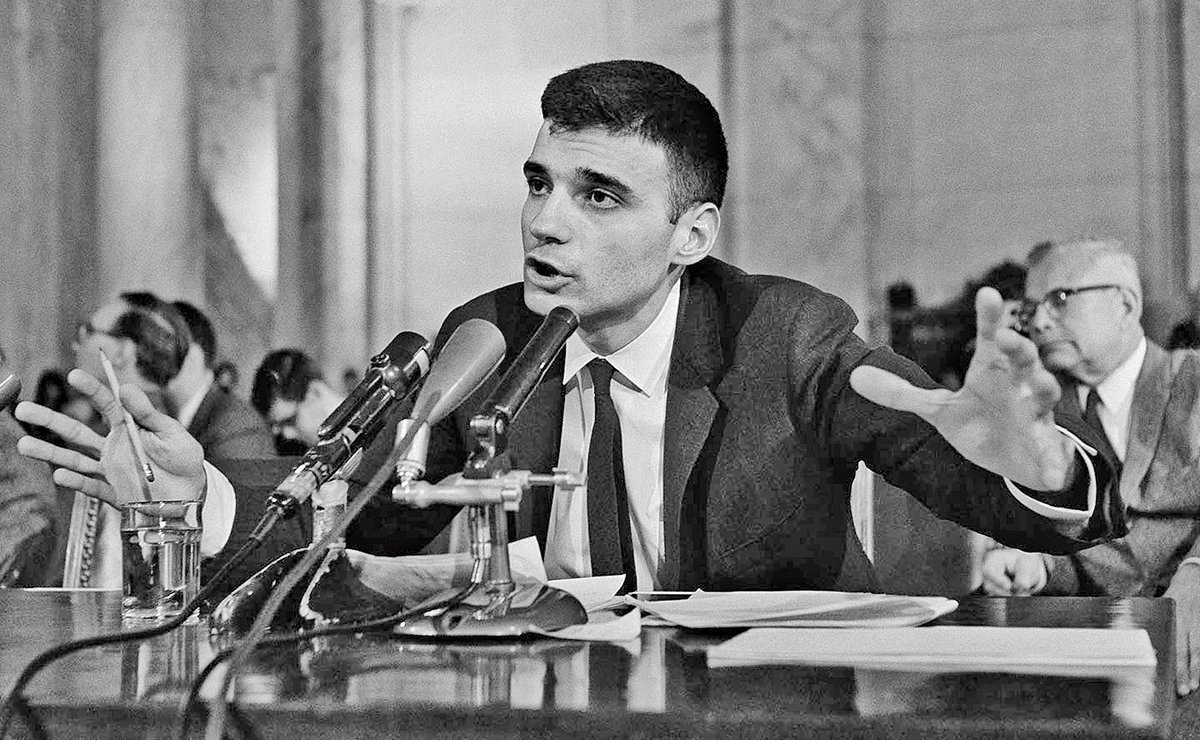

Thus, safety and consumer advocates, like Ralph Nader, urged the federal government to mandate passive restraints, like air bags. Nader’s 1965 book, “Unsafe at Any Speed: The Designed-In Dangers of the American Automobile,” prompted the 1966 Motor Vehicle Safety Act and, a few years later, the creation of the federal safety agency that became the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

“For over half a century the automobile has brought death, injury and the most inestimable sorrow and deprivation to millions of people,” Nader’s book begins.

For the next decade, Nader and other advocates pushed legislators and automakers to adopt safer devices without much success.

“Ralph Nader charged [on Sept. 12, 1977] that auto makers were showing “callous indifference to human life on the highway” by opposing air bags or automatic seat belts cars,” according to a 1977 article in the New York Times.

They continued advocating for yet another decade, but government officials continued siding with the auto industry.

“President Reagan, who has sought to ease regulatory burdens on industry, has opposed federally required passive restraints on the ground that the costs outweigh the benefits,” according to a 1984 article in the New York Times.

It wasn’t until 1991 that Congress passed a law requiring automakers to include driver and passenger front airbags in all new passenger vehicles. However, it wouldn’t go into effect until 1999.

It took another decade for half of vehicles on the road to be equipped with air bags.

This means for 40 years people continued to be unnecessarily killed and seriously injured on American roads.

Given that there was a 45% spike in people walking killed by people driving from 2010 to 2019, we cannot tolerate decade-long delays in safety regulations.

Slow Fleet Turnover

Today, the average age of vehicles on the road is 12.1 years. This is the highest it has been since age started being tracked in 2002. Roughly 25% of vehicles are older than age 16.

That’s why it takes years for new technologies, like airbags, to become mainstream on our roads.

This is known as slow fleet turnover.

This is known as slow fleet turnover.

We have seen it with electric vehicles, and we will see it with autonomous vehicles.

Though electric vehicles hit the market in 2010, only roughly 1% of vehicles on the road today are electric, according to the New York Times.

Even if the auto industry makes the drastic shift to electric vehicles to the point where they make up one-quarter of new sales in 2035, only 13% of vehicles on the road would be electric.

With electric vehicles, slow fleet turnover is beneficial because it gives states time to prepare for the increased demand for electricity.

“If millions of Californians with electric cars came home in the evening and immediately started charging all at once, it would put a major strain on the grid — and this in a state that has recently been suffering from blackouts,” according to Brad Plumer with the New York Times.

Vehicle Occupants Prioritized Over People Walking

In the decades since Nader’s book, much of the investment in automobile safety features has only benefited occupants inside the vehicle.

While seatbelts, shatterproof windshields, collapsible steering wheels, and air bags are important, they do nothing to protect everyone else on the road.

Moreover, American cities are failing at traffic safety.

Street design continues to focus on moving more cars faster.

“American road engineers tend to assume people will speed, and so design roads to accommodate speeding; this, in turn, facilitates more speeding, which soon enough makes higher speed limits feel reasonable,” writes Peter C. Baker in The Guardian.

Worse, the auto industry continues to design larger vehicles with more power and faster speeds.

“As with speeding, there appears to be a self-perpetuating cycle at work: the increased presence of large cars on the road makes them feel more dangerous, which makes owning a large car yourself feel more comforting, Baker writes.”

Crashes and higher speeds and crashes with larger vehicles are more forceful, thus more deadly.

Pedestrians are two to three times more likely to die when hit by an SUV or pickup than by a passenger car.

The Tragic Results of a Lack of Focus on People Walking

Between 2009 and 2016, SUVs had the biggest spike in single-vehicle fatal pedestrian crashes, jumping 81% over the eight-year period, according to the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety.

At the same time, the U.S. experienced the largest percentage increase in pedestrian fatalities among 30 countries in the Organization for Economic Co-operation & Development, 24 of which experienced decreases in pedestrian fatalities, according to the International Transport Forum’s Road Safety Annual Report 2019.

“A conventional car is likely to strike a pedestrian in the legs, propelling them over the hood of the vehicle,” according to Justin Tyndall, assistant professor of economics at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, in Economics of Transportation. “A vehicle with a higher front end is likely to make first contact with the pedestrian’s torso or head, harming vital organs and deflecting their body under the vehicle.”

Because of the rising size of vehicles on U.S. roads, Tyndall wanted to explore the impact of vehicle size on road deaths.

He found that larger vehicles are related to more pedestrian fatalities.

“Pickup trucks, minivans and SUVs all significantly increase pedestrian fatalities relative to cars,” according to Tyndall.

Tyndall also found no evidence that the shift toward larger vehicles improved aggregate safety.

And still, pedestrians are not the only ones at higher risk of death due to larger vehicles.

“The drivers of smaller cars are 158% more likely to killed by pick-up truck drivers in the event of a collision, and 28% more likely if they’re struck by someone behind the wheel of an SUV,” according to Kea Wilson with Streetsblog USA.

Unfortunately, there are disparities in who is getting killed.

“Because women, low-income people, and people of color are all less likely to buy big cars, they’re also disproportionately more likely to be killed by the driver of one, whether they’re on foot or driving themselves,” according to Wilson.

Yet, the government does not regulate the size or weight of these vehicles.

Regulating Breakaway Poles

Another example of a safety feature that only benefits vehicle occupants is breakaway poles.

At the base of breakaway poles—highway signs, traffic signals, and streetlights—is a series of bolts that attach the pole to its base buried in the ground.

At the base of breakaway poles—highway signs, traffic signals, and streetlights—is a series of bolts that attach the pole to its base buried in the ground.

These bolts are designed to break when hit by a vehicle to protect people inside.

“This is done because cars leave the street surface with such frequency, and with such violent force, that many drivers were being injured and killed hitting poles that did not yield,” according to Strong Towns founder and president Charles Marohn.

Keep in mind that people walking and biking stand next to these poles every day.

Rather than design streets to slow drivers and increase safety for everyone, time and money were again invested to only protect those inside the out-of-control vehicle.

“Ponder this the next time you are standing at the signal, waiting to cross,” Marohn said. “The next time you are standing in space that licensed professionals have recognized is so dangerous that the extra effort and expense to absorb that violent force is justified to protect those in vehicles.”

Meanwhile, the government fails to regulate vehicle size.

“For the past 50 years, a singular focus on consumer protection has persistently prevented auto-safety regulators from addressing serious external hazards created by dangerous automobile designs,” according to researcher John Saylor in his forthcoming paper in the University of Pennsylvania Law Review.

These concerns have increased in recent years as automakers develop and test new technology, such as automated driving systems, on our roads.

Concerns spiked in June 2021 when the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSD) sent a letter calling the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) to better regulate automated vehicles.

NTSB Calls on NHTSA to Better Regulate Automated Driving Systems’ Safety

As of March, NHTSA had 27 investigations open into crashes of Tesla-brand automated vehicles, according to David Shepardson with Reuters.

In April, two people were killed in a Tesla when the automated vehicle crashed into a tree and caught fire.

“Authorities told [TV station] KPRC that it took four hours, 32,000 gallons of water and a call to Tesla to extinguish the flames because the vehicle batteries kept reigniting,” according to Jonathan Ponciano with Forbes.

Due to a lack of federal safety standards to regulate automated vehicles, states have established their own regulations. This has caused a patchwork of requirements that fails to protect Americans. You can track autonomous vehicle bills in your state here.

NTSD also investigates automated vehicle crashes.

“In the Tempe crash investigation, we determined that Arizona’s lack of a safety-focused application-approval process for [automated driving systems] testing at the time of the crash, and its inaction in developing such a process after the crash, demonstrated the state’s shortcomings in improving the safety of [automated driving systems] testing and safeguarding the public,” NTSB Chairman Robert L. Sumwalt, III wrote in a letter to NHTSA.

Sumwalt of NTSB sent the letter in response to the patchwork of state regulations, recent crashes with autonomous vehicles, and the Department of Transportation’s voluntary safety initiative.

In June 2020, the Department of Transportation (DOT) launched a voluntary Automated Vehicle Transparency and Engagement for Safe Testing (AV TEST) initiative.

“The goal of the initiative is to provide the public with direct and easy access to information about testing of [automated driving systems]-equipped vehicles, information from states regarding activity, legislation, regulations, local involvement in automation on our roadways, and information provided by companies developing and testing [automated driving systems],” according to NHTSA.

At the time, 80 companies were testing autonomous vehicles on public roads, but only 20 had submitted voluntary safety assessments.

However, since the system is voluntary, DOT cannot ensure the quality of the information that is shared.

Sumwalt’s letter calls on NHTSA to better regulate automated driving systems’ safety:

“The NTSB recommend that NHTSA require the submission of safety self-assessment reports and establish an ongoing process for evaluating them, determining whether appropriate safeguards—such as adequate monitoring of vehicle operator engagement, if applicable—are included for testing a development [automated driving system] on public roads.”

During the public comment period on proposed changes to the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD), for which 2,100 people visited our Salud America! model comments, many professionals, cities, and organizations called out inadequate guidance regarding autonomous vehicles.

For example the Central Texas Families for Safe Streets included the following model comment from the National Association of City Transportation Official (NACTO):

“Remove the Manual’s new proposed chapter on Autonomous Vehicles. The Manual’s new chapter on Autonomous Vehicles (Part 5) places these road users at the top of a new modal hierarchy by absolving AV companies of the responsibility to build vehicles that keep all road users safe within the existing transportation network. Upgrading street markings to be compliant with the proposed MUTCD could cost taxpayers billions of dollars; and if the markings are non-compliant and an AV-involved crash occurs, taxpayers will likely foot the bill for that as well.”

The Self-Driving Coalition for Safety Streets included recommendations to improve the chapter on autonomous vehicles in their comment.

But they stated “AVs do not require separate or unique infrastructure that is different from what human drivers use, and establishing a separate section for AVs may lead to the mistaken impression that infrastructure improvements are necessary to deploy AVs at scale.”

Even if government officials were able to adequately regulate automated driving systems to protect both occupants and non-occupants, slow fleet turnover means we are decades away from promised safety benefits.

Can Driverless Vehicles Deliver on Their Safety Promises?

It isn’t clear how many fatalities and serious injuries can be prevented by automated driving systems.

Although driver error is thought to be responsible for nine in 10 crashes, analysis from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety “suggests that only about a third of those crashes were the result of mistakes that automated vehicles would be expected to avoid.”

The Institute reviewed more than 5,000 police report crashes and separated driver-related factors that contribute to crashes into five categories:

- Sensing and perceiving

- Predicting

- Planning and deciding

- Execution and performance

- Incapacitation

They found that errors linked to planning and deciding, like speeding and illegal maneuvers, were contributing factors in about 40% of crashes.

“The fact that deliberate decisions made by drivers can lead to crashes indicates that rider preferences might sometimes conflict with the safety priorities of autonomous vehicles,” according to the Institute.

After all, the driverless vehicles being tested on our roads now still require a human driver to share the driving efforts. There is not yet a true self-driving car.

“We don’t yet even know if this will be possible to achieve, and nor how long it will take to get there,” according to Lance Eliot with Forbes. Read more about his top four Congressional issues when it comes to true self-driving cars. The True Need Now: Design Safer Streets

Beyond regulating automobiles, pedestrian safety can also be improved by taking a systemic approach to changing roadway design.

After all, traffic fatalities are not random. They often occur on specific types of roadways.

Researchers recently studied roadway characteristics where fatal pedestrian crashes are concentrated. These “hot spot” corridors are a 1,000-meter-long section of roadway where six or more fatal pedestrian crashes occurred during an eight-year period.

They found that 97% of hot spot corridors were roadways with three or more lanes, and 77% had speed limits of 30 mph or higher.

Safety concerns are so widespread in America that engineers, planners, and advocates submitted 25,000 public comments calling for safety reforms to the 700-page Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD), one of transportation engineering’s “bibles” that guides road creation.

One particular problem with these dangerous corridors is they are also not random. They are often found in low-income, largely Latino or Black neighborhoods.

The researchers found that 88% of the most dangerous roadways for pedestrians are located in low-income neighborhoods. 53% are located in majority-minority neighborhoods.

“Ultimately, the engineering and planning professions must prioritize pedestrian safety over automobile mobility in order to save lives,” according to the study. Vehicle Emissions Regulations

Although automobile regulation has led to more electric and fuel-efficient vehicles in America over the past few decades, we have not seen a decline in emissions.

This is because people are driving more.

“Between 1990 and 2019, GHG emissions in the transportation sector increased more in absolute terms than any other sector (i.e. electricity generation, industry, agriculture, residential, commercial), due in large part to increased demand for travel,” according to a fact sheet on emissions from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

The recently proposed vehicle emission standards and fuel economy standards are not enough to offset increased vehicle travel.

Similarly, President Biden’s executive order, which set a non-binding target of making 50% of all new passenger vehicle sales zero-emission vehicles in 2030, is also not likely enough to offset increased vehicle travel because these vehicles will account for only roughly 3% of all vehicles on the road.

Zero-emission vehicles include battery electric, plug-in hybrid electric, and fuel cell electric vehicles; however, it is a misleading name for this group of vehicles because emissions are generated during manufacturing.

This demonstrates a shortcoming in how we measure and talk about the environmental impacts of motordom.

While transportation is the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in America, generating roughly 2,000,000,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide annually, this number does not provide an authentic measure of emissions associated with vehicles because it only accounts for end-use emissions or tailpipe emissions from consumption.

The transportation sector accounts for 29% of greenhouse gas emissions in the US while electricity production accounts for 25% and industry accounts for 23%.

Emissions measured in the transportation sector are only from consumption, thus only from the combustion of fuel during operation regardless of the emissions generated in manufacturing and powering these vehicles.

Even if there is a reduction in tailpipe emissions in the transportation sector due to reduced dependence on combustion engines, electric and autonomous vehicles will continue to generate emissions in the electricity production and industry sectors. Because manufacturing a new vehicle is so resource- and energy-intensive, we should reduce our overall dependence on vehicles rather than merely shift the fuel source of those vehicles.

Also, because, as mentioned previously, electric driverless vehicles will increase demand for electricity production, we should reduce our overall dependence on vehicles.

Moreover, because vehicle travel generates non-tailpipe emissions, like particulate matter from brake, tire, and road wear regardless of the fuel source, we should reduce our overall dependence on vehicles.

Electric Driverless Vehicles Distract from Other Problems

Beyond traffic fatalities and tailpipe emissions, cities are facing numerous social, environmental, and health issues related to motordom. These include transportation-cost burden, opportunity hoarding, obesity, urban heat island, and poor air quality.

Doctors and healthcare workers are so worried about the negative impacts of inadequate and unsafe transportation options that they proposed new codes related to transportation insecurity to CDC National Center for Health Statistics’ International Classification of Diseases-Clinical Modification, Tenth Revision (ICD-10-CM).

“When 100% of residents in your county are transportation-cost burdened, meaning they spend more than 15% of their annual income on transportation, they have less expendable income for health food, child care, and preventative health care, which negatively impacts health across the lifespan,” said Dr. Amelie G. Ramirez, director of Salud America! at UT Health San Antonio.

Communities can’t thrive when residents’ economic security is threatened because inaccessible, inadequate, unaffordable, unreliable, and unsafe transportation options is a barrier to getting and keeping a job.

Electric driverless vehicles cannot solve these problems.

While we need better regulation of autonomous driving systems to ensure the safety of all people on the road regardless of whether they are inside a vehicle, we can neither wait for nor rely on the development and introduction of this safety technology.

We need solutions to traffic fatalities and injuries now. We need solutions to the social, economic, and health impacts of transportation cost-burden now.

Due to slow vehicle turnover and the fact that most vehicles on the road for the next few decades will continue to be operated by humans, conversations about autonomous vehicles must go beyond traffic safety and conversations about electric vehicles must go beyond tailpipe emissions. Regardless of what fuels the vehicle or who drives the vehicle, we need to reduce size, speed, and miles traveled.

“Ultimately, because cities are trying to solve numerous social, environmental and health issues, we need to prioritize safe streets for people walking and biking and increase investment in frequent transit,” Ramirez said.

Explore More:

Transportation & MobilityBy The Numbers

142

Percent

Expected rise in Latino cancer cases in coming years