Share On Social!

Every person is a unique individual.

But if you look closely, you’ll see each person lives, learns, works, and plays within social and environmental conditions that influence their individual health and wealth.

Some people face health barriers because of structural and systemic policies that curb their access to quality housing, transportation, medical care, food, jobs, schools, parks and other social determinants.

Individuals have no choice when it comes to these structural health barriers.

“Despite the tremendous, lifelong impact of our community conditions on our health, we focus most of our energy and resources on treating the outcomes of these problems but lack the essential urgency for attacking the root causes of poor health,” according to Brian C. Castrucci, Dr. Johnathan Fielding, and John Auerbach.

That is why we encourage our network to take action to reduce systemic inequities, and shift from individualist thinking to structuralist for health equity.

Individualist vs. Structuralist Views of People Living in Poverty

In the United States, many have a negative view of those living in poverty.

Beliefs about the causes of poverty fall into three types, according to a Salud America! Research Review:

- individualist, where poor people themselves are believed responsible due to immorality, poor money management, or laziness;

- structuralist, where the socioeconomic system itself fails to provide jobs, sufficient wages, and good schools; and

- fatalist, where poverty is believed to be a result of illness, handicaps, or bad luck.

The individualist view is most common.

People with the individualist view may feel like they are exempt from feeling compassion for or taking action against systemic inequities that lead to poverty, because they assume current social, economic, and political systems are fair and advantageous, otherwise they would not be in place.

A person’s poverty must be due to lack of hard work or a lack of ambition, individualistic thinkers believe.

But poverty and poor health are neither situational nor random. They are structural.

We must avoid buying into the individualist mentality because it shuts the door on opportunities to address structural and systemic inequities that continue to unfairly burden some Americans.

At the population level, it is more efficient to remove structural barriers to health and wealth than to focus on individual efforts to overcome the barriers.

This is why it’s important to help people shift from the individualist narrative and toward the idea of creating a community that achieves health equity, where everyone has an opportunity to stay healthy and thrive regardless of their income, race, or gender.

Here are four reasons to help you build a case against individualist thinking and support structuralist thinking.

1. Reason for Structural Inequity: Poor Health

Latino and low-income families face worse health outcomes because they are disproportionately burdened by substandard schools, poor housing, unsafe streets, costly transportation, unequal pay, nutrient-poor food and adverse childhood experiences.

These burdens are not random, unique, or situational.

Rather, these burdens are common, structural, and rooted in discriminatory practices and policies.

Blaming a person’s poor health on their individual behavior without addressing these underlying burdens, is like a doctor who treats a symptom without addressing the underlying cause. Why else would places like Chicago and San Antonio have a 19-year gap in life expectancy between neighborhoods based on race/ethnicity and poverty?

Racial inequities will continue to grow unless we consciously work to eliminate them.

To make long-lasting changes in promoting health equity for our nation, we need to move beyond individualist thinking and toward structural thinking that addresses systemic inequities in the social and environmental conditions in which live, learn, work and play.

We need meaningful action and a shared narrative shift toward supporting equitable systems and structures that tackle the following three structural inequities:

2. Reason for Structural Inequity: Lack of Affordable Housing

Housing plays a critical role in health.

However, housing problems aren’t random.

Lack of stable, affordable housing is a common problem, particularly in areas with large Latino populations. This common problem is the result of decades of discriminatory policies and systemic inequities.

Single-Family Zoning. Zoning is a land use regulation that divides and regulates how land can be used.

On most land zoned for residential use, as opposed to commercial or industrial, zoning prohibits everything but a single-family detached house.

This means no duplexes, triplexes, or quadplexes. It often also means no small lots or small homes.

By prohibiting various affordable housing types, single-family zoning excludes people with low-incomes.

This means people with low-incomes are systematically denied access to wealthier neighborhoods, thus also denied access to opportunities within wealthier neighborhoods, such as parks and quality schools.

In tandem with this exclusionary zoning practice was decades of disinvestment in black and brown neighborhoods, to include a racist practice called redlining.

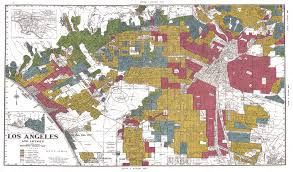

Redlining. Beginning in the 1930s, the federal government relied on maps made by the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) to determine who was eligible for a federal housing loan.

The problem is these maps graded neighborhood risk by race. Black and brown neighborhoods were defined as “definitely declining” or “hazardous” and graded as “high-risk,” while white neighborhoods were defined as “still desirable” or “best” and graded as “low risk.”

Similar to single-family zoning, which excludes people by class, redlining excluded people by race.

For decades, government officials, loan officers, appraisers, and real estate professionals literally determined lending risk by drawing a red line around minority neighborhoods. They did this in 239 U.S. cities. Find your city here.

Not only were minority neighborhoods left out of federal investment in homeownership, but these neighborhoods were also left out of state and local investment in various other opportunities and amenities, like schools and parks.

These communities are still not invested in equitably today, and Latinos and other minorities continue to be routinely denied mortgage loans at rates far higher than their white counterparts.

Even programs aiming to address housing affordability problems fall short. For example, the methods used to determine fair market rent levels for housing voucher subsidies are determined at the county or multi-county level, which ignores variety among neighborhoods and sets the voucher subsidy too low.

This means even with a voucher, low-income families are priced out of high-opportunity neighborhoods.

The white advantage and racial disadvantage we see today is not random. It is systemic.

For example, according to a 2018 report from the National Community Reinvestment Coalition:

- 91% of white neighborhoods classified as “best” remain middle-to-upper-income today

- 86% of white neighborhoods classified as “best” remain predominantly white today

- 74% of minority neighborhoods classified as “hazardous” remain low-to-moderate income today

- 64% of minority neighborhoods classified as “hazardous” remain predominately minority today

Beyond living in disadvantaged neighborhoods, people of color also are housing-cost burdened.

Housing-Cost Burden. Nationwide, a higher percentage of Latinos (56.9%) than whites (46.8%) are housing cost burdened, according to a Salud America! Research Review.

These families have less expendable income for transportation, healthy food, child care, preventative health care, higher education, professional development, and more.

Housing affordability and stability affect financial stability, stress, and the overall ability of families to make healthy decisions. Rising housing costs also leads to involuntary displacement of families from urban areas to non-affluent suburbs and rural spaces, known as the suburbanization of poverty. These families are further away from jobs, transit, parks, healthy food, health care and social networks.

Renters are particularly vulnerable to rising housing costs, substandard conditions, and eviction all while missing out on the opportunity to build wealth.

The affordable housing problem is neither unique nor random, but is common and structural; thus, cannot be solved by ambition or exceptional money management.

Focusing on individuals’ needs is not an effective way to solve a structural problem.

Learn more about housing conditions in your county by downloading our free Health Equity Report Card.

3. Reason for Structural Inequity: Inadequate Transportation Options

Transportation plays a critical role in a person’s health and wealth.

It can connect families to employment opportunities, affordable housing, healthy food, quality child care, vocational training, social support, medical care, and other important destinations.

Yet, for Latinos, lack of safe, affordable, and reliable transportation options is a common problem.

This is the result of systemic discriminatory policies and structural inequities that built a transportation network where you must own a private vehicle in order to get around. These practices were in large part to reinforce the classist and racist housing practices mentioned above by investing in roadways to connect white suburbs to city centers while disinvesting in transit.

Disinvestment in Options. Vehicle ownership is expensive. Yet many communities are designed for vehicle access and lack safe sidewalks and frequent public transit.

Many think this is because fuel taxes pay for highways.

However, highway spending has exceeded revenue from federal and state gas taxes.

Every year since 2008, a gap has formed between dedicated gas tax revenues flowing into the Highway Trust Fund and the cost of surface transportation spending Congress has authorized, according to a 2020 report from the Congressional Research Service.

Every year since 2008, a gap has formed between dedicated gas tax revenues flowing into the Highway Trust Fund and the cost of surface transportation spending Congress has authorized, according to a 2020 report from the Congressional Research Service.

Over the past 12 years, Congress has transferred nearly $144 billion from the general fund to the Highway Trust Fund.

At the local level, gas taxes are rare, meaning, general fund appropriations provide the largest share of local highway revenue, according to a 2014 report from The PEW Charitable Trusts.

However, despite revenue coming from general funds, spending on highways exceeds that for transit at each level of government.

For a trip that takes 20 minutes by car, some people report leaving up to two hours early to be sure they arrived to work on time due to inadequate transit.

Unsafe Streets. Our transportation network kills more than twice as many people per capita as the following high-income countries: New Zealand, Canada, France, Japan Germany Spain, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and Sweden.

On streets in America, Latinos, people of color, low-income populations, and older populations are killed or seriously injured while walking at higher rates.

Again, this illustrates that the problem is structural, not individual.

Not only are auto-dependent transportation networks unsafe, but they are also connected to higher rates of physical inactivity, greenhouse gas emissions, land degradation, and economic segregation.

Not only are auto-dependent transportation networks unsafe, but they are also connected to higher rates of physical inactivity, greenhouse gas emissions, land degradation, and economic segregation.

Transportation-Cost Burden. To be considered affordable, families should spend no more than 15% of their income on housing and transportation.

However, numerous households are paying more than 22% of the annual income on transportation in counties across the country.

For example:

- 62% of households in Miami-Dade County, Florida (69.1% Latino) spend more than 22% of their annual income on transportation

- 72% in Maricopa County, Arizona (31.4% Latino)

- 75% in Bexar County, Texas (60.7% Latino)

- 68% in Tulare County, California (65.2% Latino)

The average annual household expenditure on transportation was $10,742, with only roughly $4,300 for purchasing the vehicle, and the rest on fuel, insurance, and maintenance, according to Consumer Expenditures in 2019 by the U.S. Department of Labor’s U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Without options, families are forced to own a private vehicle just to get to work. They must forego buying necessities like food and healthcare to cover the cost of car ownership and repairs.

This is a structural problem.

Focusing on individuals’ transportation needs is not an effective way to solve this structural problem.

We need safe, reliable transportation options.

You can find out more about transportation issues in your county by downloading our free Health Equity Report Card and by looking up the H+T Index.

4. Reason for Structural Inequity: Racial/Gender Pay Gap

The racial/gender pay gap negatively impacts economic stability.

However, unequal pay among Latinas and Latinos is a common problem.

On average, white households have nearly seven times the wealth of black households and five times the wealth of Latino household.

Median Latino household wealth decreased 50% in a recent 40-year span (1983 to 2013), while that of white households increased by 14%, according to a Salud America! Research Review.

This is due in part to racist practices that blocked minority families from homeownership as well as to unfair wages.

Historically, wages for women and minorities have been unfairly established. Employer practices, such as using prior salary history in setting current pay, compounds the problem.

However, many wage discrimination laws do not address using salary history in setting pay for new hires.

Hard work and college haven’t been the answer to racial pay gaps.

For example, college didn’t help close the black-white or Latino-white wage gap. In fact, Latinos with a college degree earned roughly the same proportion of white wages in 2018 (82%) as they did in 2000 (83%), and black people with a college degree earned a smaller proportion of white wages in 2018 (79%) than they did in 2000 (83%).

Latinas who have bachelor’s degrees, for example, are paid 35% less than white men with the same degree.

Despite college, hard work, and ambition, racial and gender pay gaps remain a structural issue.

Promoting Structuralist Thinking

To address inequities that affect health, it is important to make the distinction between individual-level interventions to address social needs, and structural-level interventions to address systemic inequities.

Although individual-level efforts to address social needs can be less expensive, these efforts will only achieve short-term, individual gains. This is because they don’t address the root causes of the systemic inequities that cause poor health.

For example, helping people get over a barrier is not as effective as eliminating that barrier, particularly when we are talking about structural barriers that have been in place for decades.

Improving health equity depends on improving structural conditions and decreasing social vulnerability to prevent the emergence of unmet social needs.

Share this with policymakers, health system leaders, and other stakeholders urging them to focus on structuralist efforts to reduce systemic inequities.

One way to help our cities start to shift more rapidly to structuralist action is to help them declare racism a public health crisis (and commit to concrete action).

You can help your city do this.

Download the free Salud America! “Get Your City to Declare Racism a Public Health Crisis Action Pack“!

The Action Pack will help you gain feedback from local social justice groups and advocates of color. It will also help you start a conversation with city leaders for a resolution to declare racism a public health issue along with a commitment to take action to change policies and practices. It will also help build local support.

By The Numbers

23.7

percent

of Latino children are living in poverty