Share On Social!

Florida reinvented how they implement Complete Streets a few years ago, even adding coordinators to help each district create roads for people who travel by foot, bike, car, and more.

And they didn’t forget about public transit.

In fact, the Florida Department of Transportation’s (FDOT) created a guidebook to instruct and show examples of how to make public transit─trains, buses, & trolleys─a big part of Complete Streets.

Read more below in Part 2 of Salud America!’s three-part series on transportation changes in Florida. Part 1 examined Florida’s reinvention of Complete Streets. Part 3 will cover pedestrian death reduction.

Integrating Transit and Complete Streets

Complete Streets can save lives by providing safe options for people to walk, bike and use public transit. They also reduce car dependence and greenhouse gas emissions, promote economic development, and improve physical and mental health.

However, few Complete Streets projects properly integrate transit and vice versa.

Many of these projects are short term and focus on bicyclist and pedestrian issues, and don’t spend enough time considering transit.

FDOT’s Transit Office wanted to address this shortfall.

So they reviewed over 50 Complete Streets resources and examined over 30 projects, agencies, and communities demonstrating success in integrating transit and Complete Streets.

In 2018, they released their guidebook, A National Synthesis of Transit and Complete Streets Practices, to help transportation practitioners understand what it means to integrate transit and Complete Streets, the possible integration practices, and the important lessons from communities across the country.

They found that more than 1,300 jurisdictions have adopted Complete Streets policies. But only a few transit agencies have their own Complete Streets policies.

Low transit integration could be due to higher capital and operating costs, complex funding sources and infrastructure requirements, availability of funding, and involvement of more stakeholders.

They also found two important project categories for integration practices: new transit investments and roadway improvement projects in areas with existing transit.

“These two project categories represent different approaches to project leadership (transit agency versus municipal authority), project workflow (transit-focused mobility versus transit-enabled access), and investment (high versus comparatively low),” the guidebook states.

‘Context Classification’ Helps Transit in Florida

Beyond project categories, integration practices exist for different planning, design and construction phases, as well as for different land use context and characteristics.

FDOT concluded that their new context classification system is an opportunity for integrating transit and Complete Streets.

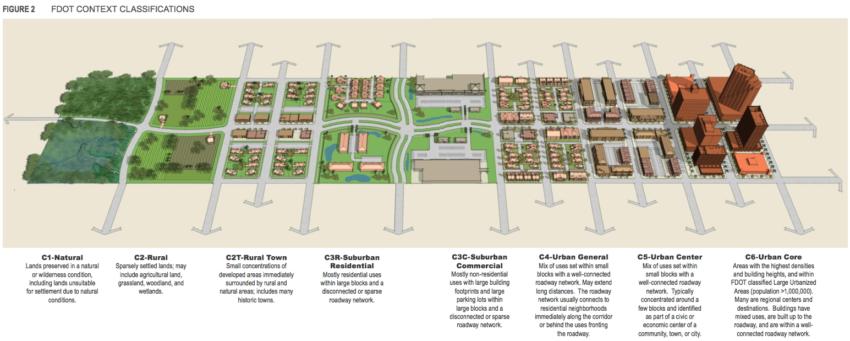

Context classification considers the various built environments existing in Florida, like natural, rural town, suburban commercial, and urban core, to determine roadway users, regional and local travel demand, and challenges and opportunities of each roadway user.

The context classification system provides a framework for roadway design criteria and standards according to land use context and characteristics, which is useful for identifying opportunities to integrate transit.

FDOT’s guidebook also provides examples of specific integration practices in nine communities and contexts.

The FDOT Transit Office team explored nine case studies across the country to define what is meant by transit and Complete Streets integration, what are the practices that can help do so, which ones are particularly applicable in Florida, and what are the lessons learned.

A Model Case Study: Phoenix

In Phoenix, Arizona (41.8% Latino), development driven by light rail has exceeded $8 billion, according to the guidebook.

It started in 2003, when the City adopted a Transit Oriented Development (TOD) Overlay Zoning District to encourage mixed-use development within one-quarter mile of the anticipated light rail system.

In 2007, the City developed a policy toolbox to assist municipalities, property owners and developers to coordinate pedestrian-friendly mixed-use near station areas.

“Transit spurs development, and development spurs transit,” the guidebook states.

In 2014, Phoenix adopted a Complete Streets Ordinance to create a multimodal network that provides accessibility and circulation to facilitate active transportation and public health.

Since then, an epic partnership between the City of Phoenix, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Arizona State University, Vitalyst Health Foundation, and others are working toward walkable communities connected to light rail.

A Model Case Study: Cleveland

In Cleveland, Ohio (10.8% Latino), the 7.1-mile Healthline Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) corridor has attracted $5.8 billion in investment, according to FDOT’s guidebook.

“After failure to secure funding for a subway system, rail network, or electric trolley line, City officials decided to pursue (BRT) as an affordable and realistic solution,” the guidebook states.

However, fearing stigma, the development community initially opposed buses.

Over 2000 public meetings were held with involvement from 80 stakeholders from civic, university, business, social, neighborhood and government organizations to gain community perspectives and emphasize how BRT could support economic development, improve pedestrian safety, and increase livability.

BRT won, thus Cleveland won.

In 2004, the City adopted the updated master plan; in 2005, the City adopted the area’s new transit supportive zoning code; and in 2007, the City updated the master plan to prioritize TOD along the corridor.

“Implementation was made possible by a complex funding partnership of multiple organizations, including the GCRTA as the project sponsor, the FTA New Starts program, the Ohio DOT, the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency, and the City of Cleveland, as well as the Cleveland Clinic and University Hospitals – the city’s two biggest employers – who purchased naming rights in a 25-year deal,” the guidebook states.

In 2008, the $200 million, 7.1-mile Healthline BRT opened.

In 2011, the City passed a Complete and Green Streets ordinance, with a focus on sustainable policies to reduce environmental impacts.

The coordination of land use planning and transportation planning in the redesign of the street and sidewalk areas along the Healthline BRT corridor created connected, vibrant and safe spaces that provide mobility choices, improve quality of life, increase property values, enhance transit hubs and offer a more livable corridor.

Over 1,500 trees were planted; public art installations were integrated into street design; lighting and shelters reflect the neighborhood, and buses travel at 35 mph in their dedicated lanes while normal traffic is limited to 25 mph.

According to the guidebook, for every dollar spent on the Healthline BRT, the return on investment is approximately $114, and the number of jobs along the corridor nearly doubled in the first five years.

“The Healthline is an example of how BRT can help to revitalize city centers, speed commutes, improve air quality, and leverage investment and development near transit,” said Walter Hook of ITDP, according to the guidebook. “We consider the Healthline to be a best practice for BRT in the US, and our hope is that it encourages other US cities to adopt this cutting-edge form of mass transit.”

Watch a video about how bus rapid transit and Complete Streets improvements helped transform Cleveland.

A Model Case Study: Jacksonville

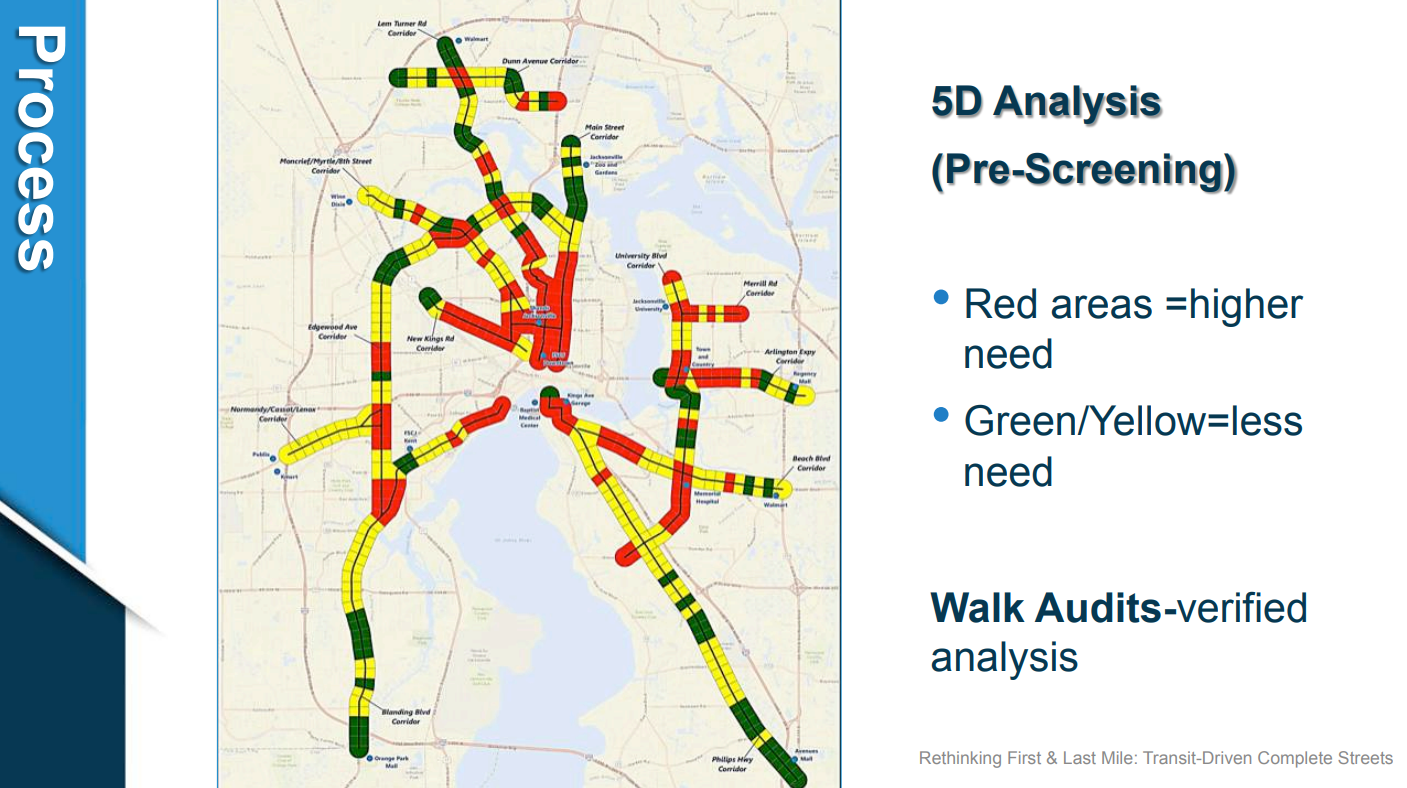

Back to Florida, the Jacksonville Transportation Authority (JTA) focuses Complete Streets work within one-quarter- to one-half-mile of the region’s high-ridership corridors to improve first mile/last mile connections to transit.

“JTA recognized that for the City of Jacksonville to build its public transportation ridership, JTA had to shift its focus from moving people out of cars and onto public transportation, a strategy that was neither realistic nor particularly effective for a region as spread out as Jacksonville,” according to the guidebook. “Instead JTA had to focus on capturing the transit dependent population that was not taking advantage of the public system.“

In 2014, City Council voted to extend the local gas tax which would generate $100 million over the next five years, with a portion of the revenue going towards pedestrian and bicycle improvements.

In 2015, JTA introduced Mobility Corridors, a program to invest in projects that facilitate walking, biking, and riding on 70 miles of Jacksonville’s transit network.

They hosted community charrettes and conducted walking audits to examine the associations between safety, access to healthy foods, and other quality of life factors.

JTA started small with “quick fix” projects to provide immediate safety and operational improvements at a lower cost, and identified more substantial “keystone” projects to showcase Complete Streets and build momentum for more advanced projects.

The program signaled a shift in the planning of roadways: pedestrian, bicycle, and transit accommodations are “no longer merely viewed as ‘amenities’ to be added when feasible, but central to the design process,” according to the guidebook.

You can learn more about JTA’s efforts in this Complete Streets webinar, “Rethinking First & Last Mile: Transit-Driven Complete Streets.”

Complete Streets and transit integration is particularly relevant in Florida, as Florida voters passed two of two public transportation ballot measures during the 2018 midterm election cycle—Tampa and Broward County. Nationwide, voters passed 17 of 20 public transportation ballot measures—two remain undecided. That’s an 85% approval rate.

Read more about these three case studies and six others in FDOT’s guidebook, A National Synthesis of Transit and Complete Streets Practices.

Complementary to initiatives to support the Complete Streets Policy, FDOT also adopted new safety performance targets.

Learn more in the rest of Salud America!’s three-part series on transportation changes in Florida.

Part 3 will be out Dec. 7. Part 1 was released Nov. 28.

Explore More:

Transportation & MobilityBy The Numbers

27

percent

of Latinos rely on public transit (compared to 14% of whites).