Share On Social!

As an avid cyclist, Brian Pearson loved riding the new $8 million hike-and-bike trail in his town of Fall River, Mass. (8% Latino).

Then he learned a new road project could damage the trail.

The 2.4-mile Alfred J. Lima Quequechan River Rail Trail—which fully opened in May 2017 after nine years of work and an $8 million investment by the state to improve mobility and access to safe places to play—was jeopardized when city officials tried to enable a developer to build a road that would have crossed and re-routed the trail.

Pearson and others were outraged.

They gathered information, attended city meetings, and held a rally. They even hired a lawyer to fight for trail preservation.

Would it be enough to save the trail?

Restoring the River

Source: Green Futures FB

The Quequechan River Rail Trail was born out of an abandoned railroad line during a time when environmental organizations were discussing ways to restore the Quequechan River after 150 years of pollution and neglect.

Founded in 1803, the City of Fall River is named after the Quequechan River, which means “falling water” in Wampanoag for the series of six cascading falls over a 130 foot drop.

Fed by the Watuppa Ponds, the Quequechan River and ponds were overtaken in the 1800s by numerous textile and granite mills using the river for power, cooling, and waste.

Fall River was a thriving city in 1875 when the railroad was built next to the Quequechan River. It was the largest textile producing city in the country.

However, in 1910, concerns about pollution from mills and manufacturers as well as from lack of sewers was brought to light.

“The chief sources of pollution of the stream are the manufacturing establishments which have no sewer connection, and from which sewage and mill wastes find their way into the river,” the report states, according to a 1914 report from the Watuppa Ponds and Quequechan River Commission to the Massachusetts Association of Boards of Health.

Many Fall River residents were and remain unaware of these issues as the river flowed beneath the streets and buildings.

“There was very little awareness back then about the importance of wetlands,” Alfred Lima, former city planner and Green Futures research director, and trail namesake, said to the Herald News in 2009.

“An examination of the river when the water is shut off at the Watuppa Dam, and the lower river bed is exposed, shows that for a considerable part of its length the stream is filled, often to a depth of several feet, with the accumulated silt, sewage and other filth of many years. The depth of the sludge at many places, to say nothing of the odors arising when it is uncovered, make it impossible for a human being to traverse the length of this portion of the river,” the report states.

“To anyone who visits the river at periods of low water, it is strikingly apparent that the sanitary condition of this stream is one which should not be tolerated in the heart of any city,” the report states.

Eventually, the mills and railroads were abandoned, and highways became the new scourge.

When Interstate 95 was built in the 1950s, it split the city in half, blocked access to the river, and diverted the falls underground through a series of culverts

This was another reason environmental organizations, like Green Futures, were advocating for river restoration.

The city named for its falling river no longer had its falls, and its river was dirty.

In 1987, the Conservation Law Foundation filed suit against the City of Fall River to control its combined wastewater and stormwater system discharges; in 1989, United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued an Administrative Order requiring the City to abate its combined sewer overflow discharges and bring the system into compliance with the federal Clean Water Act; and in 1992, a federal court order was issued mandating the Fall River Combined Sewer Overflow Abatement Program, according to the City of Fall River Integrated Wastewater and Stormwater Master Plan.

As the began the comprehensive planning process to resolve numerous, environmental organizations used it as an opportunity to advocate for river restoration, a greenway trail and opportunities to repurpose the old mills.

“This is not some utopian idea — it’s been done in other places successfully,” Lima said to the Herald News. “The river and the falls are the heart and soul of the city; it’s the right thing to do.”

Lima helped create a vision plan for the Quequechan River, with a bike path along the abandoned railroad.

“I had done a bike plan for the City of Fall River, and this was a natural growth of that,” Lima said.

In Fall River, the railroad line was within 1-mile radius from half the city’s residents, more than one-third of which don’t own a vehicle.

The Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT) wanted to repurpose abandoned railroad lines like this, and local and state groups wanted to restore the river and provide more walking and biking routes.

Brian Pearson, the Chairmen of Bike Fall River, said he recalls playing pick-up football in street as a child but didn’t dare ride those streets today with his wife.

“It’s very difficult to ride in Fall River,” Pearson said.

Pearson said they left town to find trails to ride.

Turning the rail into a trail could greatly benefit residents’ mobility and access to nature, which is of utmost importance in a city that has worse obesity, diabetes, and physical activity rates than the state overall.

MassDOT, recognizing this in 2008, built the first 0.6-mile section of the Quequechan River Rail Trail in Fall River to boost walking and biking.

“This trail goes through heart of the city and it can bring people from their neighborhood to city places,” Pearson said.

But the country fell into a recession. This and other rails-to-trails projects stalled.

Trail Re-Started and Finished

A resurrection didn’t occur until 2011.

Several groups, led by the Southeastern Regional Planning and Economic Development District (SRPEDD), began discussing plans for a 50-mile regional bike network across southeastern Massachusetts, including Fall River.

Watch the 2012 Fall River Bicycle Committee PSA narrated by Pearson.

So the Metropolitan Area Planning Council and MassDOT’s Mass in Motion campaign did a health impact assessment in 2012 to explore a second phase the Quequechan River Rail Trail.

Source: Screenshot from Nightfire Quequechan River Rail Trail Fly Through

The assessment made recommendations for engineering, design, and maintenance of a full 2.4-mile trail with trail lights, visible signage, and improving overall city and regional connectivity.

MassDOT, Mass in Motion, SRPEDD, the City of Fall River, local bike groups, and many others, like Pearson, got involved in public meetings about the design of the proposed trail.

MassDOT agreed to pay to acquire land for the project and build the trail through the Commonwealth’s 2008 Environmental Bond Bill. All property purchased for open space and recreational use from this source would be permanently conserved for that purpose under Article 97 of the Massachusetts Constitution.

The second phase of the Quequechan River Rail Trail began in 2015.

Another trail section opened in June 2016. A final section opened in May 2017.

The trail was a win, connecting the previously bisected city under I-95.

Pearson said he sees people using it to walk, bike, roller-blade, get fresh air, and walk to the store and other businesses.

“The river was the life blood of the city for the mills, and now, it is the life blood for people to get out in nature,” Pearson said.

About 62% of trail users reported walking more since the trail opened, and 15% of users said they used the trail for functional purposes, such as grocery shopping or getting to and from work, according to a 2016 survey.

“Now the people of Fall River have discovered this beauty that’s in the middle of the urban setting,” Pearson said. “I’ve had people tell me, ‘It doesn’t feel like I’m in the city anymore,’ even though you’re only a few hundred feet from the highway and away from busy streets.”

Trail in Jeopardy

At the September 2017 Bike Fall River Committee meeting, someone mentioned plans for a private road across the trail.

“Nobody is going to do that, that’d be foolish,” Pearson and other committee members thought.

Then, trail users spotted surveyors flagging the trail.

“That’s when all hell broke loose,” Pearson said.

Pearson, a previous city council member, called city staff immediately.

He found that Fall River Mayor Jasiel Correia sent an easement order to the City Council for Clover Leaf Developers in February 2017.

An easement is a legal right to a limited use of another’s property, such as running sewer or water under ground or a driveway across.

In this case, the rail-trail is the city’s property.

This easement was poorly written, failed to mention a roadway and the rail trail, and failed to include the planning documents, Pearson said. At 11 p.m., the City Council unanimously approved the easement order.

The easement would enable a two-lane road that would not only cross over and squeeze against the newly constructed rail trail but also reconfigure it, creating two 90-degree angles on the path that are dangerous for bikers and walkers.

Source: WSAR screenshot

“The intent of the trail was to take people away from traffic and away from cars, and by allowing a road to cross it, it would create a safety hazard,” Pearson said. “Some people won’t want their children there because it will be hazardous.”

Cycling enthusiasts expressed disappointment in the city’s lack of transparency.

City Council members said the easement order didn’t mention a road that would affect the trail, only water or sewer that would go underneath the trail. The mayor said he thought the Council would seek clarification if confused, according to news reports.

“Democracy was basically undermined by this whole thing,” Lima told a Herald News staffer.

“The state gave us an $8 million gift of the Alfred J. Lima Quequechan River Trail, a bike and pedestrian linear park, and this is how the city shows its gratitude,” said Julieann Kelly, Mass in Motion coordinator, according to the Herald News.

Nearly 75 people, including Pearson and Lima, showed up to a city meeting in September 2017 to request that the mayor and city council stop plans to build the new road. Pearson and others also urge city officials to address all future discussions in a public forum.

The mayor said he would suspend road plans.

“Like everything else in the city of Fall River, everyone needs to stay vigilant, super, super vigilant,” Joseph Carvalho, a rail trail advocate and retired history teacher, told the Herald News.

Trail Still Under Threat

Source: Fall River Bike Committee FB

Pearson and others worried the mayor didn’t immediately nullify the easement order.

“If the developer goes to court, they will win because the city gave them a legal easement,” Pearson said.

Pearson wanted to find out more, so he contacted many city departments, MassDOT, the Attorney General, a state senator, and he filed a freedom of information act through both the city and the state.

“We requested emails, agreements, studies, everything possible so we could look at who was to blame,” Pearson said.

His efforts uncovered some interesting documents from years earlier.

The state, the city and environmental organizations had already said no, Pearson said.

In October 2013, on separate occasions, the Secretary of the Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs (EEA), and the engineering firm Fay, Spofford, & Throndike (FST) said the roadway was not feasible. FST cited the 5,000 square feet of wetlands that would be permanently impacted and that crossing the path is considered hazardous to trail users.

“It would wipe out wetlands to move the rail trail and put in a two-lane private road,” Pearson said.

In December 2013, the EEA and the City of Fall River sent a joint letter to Clover Leaf Mills in response to their letter requesting driveway access over and reconfiguring of the rail trail. They gave numerous reasons why they were against the easement and proposed trail rerouting:

- MassDOT cannot expend state or federal funds to signalize a private driveway.

- Property interested purchased for open space and recreational use from [the Commonwealth’s 2008 Environmental Bond Bill] must be permanently conserved for that purpose under the terms of Article 97 of the Massachusetts Constitution.

- A revised design routing the trail to the north onto private property would require the construction of boardwalk trail in a wetland area and would have other detrimental impacts on wetland resources.

- Simply put, adding a road crossing, even with a relatively low traffic volume diminished the experience of the [trail] user.

Pearson doesn’t understand how the mayor could send an ambiguous easement letter to city council in 2017, when multiple agencies had said the private road was not feasible.

Pearson also found documents where the state and the city had agreed to protect the trail.

Prior to construction of the rail trail, the city and the state entered into an agreement to protect, preserve and enhance all open spaces under Article 97 of Articles of Amendment to the Massachusetts Constitution. Agencies shall not sell, transfer, lease, relinquish, release, alienate, or change the control or use to this land.

Simply put, it would be a violation of Article 97 if the city allowed the road.

However, neither the state nor the city followed through to protect the trail.

In fact, it appeared that someone in the city intentionally used city funds for a portion of the trail project in attempts to make it ineligible for Article 97, Pearson said.

“Somebody had to make a decision to circumvent the law by using city funds even though we have the original letter to the treasurer directing the city to use state bond funds,” Pearson said.

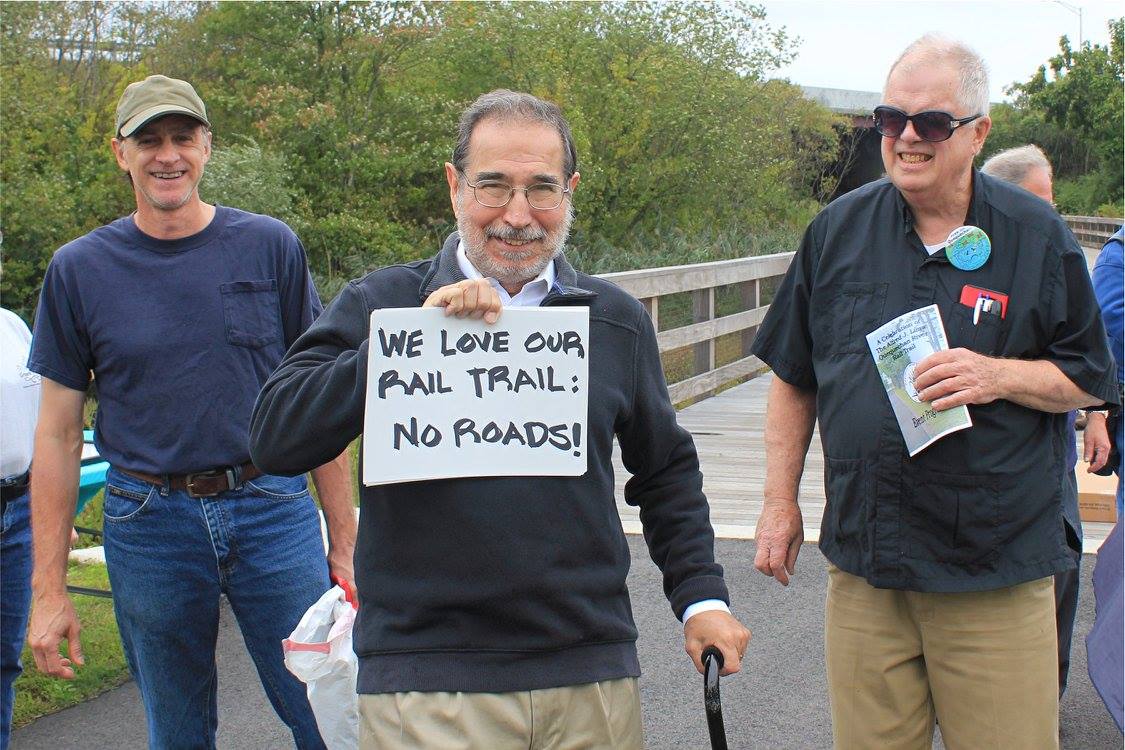

In October 2017, the Friends of the Quequechan River Rail Trail held a rally and bike ride to raise awareness about this issue and share this information.

Pearson and others spoke passionately at this event about saving the trail and asked attendees to show up at the next City Council meeting for support.

In November 2017, the City Council petitioned the court to reverse the easement.

The mayor vetoed it.

Hiring a Lawyer to Help Save the Trail

In late November 2017, Pearson, Green Futures, Friends of the Quequechan River Rail Trail, two neighborhood associations, and other trail advocates started the Alliance to Save the Trail.

Their first order of business was to raise funds to hire a lawyer.

If the Attorney General wasn’t going to rule that the city disobeyed Article 97 and nullify the easement, the residents will take legal action, Pearson said.

“A bunch of citizens putting their hard-earned money towards an attorney to try to force the government to do their job,” Pearson said.

The lawyer produced a letter stating that this trail should be protected under Article 97 because the city used state funds for design, engineering, appraisals, paperwork and an attorney.

Source: Fall River Bike Committee Facebook

Pearson and others set up a meeting with the state attorney general to deliver the letter, explain the situation, and ask to protect the trail.

“It’s so important to preserve because of the neighborhood it serves, low-income neighborhoods under the I-95 corridor,” Pearson said.

They are waiting to hear back, as of July 2018.

“We know we’ve proved our point. Our problem now is we are fighting the government to enforce their law,” Pearson said. “We are still raising awareness, holding rallies, and sharing about the beautiful trail on social media.”

Stay connected on the latest rail trail developments with the Fall River Bike Committee on Facebook!

Rail trail advocates were even nominated for the Herald News Newsmaker of the Year.

In July 2018, the Urban Land Institute (ULI) nominated the Alfred J. Lima Quequechan River Rail Trail, along with four other finalists, for their Open Space Award. The winner will be announced at the 2018 ULI Fall Meeting in October 2018.

If you don’t live in Fall River, join a walking or biking group in your city. Speak up to elected leaders and urge them to protect safe places to walk and bike for mobility and health!

By The Numbers

1

Supermarket

for every Latino neighborhood, compared to 3 for every non-Latino neighborhood

This success story was produced by Salud America! with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The stories are intended for educational and informative purposes. References to specific policymakers, individuals, schools, policies, or companies have been included solely to advance these purposes and do not constitute an endorsement, sponsorship, or recommendation. Stories are based on and told by real community members and are the opinions and views of the individuals whose stories are told. Organization and activities described were not supported by Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and do not necessarily represent the views of Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.