Share On Social!

How is your neighbor doing during the coronavirus pandemic?

In the Boston area, Anna Kaplan, Jessie Norriss, Sophia Grogan, and other neighbors saw their neighbors lose jobs, with no money for bills or groceries. They saw college students and non-English speakers get no support.

They each wanted to help their neighbors.

So, together, they helped create Mutual Aid Medford and Somerville (MAMAS), an on-the-fly mix of multilingual online documents, Google maps, social media, and text-message threads where neighbors can offer to help, and/or ask for help with grocery deliveries, filing for unemployment, emotional support, and more.

Since March 12, 2020, MAMAS has connected over 1,000 neighbors to each other and raised over $90,000 to meet needs.

And, weirdly, it all started with a snow-shoveling fail.

Neighbors Shoveling Snow for Neighbors

Snow often blankets Boston each winter.

As the snow falls, older folks and those who work multiple jobs often can’t meet legal requirements to shovel snow.

In December 2019, Grogan and their friends had an idea.

They planned out a “snow-shoveling brigade,” where neighbors would volunteer to shovel snow for their elderly neighbors.

“Folks in New England have to shovel their snow—they legally have to do it—but there is no service to do it and some people can’t afford to pay people to do it,” Norriss said. “This would be a way to help.”

But winter was mild. No brigade was needed.

But winter was mild. No brigade was needed.

Little did Kaplan and Norriss know that a fiercer threat would arrive in 2020.

The Rise of Coronavirus in the Boston Area

Medford (5.3% Latino) and Somerville (10.8% Latino) are home to a diverse population, said Kaplan and Norriss.

They have an older white working class. Students from around the world who study at Boston universities. People who commute to and from Boston’s biotech field. Pockets of immigrants from many countries speak over 80 languages. More affluent residents who have displaced long-time residents.

In March 2020, the coronavirus pandemic struck all these groups.

Across the country, COVID-19 is worsening historical inequities, and disproportionately affecting and killing Latinos and others of color.

In Boston, African-Americans are overrepresented in coronavirus cases (40% of cases; 25.3% of city population), compared to Latinos (19%; 19.7%), Asians (3%; 9.6%), and Whites (27%; 52.6%), according to city data on May 1, 2020.

Kaplan saw on-the-ground impact right away.

Kaplan saw on-the-ground impact right away.

Schools closed. University students who came to Boston from around the U.S. or abroad suddenly had to leave their dorm with nowhere to go.

Businesses laid off workers.

“Very rapidly, people who were in the service industry, restaurants, hotels, lost their jobs and their healthcare,” she said. “98% of the members in the local union lost their positions.”

People living paycheck to paycheck, parents, and the elderly struggled as inequities worsened, Norriss said.

“We saw people asked to stay home, but no plan to get groceries to those particularly vulnerable,” she said. “Parents don’t have access to schools or day cares. There was no communication about the virus, quarantining.”

Kaplan added: “There was just a sort of void of any kind of systematic response.”

That’s when they thought back to their snow-shoveling idea.

The Idea for a Mutual Aid Network in Medford and Somerville

Months after Mother Nature scrapped their plan to create a volunteer network to shovel snow, Grogan and her neighbors applied their help-your-neighbor idea to the new pandemic.

Their concept—mutual aid—is the grassroots provision of person-to-person community assistance through a centralized system.

The aim is to build strong connections for assistance among neighbors. It recognizes everyone has something to offer, and everyone has things they need.

So a core group of neighbors, eventually including Kaplan and Norriss, got busy organizing a mutual aid network.

So a core group of neighbors, eventually including Kaplan and Norriss, got busy organizing a mutual aid network.

While individually self-quarantining, the core team called people they knew. They started a Google document to list and pool local resources. Started a Venmo account to accept donations. Started a Facebook page to spread the word.

Soon, MAMAS (Mutual Aid Medford and Somerville) was born.

The Ways MAMAS Empowers Neighbors to Help Each Other Out

MAMAS has lots of moving parts, built on the fly:

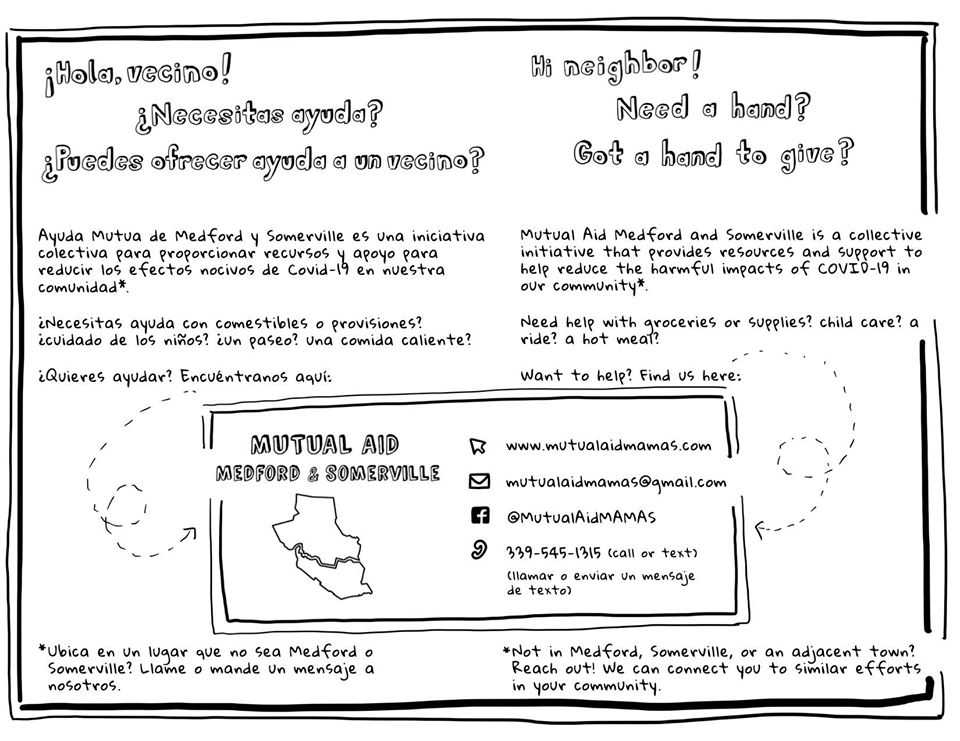

Website in English (mutualaidmamas.com) and Spanish (https://mutualaidmamas.com/home-2).

The website has forms people can fill out to ask for, or offer, support.

“People can fill out a form that walks them through requests they might have for finances, needing groceries, supplies, masks, housing, child care, or needing emotional peer support,” Norriss said.

“People can fill out a form that walks them through requests they might have for finances, needing groceries, supplies, masks, housing, child care, or needing emotional peer support,” Norriss said.

A hotline to call or text to request aid (339-545-1315).

The hotline is staffed by neighbors who volunteer to take calls in 3-hour shifts between 9 a.m. and 9 p.m. ET.

The volunteers direct neighbors to resources, such as:

- Money

- Transportation

- Groceries

- Supplies

- Housing

- Storage

- Child care

- Pet care

- Emotional support

- Translation

- Political education

- Accessibility

- Support for immigrants

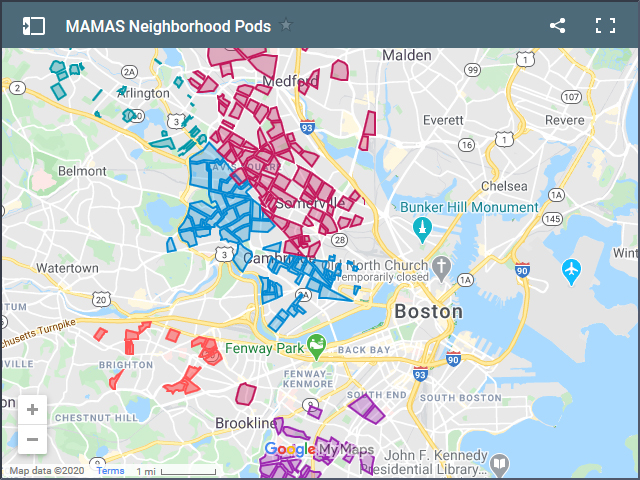

“Neighborhood pods” led by a local resident and connected by a text-message thread and pinpointed on a Google map.

Neighborhood pods are instrumental for MAMAS.

Using a Google form, they recruited volunteers to serve as pod leaders. As pod leaders signed up, Kaplan plotted their addresses as points on a map.

“I drew polygons around them for a two- to three-block radius, and tried to fill the two cities with neighborhoods pods,” Kaplan said.

“I drew polygons around them for a two- to three-block radius, and tried to fill the two cities with neighborhoods pods,” Kaplan said.

You can click on a pod where you live and ask the pod leader to add you to the group text for that pod. Or might ask the pod leader to coordinate support.

MAMAS now has over 100 neighborhood pods on the map.

“People in my pod have texted mostly offering help to each other,” Kaplan said.

A large group of neighborhood volunteers.

MAMAS is completely volunteer-driven.

They have no funding. Money raised through donations are redistributed to neighbors.

They have no funding. Money raised through donations are redistributed to neighbors.

“We have a large team of volunteers and Google groups of people who signed up to help, 300-400 people,” Norriss said. “They are providing tutoring to kids online, helping file for unemployment.”

Social media and print outreach.

MAMAS has a Facebook page.

They also created materials in a bunch of languages—English, Spanish, Portuguese, German, Creole, Polish, and more. They leave flyers to leave on doorsteps with the website and hotline.

“We’ve tried to build out as much a multilingual team as we could,” Norriss said.

How Is MAMAS Working So Far?

The first week in mid-March, MAMAS got five calls for help a day.

Now they get up to 20 calls, Kaplan said.

They connect non-citizens to immigrant rights groups. Others need help filing for unemployment. MAMAS helps make up to 20 grocery deliveries a day.

They also give money to neighbors to pay rent or prescriptions.

“We’ve redistributed $90,000 between March 12 and April 26,” Norriss said. “We see that as a huge success in the amount of giving among neighbors.”

Beyond the numbers, Kaplan and Norriss have plenty of heartwarming stories to share, too.

Like the time a Spanish-speaker called the hotline. They said they are not able to leave the house, but their 3-year-old had a birthday the next day.

The volunteer who took the call got a Spanish-speaker to call them back, and deliver a cake, ice cream, and balloons—within an hour.

“They shared pictures of the party,” Norriss said. “It was a beautiful story.”

One neighbor needed a laptop so their child could do school work from home.

Later, that neighbor volunteered to answer the hotline.

“The community of volunteers and those who receive support are the same community,” Kaplan said. “The people who receive money are the ones operating the hotline, which is a really key part of mutual aid.”

The core MAMAS team is still working hard, too.

“A lot of us still have full-time jobs, and we spend 2-4 hours a day [on the MAMAS network], if not more” Norriss said.

But they built the network so that other volunteers can step in to help.

“The whole thing isn’t built on one person, or a few people,” Kaplan said. “It’s leveraging the skills of the whole community. The structures are there to continue the work.”

The Future of MAMAS and Mutual Aid in Other Places?

Mutual aid can’t replace swift governmental action to provide a safety net, or a strong plan to ensure health equity.

But, in a health pandemic like COVID-19, mutual aid groups are “uplifting” and “life-changing,” wrote

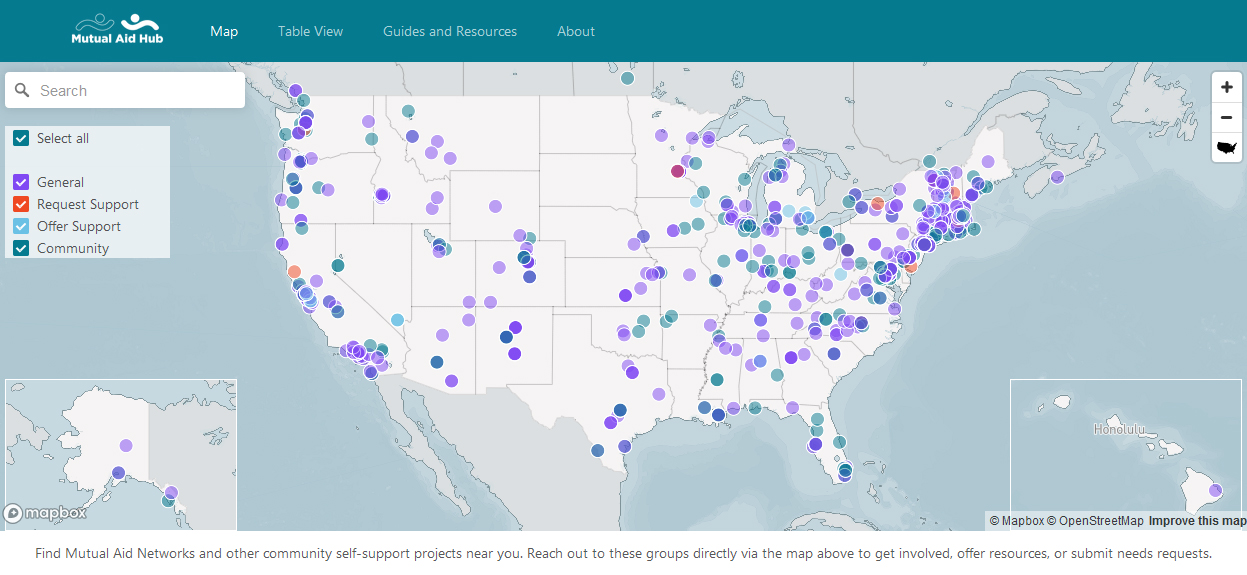

“Hundreds of networks like [MAMAS] have popped up all over the country in response to the coronavirus pandemic,”

The Mutual Aid Hub lists over 750 of these groups across the country.

The Mutual Aid Hub lists over 750 of these groups across the country.

Mutual aid is even happening in Puerto Rico.

“We created Mutual Aid Hub to highlight the incredible work of mutual aid organizers around the country, and to facilitate connections and shared strategies in this growing movement of community support,” according to the nonprofit Town Hall Project.

Back in the Boston area, Kaplan and Norriss want to help spread mutual aid across the country.

They created a replication document to help others learn from and adapt MAMAS to their community.

“Everything that we’ve done has been through Google documents, so it can be shared, copied, and replicated,” Norriss said. “One thing we really try to emphasize is our vision and values, and try to maintain that in the replication.”

Norriss also said they want to sustain MAMAS for a long time.

“Our goal is to build an infrastructure that lasts beyond COVID, and realize that we want to be connected to our neighbors,” she said.

Kaplan agreed.

“COVID isn’t the only crisis our communities have faced,” she said. “The reality is, every month, there are families who can’t pay rent, and they deserve a place to live.”

“I hope our structure can last beyond this moment, to help these families.”

By The Numbers

23.7

percent

of Latino children are living in poverty

This success story was produced by Salud America! with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The stories are intended for educational and informative purposes. References to specific policymakers, individuals, schools, policies, or companies have been included solely to advance these purposes and do not constitute an endorsement, sponsorship, or recommendation. Stories are based on and told by real community members and are the opinions and views of the individuals whose stories are told. Organization and activities described were not supported by Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and do not necessarily represent the views of Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.