Share On Social!

Some big changes in 2022 and 2023 have set up the healthcare sector to advance screening for non-medical social needs in 2024 and beyond.

This is great news as we work to address social determinants of health (SDoH), improve health outcomes, and reduce health disparities.

But one key social need – transportation – isn’t getting the attention it deserves.

Transportation is a foundational social need and often co-occurs with other needs and/or acts as a barrier to resolving other needs.

Yet transportation is often poorly conceptualized, thus is poorly operationalized in social need screening tools and related justifications.

In this post, we review the following big changes as they relate to transportation as a SDOH:

- Big Change 1: In 2022, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) passed its final rule on Special Needs Plan (SNP).

- Big Change 2: In 2022, CMS passed its final rule on the Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR) Program.

- Big Change 3: In 2022, the Joint Commission published social need screening accreditation requirements.

- Big Change 4: In 2023, CMS’ Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation released their five-year evaluation report of the Accountable Health Communities (AHC) Model, which screened Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries for five core health-related social needs and provided navigation to community services.

Before we explore these changes, let’s define transportation as a social need.

Transportation is a Foundational Health-Related Social Need

Individual health is influenced by a variety of non-medical factors, like where people are born, grow, live, learn, work, play, and age.

These conditions are known as Social Determinants of Health (SDoH).

The primary pathway through which SDoH harm health and contribute to inequities in health is through adverse living conditions, which are known as social risk factors.

Social risk factors, such as dirty, dangerous, or inadequate transportation, for example, can directly impact health through exposure to toxins, traffic violence, or barriers to medical care. They can also indirectly impact health by causing health-related social needs, such as lack of access to education, employment, food, and other essential services and resources or financial hardship that hinders spending on food, medication, and other essentials.

Because of these direct impacts, transportation is a key social need.

And because of these indirect impacts, transportation is a foundational social need.

Why Is Transportation a Foundational Health-Related Social Need?

Several studies show that transportation is a foundational social need.

Two peer-reviewed studies in 2022, which assessed the relationship between multiple health-related social needs and health outcomes, found that transportation had the strongest relationship with health outcomes despite that transportation was the fifth-least prevalent social need in both studies.

Another study, which assessed the link between social needs and hospital stays among Medicare beneficiaries, similarly identified transportation as the fifth-least prevalent among seven social needs.

However, transportation “had the largest association with increased hospital stays and ED visits.”

The study also found that of the seven social needs, only “unreliable transportation and financial strain were associated with increased rates of 30-day readmissions.”

Similarly, another study, which assessed the relationship between social needs and health outcomes among a predominantly Latino population at a federally qualified health center, found transportation as the fifth-least prevalent among nine social needs.

Yet transportation was “the only social need associated with increased odds of chronic illness severity, diabetes, and psychiatric illness.”

Despite that transportation needs were not as prevalent as other health-related social needs throughout these studies, it is clear transportation needs played an outsized role in worse health outcomes.

Additionally, given the high prevalence of concurrent social needs found in both studies, transportation needs are also thought to play an outsized role regarding other health-related social needs.

“Transportation may be considered a more foundational need in relation to other more immediate needs, such as food or affording utility bills,” according to the authors of the latter study.

This idea that transportation plays an outsized role regarding other social needs was acknowledged in the five-year evaluation report of the Accountable Health Communities (AHC) Model.

Unexpectedly, the evaluation found that social need screening and community resource navigation did not markedly increase connections to community services, did not resolve health-related social needs, and did not markedly improve health care costs, service utilization, or health outcomes.

The report explains that lack of transportation was one of the four key challenges that participants faced in using community services, which could contribute to the unexpected findings.

In other words, not only is transportation a core health-related social need that impacts hospital stays and health outcomes, but transportation is also a barrier to resolving other health-related social needs.

Despite Being Foundational, Transportation is an Understudied Social Need

The problem is that there is no standardized method for assessing transportation needs and barriers.

Thus, multiple approaches and measurement instruments exist to assess transportation needs and barriers across screening tools, research studies, and intervention evaluations.

For example, in a 2014 synthesis of peer-reviewed studies on transportation barriers to healthcare access, most of the 61 studies used a different instrument to measure transportation barriers.

Similarly, in a 2022 content analysis of 23 social need screening tools, only 12 tools included one question specific to transportation needs. Only two tools included more than one question specific to transportation needs.

Most of the 14 social need screening tools used a different question to measure transportation needs.

“It is clear there is not yet a single standard measure for either screening or for comprehensively assessing transportation needs and resources,” the authors stated.

These studies demonstrate the lack of consensus on measuring transportation needs and barriers.

Additionally, most studies, screening tools, and interventions focus on medical transportation rather than non-medical transportation.

This means we know little about the indirect impacts on health, such as transportation barriers that hinder access to education, employment, food, and other essential services and resources or transportation cost burden that hinders spending on food, medication, and other essentials.

The lack of methods to understand non-medical transportation is problematic because, as mentioned above, transportation barriers co-occur with and hinder the resolution of other social needs.

While a standardized measurement instrument cannot guarantee accurate, consistent, and comparable data, the absence of a standardized measurement instrument threatens the analysis and interpretation of these data.

Given the growing emphasis nationwide on screening for and addressing health-related social need in health care, we need valid and reliable measurement instruments to assess transportation needs and barriers.

Following are four examples of the growing emphasis on screening for and addressing health-related social needs and summaries about how transportation is considered as a social need.

Big Change 1: The 2022 Medicare Advantage and Part D Final Rule: Social Need Screening Through Special Needs Plans (SNP)

In 2022, CMS issued a final rule that requires Medicare Advantage Special Needs Plans (SNPs) to include social needs questions in the initial and annual health risk assessment of each SNP beneficiary.

The rule took effect in January 2023.

SNPs were established in 2003 through the Medicare Modernization Act as a new type of Medicare Advantage coordinated care plan focused on special needs individuals.

“SNPs are either [Health Maintenance Organizations (HMO)] or [Preferred Provider Organizations (PPO)] plan types, and cover the same Medicare Part A and Part B benefits that all Medicare Advantage Plans cover,” as well as extra “benefits and services to people with specific diseases, certain health care needs, or who also have Medicaid,” according to CMS.

Health risk assessments were established in 2010 through the Affordable Care Act, which authorized an annual wellness visit for Medicare beneficiaries and required the provision of a health risk assessment as required as part of that annual wellness visit.

Health risk assessments were established in 2010 through the Affordable Care Act, which authorized an annual wellness visit for Medicare beneficiaries and required the provision of a health risk assessment as required as part of that annual wellness visit.

The new Medicare Advantage and Part D Final Rule requires that all Medicare Advantage (MA) SNP health risk assessments (HRAs) must include at least one question on each of three health-related social need domains: housing stability, food security, and access to transportation, according to CMS Transmittal 130, which communicates new/changed policies and procedures that will be incorporated into the CMS Online Manual System.

To the issue of which questions about housing stability, food security, and transportation can be included in the health risk assessment, CMS specified that the wording of individual questions would be established through sub-regulatory guidance for which they provided examples of specific questions and explained their criteria for selecting screening instruments.

According to the final rule, SNPs can either use a state-required screening instrument or a validated, health information technology-encoded screening instrument to select which questions from each of the three domains to include in the health risk assessment. These instruments can be found in the National Library of Medicine Value Set Authority Center (VSAC).

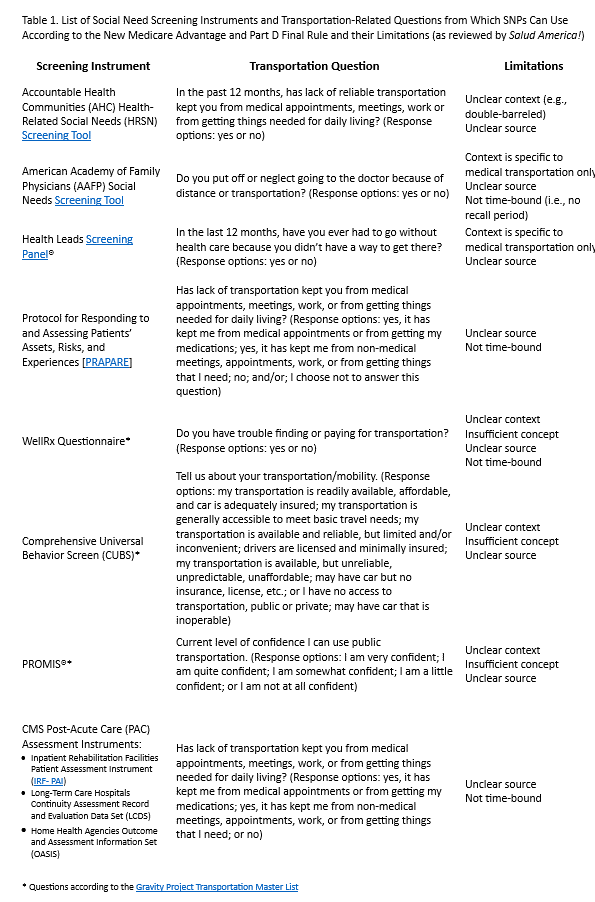

In Table 1, see the list of eligible screening instruments for transportation-specific questions that SNPs can use in the health risk assessment.

We want to point out that CMS defines transportation needs as “unmet transportation needs include limitations that impede transportation to destinations required for all aspects of daily living,” and because “all aspects of daily living” encompasses non-medical transportation, we think screening questions could also ask about non-medical transportation beyond medical transportation.

Thus, we performed a preliminary review of these eligible transportation questions to determine if they capture these distinct contexts (i.e., medical vs non-medical transportation).

Our preliminary review is in terms of concepts, contexts, and sources.

Concepts are the different aspects of how people experience transportation needs/barriers, such as time costs vs. monetary costs, a major obstacle vs. a minor inconvenience, or a necessity vs. a preference. Because transportation needs/barriers is an abstract concept, adequate conceptualization is necessary to identify and capture information about the most relevant aspects of this concept.

Contexts are the situations in which people experience transportation needs/barriers, such as accessing medical care, food, employment, or other opportunities. Because both medical and non-medical transportation impact health outcomes, it is important to capture information about both as distinct contexts.

Sources are the causes of or why people experience the transportation needs/barriers, such as insufficient transit, burdensome vehicle costs, or no vehicle. It is important to understand the sources of transportation needs/barriers to inform interventions, investments, and policy changes that address the root causes of transportation needs/barriers to prevent them from arising in the first place.

“These solutions must include upstream interventions that address root causes of disparities in SDOH, including economic and environmental factors, and mitigate their inequitable health impacts,” according to first-ever White House U.S. Playbook to Address Social Determinants of Health.

We identified the limitations of the eligible SDoH screening questions in these terms and included them in Table 1.

We identified the limitations of the eligible SDoH screening questions in these terms and included them in Table 1.

Overall, the purpose of this CMS requirement to include one question on each of the three health-related social need domains in SNPs health risk assessments is to improve health outcomes.

“This requirement helps to better identify the risk factors that may inhibit enrollees from accessing care and achieving optimal health outcomes and independence and enable SNPs to take these risk factors into account in enrollee individualized care plans,” according to CMS Transmittal 130.

However, the measurement instruments eligible to fulfill this new requirement are insufficient to identify transportation as a foundational health-related social need.

Big Change 2: 2022 Final Rule on Social Need Screening Through Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR) Program

In August 2022, CMS released a final rule requiring that hospitals screen for and report on patients experiencing health-related social needs, if the hospital participates in a pay-for-reporting quality program.

The rule proposed voluntary reporting in 2023 and mandatory reporting in 2024.

The final rule is regarding the Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS), which updates Medicare fee-for-service payment rates and policies and applies to general acute care hospitals paid under IPPS.

“CMS sets base payment rates prospectively for inpatient stays based on the patient’s diagnoses and any services performed,” and pays acute care hospitals and long-term care hospitals under the IPPS.

As the largest payer of health care services in the U.S., CMS is required by law to update these payment rates every year.

However, it is not as simple as a flat payment.

CMS manages quality programs to encourage hospitals to improve the quality of health care through payment incentives and payment reductions.

A key aspect of this is through program requirements.

For example, participating hospitals must meet certain requirements to receive the full payment for the inpatient services they provide to Medicare patients.

One program in the IPPS is the Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR) Program, and it is a pay-for-reporting quality program, which means that hospitals that do not meet all the Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR) requirements will receive reduced payments.

Not only is there an incentive to meet the requirements, particularly quality reporting requirements, but there is a disincentive for failing to meet them.

A new requirement in CMS’ IPPS Final Rule, which went into effect January 2024, is that hospitals participating in the Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR) Program must do the following:

- screen patients for five health-related social needs;

- report how many patients they screened for health-related social need; and

- report how many patients were identified as having one or more health-related social need.

Of note, similar to the Joint Commission (to be covered later), they use the term health-related social need (HRSN) rather than SDoH because they are only screening for individual-level social need rather than community-level social risk factors that contribute to those needs. Also of note, they use the term social drivers of health rather than social determinants of health.

The result of this new requirement is that hospitals that do not meet these social need screening and reporting requirements will receive a reduced payment for the inpatient services they provide.

Ultimately, this means that CMS is using social need screening as a requirement for hospitals in the Inpatient Quality Reporting to receive the full payment for the services they provide.

However, it is important to note that this requirement is about ensuring screening, not ensuring standardized screening.

Unlike the Medicare Advantage and Part D Final Rule explained in the previous section, where CMS requires SNPs to pull questions from one of seven approved social need screening instruments, which we identify limitations of in Table 1, the CMS’ IPPS Final Rule does not require the use of any specific screening instruments.

In other words, CMS does not require that inpatient hospitals participating in the quality reporting program use a standardized screening tool to report health-related social needs.

While CMS recommends the use of the 10-item Accountable Health Communities (AHC) Health-Related Social Needs Screening Tool and “suggest hospitals refer to the Social Interventions Research and Evaluation Network (SIREN) website, for example, for comprehensive information about the most widely used HRSN screening tools,” they state that “providers could use a self-selected screening tool and collect these data in multiple ways, which can vary to accommodate the population they serve and their individual needs,” according to the final rule.

Some public comments on the proposed rule discouraged such flexibility and recommended use of a standardized screening tool to support data comparison across hospitals and interoperability of these data.

In response to these comments, CMS stated, “we anticipate additional emphasis on standardized and validated screening instruments in future versions of this measure,” according to the final rule.

They also stated, “we encourage hospitals to use certified health IT that can also support capture and exchange of drivers of health information in a structured and interoperable fashion so that these data can be shared across the care continuum to support coordinated care.”

See Table 1 for the transportation-specific question from the AHC Health-Related Social Needs Screening Tool that CMS recommends for this new requirement.

As listed under limitations, this question is double-barreled and, because it does not offer distinct response options, the context in which people experience transportation needs/barriers is unclear.

This question does not capture needs/barriers in the context of non-medical transportation as distinct from those in the context of medical transportation. Rather, it combines medical and non-medical transportation.

Also listed under limitations, this question does not capture the source of transportation needs/barriers, thus is unable to inform either individual-level or community-level strategies.

In its IPPS Final Rule, CMS explained that through the following mechanisms, identifying health-related social needs has the potential to address the disproportionate health care expenditures attributed to high-risk population groups and improve patient outcomes following inpatient hospitalization:

- Identify historically disadvantaged populations that have been disproportionately burdened by the impact of social risk factors.

- “Support ongoing hospital quality improvement initiatives by providing data with which to stratify patient risk and organizational performance.”

- Encourage “meaningful collaboration between healthcare providers and community-based organizations.”

- Implement and evaluate “related innovations in health and social care delivery.”

- “Enable systematic collection of [health-related social need] data which aligns with” other efforts, such as CMS’ Medicare Advantage and Part D rule “in which we proposed that all Special Needs Plans (SNPs) complete health risk assessments (HRAs) of enrollees that include specific standardized questions on housing stability, food security, and access to transportation.”

- Improve “the accuracy of high-risk prediction calculations.”

- “Guide future public and private resource allocation to promote targeted collaboration between hospitals and health systems and appropriate community-based organizations.”

However, because the screening tool recommended to fulfill this new requirement does not capture the context or source of transportation barriers, it is insufficient to identify populations that have been disproportionately burdened by the impact of transportation barriers and insufficient to guide public and private resource allocation to address the root causes of transportation barriers.

Big Change 3: 2022 Joint Commission Requirement for Social Need Screening

In June 2022, the Joint Commission established new requirements to reduce health care disparities, which include social need screening.

Although not a federal action, this is a national action.

The Joint Commission is an independent, not-for-profit health care accrediting body.

“Approximately 80% of the nation’s hospitals are currently accredited by The Joint Commission, and approximately 85% of hospitals that are accredited in the U.S. are accredited by The Joint Commission,” according to The Joint Commission.

Their new requirement is part of the leadership chapter and focuses on fundamental processes.

The exact requirement is “the [organization] assesses the [patient’s] health-related social needs and provides information about community resources and support services.” Organization refers to “organizations in the Joint Commission’s ambulatory health care, behavioral health care and human services, critical access hospital, and hospital accreditation programs.”

Examples of social needs may include access to transportation, difficulty paying for prescriptions of medical bills, education and literature, food insecurity, and housing insecurity.

This went into effect in January 2023.

“Organizations need established leaders and standardized structures and processes in place to detect and address health care disparities,” The Joint Commission requirement states. “These efforts should be fully integrated with existing quality improvement activities within the organization like other priority issues such as infection prevention and control, antibiotic stewardship, and workplace violence.”

There are three important things to note with this requirement.

First, the requirement is to screen a representative sample of patients rather than all patients.

Second, although the requirement is to screen patients for the most common health-related social needs, it does not specify which social needs.

Third, the requirement does not provide the specific screening tools or questions to assess patients for social needs.

In other words, The Joint Commission requirement provides flexibility on which patients to target, which social needs to assess, and which methods to use to assess social needs.

Like the two CMS final rules previously explained, this flexibility fails to give transportation the attention it deserves as a health-related social need.

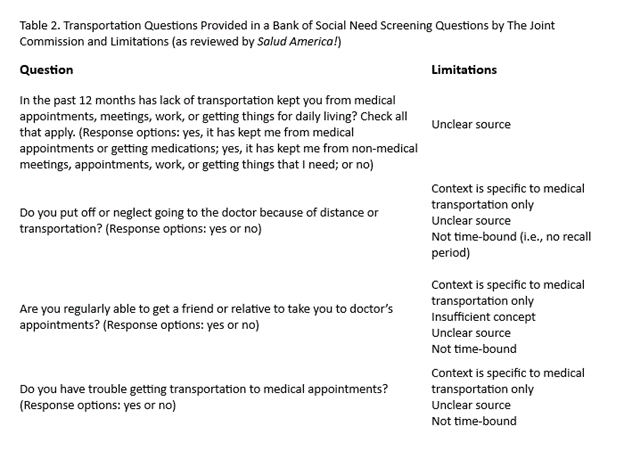

Related, although the publication date is unclear, The Joint Commission provides a bank of social need screening questions, which includes four transportation-specific questions. See Table 2 for the questions and the limitations we identified per our preliminary review in terms of concepts, contexts, and sources.

Related, although the publication date is unclear, The Joint Commission provides a bank of social need screening questions, which includes four transportation-specific questions. See Table 2 for the questions and the limitations we identified per our preliminary review in terms of concepts, contexts, and sources.

Again, regarding concepts, because transportation needs/barriers is an abstract concept, adequate conceptualization is necessary to identify and capture information about the most relevant aspects of this concept. Regarding context, because both medical and non-medical transportation impact health outcomes, it is important to capture information about both as distinct contexts. Regarding sources, it is important to understand the sources of transportation needs/barriers to inform interventions, investments, and policy changes that address the root causes of transportation needs/barriers to prevent them from arising in the first place.

Big Change 4: Accountable Health Communities (AHC) Model

Encouraging providers to screen patients for health-related social needs was not new for CMS in 2022 when they passed the final rules as explained above.

In 2017, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (Innovation Center) launched the Accountable Health Communities (AHC) Model to test the impact of assessing and addressing the health-related social needs of Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries in over 600 clinical sites in 21 states.

This was “one of the first federal pilots to systematically test whether identifying and addressing core [health-related social needs] improves healthcare costs, utilization, and outcomes,” according to the CMS’ IPPS Final Rule.

The pilot was disrupted by but continued through the COVID-19 pandemic.

Under the model, Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries at participating clinical sites were screened for five core health-related social needs (i.e., housing instability, food insecurity, problems with transportation, difficulties with utilities, and interpersonal violence). If positive, received a community service referral or community service navigation.

Accountable Health Communities (AHC) Model Five-Year Evaluation Report

In May 2023, the Innovation Center released its five-year evaluation report of the Accountable Health Communities (AHC) Model.

The Innovation Center found that 57% of the roughly one million Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries that were screened for the five core health-related social needs had two or more core needs.

Beneficiaries with just one social need were eligible for community service navigation if they also self-reported having two or more emergency department visits in previous 12 months.

More than three-quarters of eligible beneficiaries agreed to navigation.

To systematically evaluate whether screening and navigation resolves social need and improves healthcare costs, utilization, and outcomes, the Innovation Center used random assignment to create a control group that was offered a community referral and an intervention group that was offered a community referral and navigation.

“The strength of the similarities between the intervention and control groups suggests that randomization was successful in producing two samples for which the only salient difference is that the intervention group received navigation services while the control group did not,” the report states.

The results of the AHC Model were not what they expected.

When evaluating the AHC Model, the Innovation Center found that:

- Screening and navigation did not markedly increase beneficiaries’ connections to community services.

- Screening and navigation did not markedly increase resolution of beneficiaries’ health-related social needs.

- Screening and navigation did not markedly improve beneficiaries’ health care costs, service utilization, or health outcome

The AHC Model Did Not Markedly Increase Connection to Community Services

The AHC Model did not markedly increase connection to community services.

The Innovation Center suggests this is because the availability of community resources varies greatly and there are gaps between community resource availability and beneficiary needs.

The evaluation report explains that “beneficiaries experienced four key challenges to using community services: lack of transportation, ineligibility for services, long wait-lists, and lack of community resources (e.g., housing vouchers, utility assistance).”

Notice that lack of transportation is not only one of the five core health-related social needs but is also a challenge to using community services to resolve health-related social needs.

“Before the pandemic, approximately 48% of eligible beneficiaries had a transportation need; the percentage dropped to approximately 40% following the start of the pandemic and then remained roughly steady through December 2021,” the report states.

Although transportation needs declined after the pandemic, food needs increased, and transportation was found to be a barrier for patients attempting to use community resources to resolve their food needs.

Unfortunately, because transportation needs/barriers have been understudied, we know very little about the sources of transportation barriers; how transportation needs/barriers co-occur with other health-related social needs, like food insecurity and unemployment; or how transportation needs/barriers hinder access to community services and resources.

Overall, both the lack of community services and lack of access to community resources hinders connection to community resources.

However, despite differences in availability of and access to community resources, community navigation did not improve connection to community resources.

The Innovation Center looked at differences within subpopulation groups, such as benefit type (i.e., Medicare, Medicaid, dual eligible); race/ethnicity; Area Deprivation Index (i.e., a composite measure of need including multiple sociodemographic characteristics, such as poverty, education, employment, housing, and transportation); reported housing need at screening; and reported food need at screening.

They found noteworthy but inconsistent differences for some subpopulation groups.

Although they identified transportation as a barrier to community resources, they did not look at reported transportation need at screening as a subpopulation group.

Race was the only subpopulation group where one group who received navigation was more likely to use community resources than the group who did not receive navigation. Black beneficiaries who received navigation used community services 5.4 percentage points more than those who did not receive navigation (p < 0.10).

The only other subpopulation with statistically significant differences in use of community resources was among the most disadvantaged communities as indicated by the Area Deprivation Index.

Contrary to expectations, among the most disadvantaged communities, beneficiaries who received navigation were less likely to use community resources than those who did not receive navigation. Disadvantaged beneficiaries who received navigation used community services 3.0 percentage points less than those who did not receive navigation (p < 0.05).

The AHC Model Did Not Markedly Increase Resolution of Social Needs

The AHC Model did not markedly increase resolution of health-related social needs.

Among beneficiaries with more than one core health-related social need, only 38% had at least one need resolved. Only 20% had all their needs resolved.

These findings are lower than expected given that the theoretical foundation of the AHC Model is that, upon identification of needs and navigation to community resources, patients will be able to resolve their needs.

Moreover, it is important to note that the resolution of needs cannot be solely attributed to navigation because some survey respondents who reported their needs as resolved did not use any community services.

For example, for four of the five core needs, more survey respondents reported their needs as resolved than reported using community services.

This means among the few who resolved their needs, some resolved their need without community services. They relied on family, friends, and case workers to address their needs rather than community services.

Again, there were noteworthy but inconsistent differences for some subpopulation groups, such as benefit type, race/ethnicity, and Area Deprivation Index.

Among those in the highest quintile for Area Deprivation Index, beneficiaries who received navigation were statistically significantly more likely to have resolved their transportation needs than beneficiaries who did not receive navigation. There were no differences between the intervention and control groups for those in the lower four Area Deprivation Index quintiles.

However, there were no differences across the Area Deprivation Index quintiles for the other four social needs.

This suggests that the AHC model had more favorable impacts on resolving transportation needs for those in the most disadvantaged communities but not on resolving housing, utilities, food, or interpersonal violence needs.

What is missing in this evaluation report is differences in number of health-related social needs by the Area Deprivation Index subpopulation group.

Although the Innovation Center acknowledged the lack of community services and lack of access to community services and analyzed differences between those living in disadvantaged areas and those not living in disadvantaged areas, they never reported differences in number of health-related social needs by the Area Deprivation Index subpopulation group.

Moreover, although they state in the report that they “expect [health-related social needs] to reoccur after resolution,” the Innovation Center never addressed the social risk factors that cause social needs to occur and reoccur.

The Innovation Center concludes that navigation alone may not be sufficient to resolve health-related social needs.

We think navigation to community services is likely not sufficient to resolve health-related social needs because this strategy does nothing to address the social risk factors that cause social needs from arising in the first place, such as the factors that make up the Area Deprivation Index.

While it is crucial to help patients meet their immediate social needs, this is a downstream strategy that should be layered with upstream strategies to reduce social risk factors and prevent social needs.

The AHC Model Did Not Markedly Improve Health Costs, Service Utilization, or Outcomes

The AHC Model did not markedly improve beneficiaries’ health care costs, service utilization, or health outcomes.

Despite that navigation did not markedly increase connection to community resources or resolve health-related social needs, screening and navigation may have been effective in reducing emergency department visits among Medicare beneficiaries, but not Medicaid beneficiaries.

Based on stakeholder interviews, the Innovation Center suggests the following three reasons could explain reduced emergency department use:

- “The screening and navigation process created trust, which they could build on to help patients better navigate the health care system.”

- “Providing practical assistance, such as transportation to appointments, increased patients’ compliance with their health care plans thus reducing their reliance on the emergency department.”

- “Exposure to navigation services improved beneficiaries’ ability to navigate the health care system in other ways.”

The Innovation Center also evaluated if navigation impacted utilization of other health services as well health care costs and health outcomes. But they did not find statistically significant differences between beneficiaries who received navigation and those who did not receive navigation.

For example, there were no differences between the intervention group and control group in total expenditures, inpatient admissions, share of beneficiaries who received treatment for respiratory illness, or share of beneficiaries who were newly treated with an antidepressant medication.

Again, there were noteworthy but inconsistent differences for some subpopulation groups, such as benefit type, race/ethnicity, and Area Deprivation Index.

For example, non-White and/or Latino Medicare beneficiaries had larger reductions in both total Medicare expenditures and emergency department (ED) visits than White Medicare beneficiaries, suggesting that the model had more favorable impacts for non-White and/or Latino Medicare beneficiaries relative to non-Latino White Medicare beneficiaries, the report states.

However, this was not true for Medicaid beneficiaries.

Non-White and/or Latino Medicaid beneficiaries had a statistically significant smaller reduction in ED visits than non- Latino White Medicaid beneficiaries.

Another example is that Medicaid beneficiaries with multiple health-related social needs had larger reductions in both total Medicaid expenditures and ED visits than Medicaid beneficiaries with one health-related social need.

This suggests that the model had more favorable impacts for Medicaid beneficiaries with multiple health-related social needs relative to Medicaid beneficiaries with one health-related social need.

Although the Innovation Center concludes that “the AHC Model would not be expected to have the same impact on all subpopulations,” they are unable to explain the differential impacts across subpopulation groups. They suggest it may be related to variation across the 28 participating bridge organizations rather than to variation in social risk factors.

One limitation of this evaluation report is the emphasis on individual-level social needs without understanding community-level social risk factors.

The result is a somewhat simplistic conceptualization of health-related social needs as temporary, isolated, and resolvable through individual-level connection to community services rather than as lasting, co-occurring, and resolvable through community-level interventions to reduce social risk factors.

Again, while it is crucial to help patients meet their immediate social needs, this is a downstream strategy that should be layered with upstream strategies to address the social risk factors that cause social needs from arising in the first place.

Elevating Transportation as a Foundational Social Need

The examples above demonstrate two main shortcomings in the growing support for addressing SDoH and social need screening programs.

First, there is an overall lack of consensus on methods to assess transportation as a health-related social need. Moreover, there is a lack of evidence regarding the validity and reliability of methods to assess transportation needs/barriers.

Second, there are glaring limitations in the questions commonly used to capture information about transportation needs/barriers.

Within this second shortcoming, there are three key limitations.

The first limitation is that the conceptualization of transportation needs/barriers is often lacking consideration of more relevant aspects of the lived experience with, adaptations to, and impacts of transportation needs/barriers, such as not being able to go where you need to go or giving something else up to go where you need to go.

For example, capturing information about confidence using public transportation is capturing information about a minor inconvenience rather than a major obstacle, such as not being able to go where you need to go because of infrequent transit service with limited coverage, limited evening and weekend hours, and lengthy transfers. Additionally, confidence using public transportation is one minor aspect of the overall experience of transportation needs/barriers.

Similarly, getting “a friend or relative to take [them] to doctor” or “trouble finding or paying for transportation” are also minor aspects of the overall experience of transportation needs/barriers.

The second limitation is the lack of information about the context in which people experience transportation needs/barriers, particularly the lack of distinction of both medical and non-medical transportation needs/barriers.

For example, only providing yes or no response options to the question “has lack of reliable transportation kept you from medical appointments, meetings, work or from getting things needed for daily living?” fails to make the distinction between medical and non-medical transportation.

The third limitation is the lack of information about the specific and unique sources of transportation needs/barriers.

For example, capturing information about “lack of transportation” or “distance or transportation” fails to provide the information necessary to inform either downstream interventions or upstream investments and policy changes.

Given the growing emphasis nationwide on SDoH screening for and addressing health-related social need in health care, we need valid and reliable measurement instruments to assess transportation needs and barriers.

Given the limitations we identified in our preliminary review of the four recent big changes, the first necessary step is assessing the operational definition of transportation needs/barriers particularly in terms of transportation as a health-related social need.

Only then can we truly be ready to address transportation as a foundational social need.

Explore More:

Transportation & MobilityBy The Numbers

27

percent

of Latinos rely on public transit (compared to 14% of whites).