Share On Social!

The U.S. has a violent child death problem.

Developing strategies to prevent violent child death from firearms and traffic crashes is a demanding task that requires consideration of numerous upstream, interrelated, and tangential issues.

To help safety advocates develop strategies to prevent violent child death, we compiled five frameworks to help:

- Understand and explain how proposed strategies will prevent violent child death

- Layer multiple strategies to cover shortcomings in strategies

- Prioritize upstream primary prevention strategies to improve outcomes for entire populations

- Consider the level of intrusiveness of strategies

- Apply racial equity tools to ensure equitable adoption/implementation of strategies

The five frameworks include:

- Logic Model/Theory of Change

- The Swiss Cheese Model of Risk Reduction

- Three-Level Preventions Strategies

- The Ladder of Intervention

- Racial Equity Assessment Tools

Salud America! is exploring violent child death in a four-part series, to include defining and monitoring the problem and identifying risk and protective factors.

Here we examine five prevention frameworks to help local, state, and federal leaders develop and advocate for upstream strategies to prevent violent child deaths death from firearms and traffic crashes.

Framework 1 for Preventing Violent Child Deaths: Theory of Change Logic Model

Theory of change logic models are used as visual tools to present the logic or rationale for how proposed strategies will address social problems, such as death and injury from firearms and traffic crashes.

Traditionally used in public health, basic logic models specify the relationships among goals, interventions, and outcomes, often with a focus on the nuts and bolts of downstream programs.

They visually reflect the resources, inputs, outputs, and expected outcomes of the proposed program.

However, as will be explained further throughout this post, it is important to think beyond the downstream programs that focus on social needs and prioritize upstream strategies that prevent those social needs from arising in the first place.

That’s where the more specific theory of change logic model can help.

Beyond a basic logic model, a theory of change logic model calls for consideration of bigger theoretical ideas to understand and explain how proposed strategies will produce expected outcomes.

This is a five-step process that requires identification of and discussion about:

- The root causes of the problem, to include the root causes of the risk factors rather than just the risk factors themselves

- Layering various prevention strategies (which will be discussed in following four frameworks)

- Where the proposed strategies fit into the vast sphere of numerous public policy, institutional, organizational, community, and individual factors that also impact the problem

- The potential barriers that stand in the way of prevention strategies

- The underlying values, beliefs, and assumptions regarding both the problem and the proposed strategies

Understanding and explaining how proposed strategies will produce expected outcomes requires identification of the root causes of both the problem and its risk factors.

See our previous two posts in this series about identifying the problem and identifying risk factors for the problem.

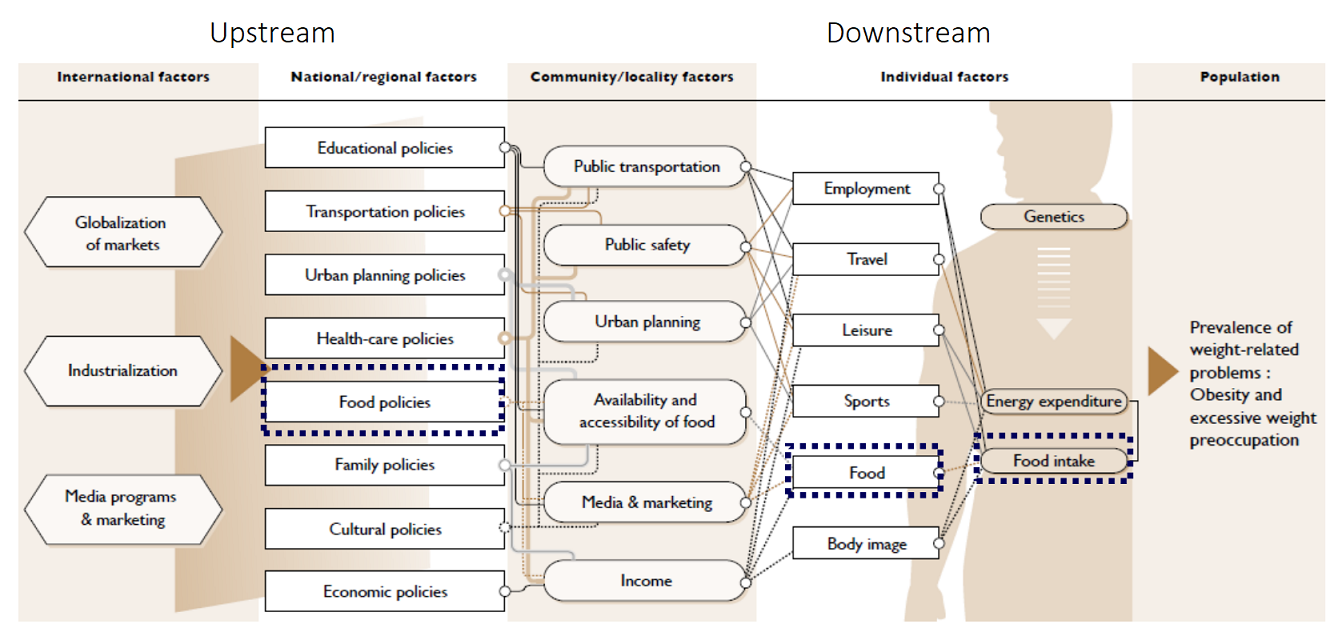

Thus, understanding and explaining how proposed strategies will produce expected outcomes requires identification of where your proposed strategies fit into the broader context of numerous other factors that impact the problem, to include public policy, institutional, organizational, community, and individual factors.

This may require the development of a causal model of factors.

For example, see the image of a causal model of factors influencing weight-related problems, which was created alongside a theory of change logic model for nutrition labeling policies by the National Institute of Public Health Quebec. We modified it by adding upstream and downstream. Notice the dotted boxes which indicate where nutrition labeling policy and its effects fit in.

While a comprehensive theory of change logic model may demonstrate the relationship between nutritional labeling policies and the expected outcome to prevent obesity, when considering the numerous other factors that impact obesity, it is apparent that nutritional labeling policies alone may have a limited impact if nothing else changes.

Developing a causal model of factors is an important exercise to help visualize where the proposed strategies fit into the broader context of the problem and to help focus discussion around the most upstream and meaningful strategies, for which the following four frameworks will help you develop.

Understanding and explaining how proposed strategies will produce expected outcomes also requires identification of the potential barriers that may hinder adoption/implementation.

Barriers can be related to policies, practices, and systems for which a systems-thinking approach should be applied to map out the key agencies, organizations, and individuals whose actions—and inactions—influence those policies, practices, and systems.

The causal model of factors will further support this step.

Barriers can also be related underlying values, beliefs, and assumptions that justify existing policies, practices, and systems.

Thus, understanding and explaining how proposed strategies will produce expected outcomes also requires identification of and discussions about the underlying values, beliefs, and assumptions of both the problem and the proposed strategies.

These discussions can be complicated because they require a critical systems-thinking approach to examine and critique systems and structures.

In addition to mapping out the key agencies, organizations, and individuals whose actions influence the broader systems that encompass child firearm deaths and child traffic deaths, there is a need to also identify and acknowledge how underlying values, beliefs, and assumptions influence those agencies, organizations, and individuals.

This is particularly relevant when considering support/opposition for existing/proposed strategies.

Explained in more detail below, the Three-Levels of Prevention Strategies can support this step by considering the upstream strategies necessary to address the root causes.

Also explained in more detail below, the Ladder of Intervention can support this step by considering the level of intrusiveness of each strategy. After all, strategies that intrude on personal freedom—real or perceived—are likely to garner opposition.

Therefore, not only does a theory of change logic model include the specific strategies to address the root causes of the problem, it also includes tangential strategies to address systemic barriers and underlying values, beliefs, and assumptions.

These are known as preconditions.

Preconditions are based on the theoretical foundations of the strategies. They are the conditions required to overcome barriers and assumptions to adopt/implement the strategies and set off the domino effect necessary to achieve early, intermediate, and ultimate outcomes.

“A more complete theory of change articulates the assumptions about the process through which change will occur, and specifies the ways in which all of the required early and intermediate outcomes related to achieving the desired long-term change will be brought about and documented as they occur,” according to The Community Builder’s Approach to Theory of Change.

Overall, theory of change logic models should visually reflect barriers, assumptions, strategies, preconditions, and early, intermediate, and ultimate outcomes.

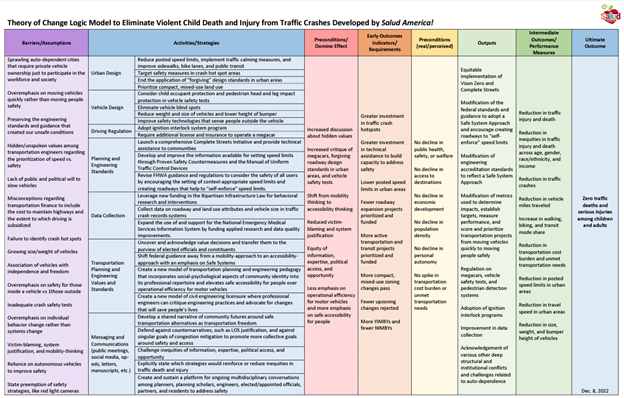

Theory of Change Logic Model Example. Amanda Merck, digital content curator at Salud America! at UT Health San Antonio, and Dr. Amelie G. Ramirez, director of Salud America! at UT Health San Antonio, developed a working draft of a Theory of Change Logic Model to Eliminate Violent Child Death and Injury from Traffic Crashes.

Although you will find specific examples of barriers, assumptions, strategies, preconditions, and outcomes in our working draft, they are too broad for any one agency or organization to adopt.

Although you will find specific examples of barriers, assumptions, strategies, preconditions, and outcomes in our working draft, they are too broad for any one agency or organization to adopt.

Rather, this is an overarching theory of change logic model with a variety of elements that will be relevant to various agencies, organizations, and individuals whose actions influence the broader system that encompasses child traffic deaths across local, regional, state, and federal levels.

Below is a brief narrative specific to one strategy that can be traced through our working draft.

Regardless of mounting evidence, many cities across the country will struggle to adopt/implement specific safety strategies, such as, “reduce posted speed limits, implement traffic calming measures, and improve sidewalks, bike lanes and public transit,” as stated in our theory of change logic model.

One of the reasons cities will struggle is due to barriers related to an “overemphasis on moving vehicles quickly rather than people safely” in institutional policies and practices across local, regional, state, and federal levels.

Thus, a necessary precondition is “less emphasis on operational efficiency for motor vehicles and more emphasis on safe accessibility for people.”

To achieve this precondition, tangential strategies need to address transportation planning and engineering values and standards, such as “shift federal guidance away from a mobility-approach to an accessibility-approach with an emphasis on Safe Systems.”

This strategy will also contribute to other preconditions, such as “shift from mobility thinking to accessibility thinking,” which will support a domino effect to achieve early outcomes, such as “lower posted speed limits in urban areas” and “more active transportation and transit projects prioritized and funded.”

Although not relevant to all theory of change logic models, ours includes a second set of preconditions wherein agencies, organizations, and individuals see “no decline in public health, safety, or welfare” and “no decline in access to destinations.”

This second set of preconditions is necessary to maintain momentum and prevent opposition to adoption/implementation of the strategies.

If this second set of preconditions is not met, it may mean there were unintended consequences of the strategies thus the intermediate outcomes will likely not be achieved, and the ultimate outcome will likely not be achieved.

If this is the case, the barriers, assumptions, and strategies in the theory of change logic model may need to be modified.

Conversely, if this second set of preconditions is met, then the domino effect will continue until the intermediate outcomes are achieved. This will result in progress on the performance measures toward reaching the ultimate outcome, zero traffic deaths and serious injuries among children—and adults.

Two of the most helpful resources to develop a theory of change logic model are:

- The Community Builder’s Approach to Theory of Change: A Practical Guide to Theory Development from the Aspen Institute

- Constructing a Logic Model for a Healthy Public Policy: Why and How from the National Institute of Public Health of Quebec

Use caution when exploring resources to help you develop a theory of change logic model because many are too generic and focus on the nuts and bolts of downstream programs rather than big picture upstream policies. Additionally, many lack guidance to think through barriers and assumptions.

In summary, developing a theory of change logic model to understand and explain how proposed strategies will produce expected outcomes is an iterative process across the four steps mentioned above.

Thus, you will need the following four frameworks to continue developing prevention strategies for your theory of change logic model.

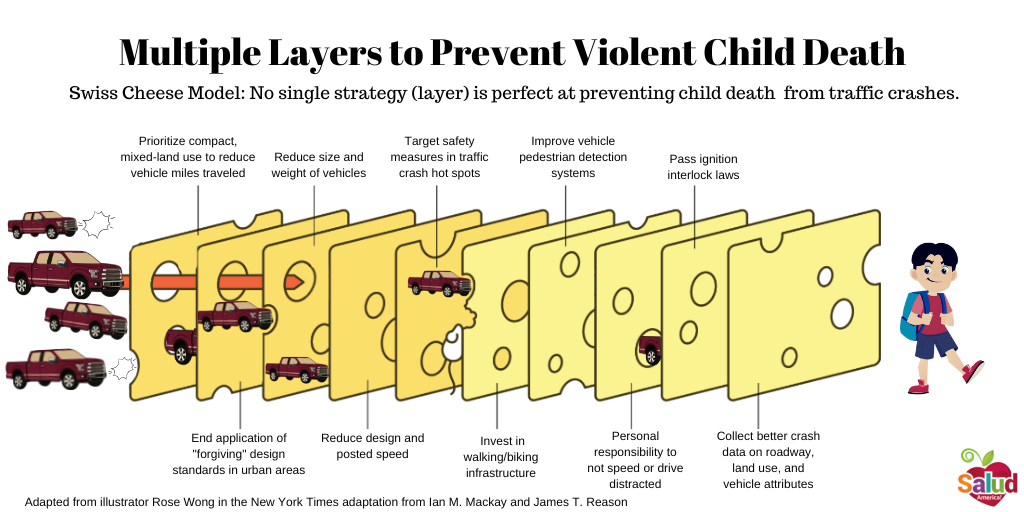

Framework 2 for Preventing Violent Child Deaths: The Swiss Cheese Model of Risk Reduction

When considering strategies to prevent violent child death, the Swiss Cheese Model of Risk Reduction offers a helpful visual depiction of how a variety of strategies are necessary to work together to prevent traffic deaths and firearm deaths.

Each strategy or intervention to address traffic deaths and firearm deaths has holes, like a slice of Swiss cheese, for which risk can slip through.

Multiple layers of strategies are needed cover the holes in other strategies, which reduces risk and increases protection.

For example, as mentioned previously in this series, although mass shootings with assault rifles have been on the rise and guns with high-capacity magazines led to six times as many people shot per mass shooting, mass shootings account for a small share of gun deaths.

Thus, many doubt the impact of banning or heavily regulating assault rifles without other strategies.

Moreover, many think these strategies infringes on their personal liberties.

This is an example of an intrusive primary prevention strategy, or “slice,” with holes. We will discuss primary prevention strategies and level of intrusiveness in further detail below.

Thus, discussions about banning or heavily regulating assault rifles should accompany more impactful and less intrusive primary prevention strategies.

The Swiss Cheese Model of Risk Reduction to Prevent Gun Deaths

Regarding firearm deaths, some of the “slices” could include:

- Personal Responsibility: Keeping guns locked to reduce access by unauthorized users and reduce the risk of misuse.

- Health Care: Health care providers, particularly pediatricians, screening about patients’ access to firearms and provide counseling to discuss risk factors and protective factors.

- Mental Health Care: Increasing access to mental health care for all Americans to identify and provide treatment for those at risk for violence due to mental illness, suicidal thoughts, or feelings of desperation.

- Perceptions of Masculinity: Providing programs in schools, workplaces, prisons, neighborhoods, and clinics to change perceptions among males of social norms about behaviors and characteristics associated with masculinity, such as violence, to reduce the prevalence of gun violence.

- Prevent, Detect, and Mitigate Toxic Stress: Adopting strategies in healthcare, social services, early childhood, education, and justice to prevent, detect, and mitigate toxic stress.

- Behavioral Threat Assessments: Conducting behavioral threat assessments in schools, colleges, and the workplace (public and private) to analyze if a person poses a threat and intervene to reduce the threat.

- Stop Perpetuating Segregation: Outlawing discrimination based on income, to include ending exclusionary zoning, such as single-family zoning, and eliminating lot size restrictions in urban areas, particularly near mass-transit hubs, to stop trapping low-income families in disadvantaged and low-opportunity neighborhoods.

- Stop Perpetuating Segregation: Requiring jurisdictions to develop plans to take meaningful actions to overcome patterns of segregation.

- Increase Opportunities for Affordable Housing: Investing in affordable rental housing and increasing access to affordable homeownership, to include affordable home construction and increasing access to affordable credit, particularly in high-opportunity neighborhoods.

- Firearm Sales Taxation: Taxing guns sales to deter gun sales.

- Firearm Sales Regulation: Prohibiting the sale of firearms to high-risk groups, such as domestic violence offenders, persons convicted of violent misdemeanor crimes, and individuals with mental illness who are risk to themselves or others to reduce threats.

- Firearm Sales Regulation: Close the private sale loophole and require unlicensed sellers to conduct a background check prior to selling.

- Firearm Sales Regulation: Banning assault rifles and high-capacity magazines.

- Firearm Laws: More strict enforcement of current firearm laws.

- Firearm Regulation: Enable federal extreme risk protection orders to temporarily restrict access to firearms for those identified by law enforcement, family, or physicians and deemed by civil courts as being high-risk for violence.

- Gun Dealers: Reforming or shutting down the “bad apple” licensed gun dealers, to include preventing the sale of guns to straw purchasers or gun traffickers, to reduce the supply of illegal guns.

- Gun Kits: Requiring commercial manufacturers of unserialized gun kits to become licensed and include serial numbers of the kits frame or receiver and requiring commercial sellers of these kits to become federally licensed and run background checks prior to a sale.

- Firearm Technology: Safety technologies that prevent unauthorized users from being able to fire weapons.

- Data Collection: Increasing investment in the study of risk patterns and preventive measures to prevent firearm deaths, to include socioeconomic, community, and policy factors.

- Data Collection: The National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS) database could provide more helpful data in that it collects State and Territorial EMS fatality and injury data from 911 calls.

- Criminal Laws: Repealing shoot first/stand your ground laws.

As an example, take how to try and stop the perpetuation of segregation.

Segregation from redlining alone does not lead to disparities in firearm violence, but it does lead to the downstream effects (poverty, poor educational attainment, high share of rental housing etc.) that are associated with firearm violence.

Thus, policymakers need to consider layering strategies/slices like this to address the overarching upstream problem, as well as the mediating problems.

In other words, although desegregation alone is not the solution, it is critical to layer upstream strategies/slices to desegregate housing/schools with strategies to reduce poverty, close the wealth gap, and improve access to homeownership.

If not, sustained segregation will continue to create the harmful downstream effects that contribute to firearm violence.

Regarding better data collection on firearm violence, “databases should classify the types of gun violence (suicides, intimate partner violence, mass shootings, interpersonal violence, police shootings, unintentional injuries) based on clearly defined and standardized definitions,” according to The Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence.

Some may argue against extreme risk protection orders, for example, because they don’t do anything to prevent unintentional gun injuries or to prevent at-risk individuals from purchasing a gun through an unlicensed dealer.

This is why extreme risk protection laws should be layered with other public health prevention strategies/slices to cover holes.

Similar to how auto manufacturers face regulations and fines regarding environmental protection, restaurants and stores face regulations and fines regarding the sale of alcohol to minors, and doctors and health clinics face regulations and fines regarding the prescription of controlled substance, it is reasonable to expect and demand regulations on the sale of guns.

It is important to point out that safety regulations on auto manufacturers are lacking.

The Swiss Cheese Model of Risk Reduction to Prevent Traffic Deaths

The U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) calls this Swiss cheese approach a Safe System approach.

“It works by building and reinforcing multiple layers of protection to both prevent crashes from happening in the first place and minimizing the harm caused to those involved when crashes do occur,” according to USDOT.

USDOT’s Safe System Approach includes key departmental actions across five objectives, safer people, safer roads, safer vehicles, safer speeds, and post-crash care. Specific actions include:

- Safer People: Leverage new funding in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law for behavioral research and interventions, and use education, technical assistance, and outreach to disseminate information to partners.

- Safer Roads: Complete the current rulemaking process for Manual Uniform Traffic Control Devices (the Manual) by finalizing the proposed amendments and incorporating changes based on the public comments and Administration priorities.

- Safer Roads: Launch a comprehensive Complete Streets Initiative and provide technical assistance to communities of all sizes to implement policies that prioritize the safety of all users in transportation network planning, design, construction, and operations, including in small towns and rural areas.

- Safer Vehicles: Initiate a new rulemaking to require Automatic Emergency Braking and Pedestrian Automatic Emergency Braking technologies on new passenger vehicles.

- Safer Vehicles: Develop proposals to update consumer information on vehicle safety performance through the New Car Assessment Program (NCAP or Program), particularly to emphasize safety features that protect people both inside and outside of the vehicle.

- Safer Speeds: Develop and improve the information available for setting speed limits through Proven Safety Countermeasures and the Manual of Uniform Traffic Control Devices, providing a range of methodologies depending on the context of the roadway.

- Safer Speeds: Revise FHWA guidance and regulations to account for the safety of all users by encouraging the setting of context-appropriate speed limits and creating roadways that help to “self-enforce” speed limits.

- Post-Crash Care: Expand the use of and support for the National Emergency Medical Services Information System — the national database that is used to store EMS data from the U.S. States and Territories — by funding applied research and data quality improvements.

Some additional “slices” to prevent traffic deaths include:

- Personal Responsibility: Not speeding and not driving while distracted, intoxicated, or drowsy to reduce both the risk and severity of a crash.

- Urban Roadway Design: Ending the application of “forgiving” design standards in urban areas and prioritizing narrow lanes, tight curves, and frequent intersections to reduce driving speed thus reduce risk and severity of a crash.

- Urban Roadway Design: Reducing posted speed limits and implementing traffic calming measures in urban areas to reduce speeding thus reduce risk and severity of a crash.

- Urban Roadway Design: Improving sidewalks, bike lanes, and public transit to improve safety of multimodal feasibility to reduce vehicle miles traveled to reduce the risk of a crash.

- Urban Roadway Design: Targeting safety measures in crash hot spot areas to prevent additional crashes.

- Urban Design: Prioritizing compact, mixed-use land use to reduce the distance between destinations to reduce vehicle miles traveled to reduce the risk of a crash.

- Vehicle Safety Tests: Considering child occupant protection and pedestrian head and leg impact protection in vehicle safety tests to identify risks related to vehicle design and size.

- Vehicle Design: Eliminating vehicle blind spots to prevent crashes.

- Vehicle Design: Lowering the height of and eliminating blunt bumpers/hoods to reduce damage in a crash.

- Vehicle Design: Reducing the size and weight of vehicles to reduce kinetic energy thus damage in a crash.

- Vehicle Technology: Safety technologies that sense people outside the vehicle to prevent crashes.

- Driving Regulation: Ignition interlock systems target individuals that were charged with drunk driving and temporarily restricts their ability to drive their vehicle unless able to prove through the device that their blood alcohol concentration is below that allowed by the monitoring authority.

- Data Collection: Collecting better data on roadway and land use attributes and vehicle size in traffic crash records systems.

- Data Collection: The National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS) database could provide more helpful data in that it collects State and Territorial EMS fatality and injury data from 911 calls.

Some may argue against ignition interlock laws, for example, because they don’t do anything to prevent first-time offenders from driving drunk or to prevent sober drivers from speeding and driving recklessly.

This is why ignition interlock systems should be layered with other public health prevention strategies/slices to cover holes.

For example, two of the National Roadway Safety Strategy objectives are to “design roadway environments to mitigate human mistakes,” and “promote safer speeds in all roadway environments through a combination of thoughtful, context-appropriate roadway design, targeted education and outreach campaigns, and enforcement.”

The Swiss Cheese Model of Risk Reduction provides a helpful visual depiction of how a variety of strategies/slices are necessary to work together to prevent traffic deaths and firearm deaths.

But which strategies should be prioritized?

It is important to return to your theory of change logic model to ensure you understand and can explain how the proposed strategies will reduce violent child death. Again, this requires identification of and discussion about root causes, potential barriers, underlying assumptions, and necessary preconditions.

The following three frameworks will further guide discussions to develop and prioritize specific strategies/slices, with an emphasis on upstream population-level strategies that are equitable and not intrusive.

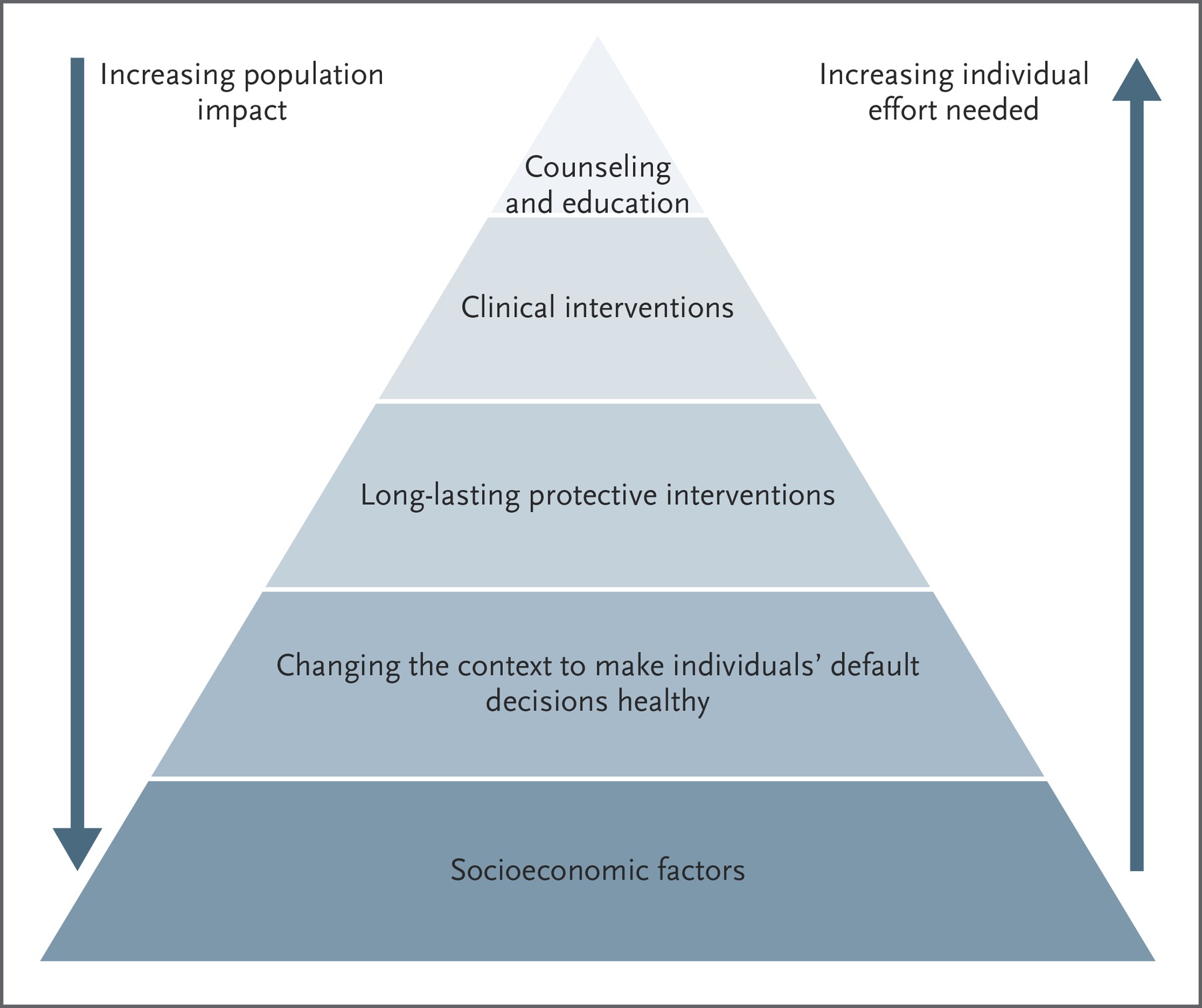

Framework 3 for Preventing Violent Child Deaths: Three-Levels of Prevention Strategies

When considering strategies/slices to layer prevent violent child death, there are three levels of prevention strategies to consider: primary, secondary, and tertiary.

Primary prevention strategies emphasize systemic change to improve outcomes for entire populations by preventing risk factors and increasing protective factors.

Secondary prevention strategies detect risk factors and target interventions to prevent the extent and severity of negative outcomes.

Tertiary prevention strategies manage negative outcomes after they have occurred. These strategies often include medical treatment and/or support programs for victims of traffic violence or gun violence as well as punitive action for perpetrators of traffic violence or gun violence.

Primary prevention strategies often have the greatest population impact, followed by secondary prevention strategies. Tertiary prevention strategies often have the least impact – yet require the most individual effort.

Primary Prevention Strategies to Prevent Violent Child Deaths

Primary prevention strategies emphasize systemic change to improve outcomes for entire populations by preventing risk factors and increasing protective factors.

Primary prevention strategies often include laws and policy changes that impact entire populations, such as reduced speed limits in school zones, requiring air bags in vehicles, banning handgun sales to individuals younger than 21, and expanding access to social, emotional, and mental health services and supports.

These strategies also include broad efforts to reduce poverty, address structural racism, and improve access to quality housing, education, transportation, job training and social services.

Specific examples of primary prevention strategies to prevent traffic deaths include:

- Urban Roadway Design: Ending the application of “forgiving” design standards in urban areas and prioritize narrow lanes, tight curves, and frequent intersections to reduce driving speed thus reduce risk and severity of a crash.

- Urban Roadway Design: Improving sidewalks, bike lanes, and public transit to improve safety of multimodal feasibility to reduce vehicle miles traveled to reduce the risk of a crash.

- Vehicle Design: Lowering the height of and eliminating blunt bumpers/hoods to reduce damage in a crash.

- Vehicle Design: Reducing the size and weight of vehicles to reduce kinetic energy thus damage in a crash.

Specific examples of primary prevention strategies to prevent gun deaths include:

- Stop Perpetuating Segregation: Outlawing discrimination based on income, to include ending exclusionary zoning, such as single-family zoning, and eliminating lot size restrictions in urban areas, particularly near mass-transit hubs, to stop trapping low-income families in disadvantaged and low-opportunity neighborhoods.

- Prevent, Detect, and Mitigate Toxic Stress: Adopting strategies in healthcare, social services, early childhood, education, and justice to prevent, detect, and mitigate toxic stress.

- Firearm Sales Regulation: Banning assault rifles and high-capacity magazines.

- Criminal Laws: Repealing shoot first/stand your ground laws.

Data collection could also be considered a primary prevention strategy.

Thus, we need to increase investment in the study of risk patterns and preventive measures to prevent traffic deaths and firearm deaths, to include socioeconomic, community, and policy factors.

A theory of change logic model can support efforts to make these distinctions and identify the relationship between risk factors for violent child death and intended strategy effects.

Again, there is an important distinction between downstream and upstream primary prevention strategies.

Downstream primary prevention strategies address the symptoms of the problem while upstream primary prevention strategies address the root causes of the problem.

Again, developing a causal model along with a theory of change logic model can help you identify where your proposed strategies fit into the vast sphere of numerous other factors that impact child firearm death and child traffic death.

When considering primary prevention strategies to reduce violent child death, it is important to consider upstream strategies to address the root causes of the risk factors.

Inclusionary zoning, for example, is a policy that requires housing developers to designate a small share of newly constructed housing units to be affordable for low-income households.

This policy is often justified as a solution to segregation and the lack of affordable housing in high-opportunity neighborhoods, both of which are risk factors for gun violence.

Although this policy could be considered a primary prevention solution to increase the affordable housing stock in high-opportunity neighborhoods, this policy does nothing about the existing exclusionary zoning practices, such as single-family zoning, that perpetuate segregation and concentrate poverty in low-opportunity neighborhoods.

As long as exclusionary zoning persists, cities will continuously have to justify, incentivize, and fund the piecemealing of inclusionary zoning and various other incomplete policies to compensate for the sustained harms of one antiquated policy.

Thus, inclusionary zoning is a downstream strategy and eliminating single-family zoning is an upstream strategy.

While it is important to layer both downstream and upstream primary prevention strategies, it is particularly important to develop and advocate for upstream strategies.

Secondary Prevention Strategies to Prevent Violent Child Deaths

Secondary prevention strategies detect risk factors and target interventions to prevent the extent and severity of negative outcomes.

Secondary prevention strategies often include tailored interventions, such as targeting traffic safety measures in crash hot spot areas to prevent additional crashes, revoking an individual’s driver’s license after being charged with drunk driving, targeting counseling programs for all victims of violence to prevent recurring violence, and providing gun lockboxes to individuals with children to encourage safe firearm storage practices.

Specific examples of secondary prevention strategies to prevent traffic deaths include:

- Urban Roadway Design: Safety measures in traffic crash hot spot areas which target funding and intervention to roads and intersections with higher rates of traffic crashes so that all people who live near and drive on those roads benefit.

- Driving Regulation: Ignition interlock systems target individuals that were charged with drunk driving and temporarily restricts their ability to drive their vehicle unless able to prove through the device that their blood alcohol concentration is below that allowed by the monitoring authority.

Specific examples of secondary prevention strategies to prevent gun deaths include:

- Firearm Sales Regulation: Prohibiting the sale of firearms to high-risk groups, such as domestic violence offenders, persons convicted of violent misdemeanor crimes, and individuals with mental illness who are risk to themselves or others to reduce threats.

- Firearm Regulation: Federal extreme risk protection orders to temporarily restricts access to firearms for those identified by law enforcement, family, or physicians and deemed by civil courts as being high-risk for violence.

- Gun Dealers: Reforming or shutting down the “bad apple” licensed gun dealers, to include preventing the sale of guns to straw purchasers or gun traffickers, to reduce the supply of illegal guns.

- Gun Kits: Requiring commercial manufacturers of unserialized gun kits to become licensed and include serial numbers of the kits frame or receiver and requiring commercial sellers of these kits to become federally licensed and run background checks prior to a sale.

Again, it is important to return to your theory of change logic model to ensure you understand and can explain how the proposed prevention strategies will reduce violent child death, to include consideration for barriers, assumptions, and preconditions.

However, many Americans are concerned about primary and secondary prevention strategies that are intrusive and may eliminate or restrict their choices, such as ignition interlock systems and bans on high-capacity magazines.

One approach to considering the least intrusive primary and secondary prevention strategies to layer is the Ladder of Intervention.

Framework 4 for Preventing Violent Child Deaths: The Ladder of Intervention

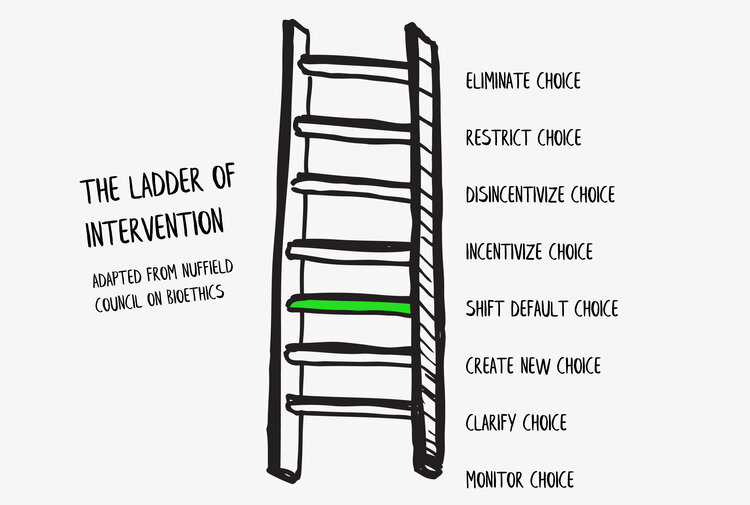

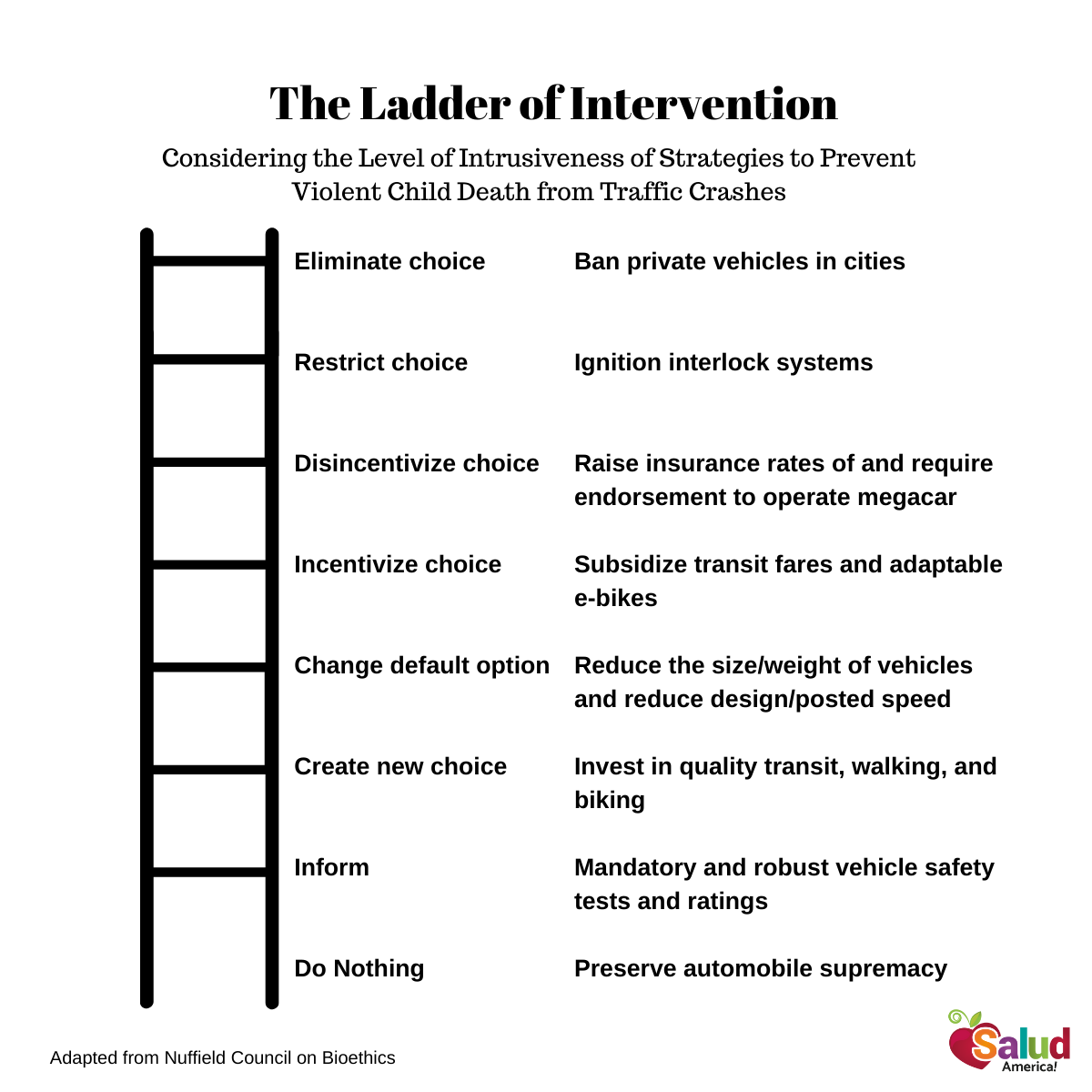

When considering primary prevention strategies to prevent violent child death, the Ladder of Intervention can facilitate conversation about the level of intrusiveness of each strategy.

The Ladder of Intervention provides a framework to consider how intrusive strategies are and if they negatively interfere with freedom.

The bottom of the ladder represents inaction, or limited government.

Government action increases the higher you go up the ladder, and strategies high on the ladder that restrict or eliminate choice interfere with individual rights, warranting proper justifications for the strategy.

After all, individual rights and limited government are hallmarks of the American Dream.

However, the concept of limited government has been muddied.

“The environment in which the citizen is free from all influence is a fiction,” according to the philosophers who developed the “Balanced Intervention Ladder” as a framework to understand the relationship between autonomy and public health—government—action.

The argument that there is no place for government regulation is flawed because we have come to rely on government regulation for many aspects of safety and general welfare.

Here are a few regulations specific to vehicle manufacturing and operation:

- Since 1992, drivers of commercial vehicles weighing more than 26,001 pounds or transporting more than 16 passengers must complete a knowledge and skills test and obtain a Commercial Driver’s License, for which there are various additional required endorsements for special types of commercial vehicles, such as double/triple trailers and hazardous materials.

- Many states have laws requiring vehicle owners replace their tires if tread is too low.

- All states have posted maximum speed limit laws.

- 34 states and Washington D.C. have enacted ignition interlock laws requiring all drunk driver offenders to install an ignition interlock on their vehicle, in which the driver must test their blood alcohol concentration before they can start their vehicle.

Here a few regulations specific to weapon manufacturing and operation:

- Federal law prohibits the transfer or possession a machine gun

- Federal law prohibits a person from assembling a non-sporting semiautomatic rifle or shotgun from 10 or more imported parts

- Federal law prohibits a person from assembling a firearm that cannot be detected by metal detectors or X-ray machines

Of course, past regulation alone does not justify future regulation.

Rather, a clear understanding and explanation about how the proposed strategy will reduce violent child death is necessary before discussions about the potential level of intrusiveness.

Thus, the Ladder of Intervention can contribute to the development of a theory of change logic model by providing a lens by which to examine the level of intrusiveness of existing and proposed strategies to prevent violent child deaths.

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) recommends “constitutionally-appropriate restrictions on the manufacture and sale, for civilian use, of large-capacity magazines and firearms,” recognizing the importance of addressing the relevance and limitations regarding the constitution.

Two examples of existing strategies that restrict choice are ignition interlock systems and extreme risk protection orders.

Ignition interlock systems temporarily restricts the choice to drive drunk for the few individuals that were charged with drunk driver by requiring them to prove through the device that their blood alcohol concentration is below that allowed by the monitoring authority.

In short, using ignition interlock laws as a strategy to reduce traffic violence does restrict choice, but only for those charged with drunk driving who are choosing at that moment to drive drunk. To maintain transparency and garner public support when advocating for strategies, it is important to be clear about intrusiveness.

Extreme risk protection orders temporarily restrict the choice to access a firearm for the few individuals that were identified by law enforcement, family, or physicians as being high-risk for perpetrating gun violence, often due to explicit threats of gun violence. In short, using extreme risk protection laws as a strategy to reduce gun violence does restrict choice, but only for those at high risk of gun violence, such as those who have made explicit threats, who are choosing to access a firearm.

It is important to note that the restriction of choice through these two laws is subject to a process that implements various checks and balances of power to prevent unintended and unnecessary interference.

“A 2016 ballot measure in Washington state on whether courts should be authorized to issue extreme risk protection orders—argued that extreme risk protection orders included ‘careful protections for due process and standards for evidence,’” according to Ballotpedia.

Anyone who has filed—or knows someone who has filed—a domestic abuse charge, sexual assault charge, or protective order knows that the civil courts and criminal justice system do not move quickly and that alleged perpetrators are not always brought to justice.

Another example of a hypothetical strategy that restricts choice is limiting the size and weight of megacars.

Compare this to a hypothetical strategy that uses a disincentive by requiring owners of megacars to pay more for automobile insurance or to obtain a special endorsement to operate a megacar.

An example of an existing strategy that changes the default option is requiring automakers to include seat belts in every car they build.

In 1996, Congress required automakers to include seat belts in every car they built. By intervening and changing the default option, the government has helped save roughly 13,000 lives each year.

Thus, it should not be a stretch to consider that the government could intervene to change the default option for firearms and require gunmakers to include smart locks on every gun they build. Similarly, it should not be a stretch to consider that the government could intervene to change the default option for vehicles and restrict the size and weight of vehicles and height of bumpers.

The Ladder of Intervention can help you work through questions like:

- Is it intrusive to subject manufacturers, sellers, and owners of megacars and firearms to additional regulation?

- Is it intrusive to require vehicles manufacturers to conduct vehicle safety tests to determine the risk megacars pose to other road users, such as a people walking and biking?

- Is it intrusive to require gun manufacturers to install some form of identification technology to prevent use by unauthorized users?

It is through these types of strategies that our nation has successfully prevented many premature deaths from smoking, opioids, poisoning, drowning, fires, and traffic crashes.

More specifically, it is through these types of strategies that our nation has prevented these deaths without banning cigarettes, opioids, swimming pools, matches, or vehicles.

For example, thanks to vehicle safety regulations, annual vehicle inspections, and driver’s licensing requirements, you can drive without fear of getting impaled by your steering column; people around you driving on faulty tires, brakes, or gas tanks; people around you driving with poor vision; and truckers driving without rest.

Moreover, because the government requires that all drivers have auto insurance, you can drive knowing you will not have to pay for vehicle damage caused by someone else.

It would be foolish to own and operate a vehicle in public places without these regulations. However, given the growing size, weight and bumper height of SUVs and passenger trucks, existing regulations are not enough.

Preventing death and injury has come from translating research findings into effective policies, regulations, and interventions and then layering multiple upstream policies, regulations, and interventions, while prioritizing the least intrusive of those.

Discussions about the intrusiveness of prevention strategies supplement the development of a theory of change logical model and the overall public health approach to prevent violent child death.

In the spirit of identifying underlying assumptions per the theory of change logic model, it is important to point out that doing nothing (the bottom of the ladder) is not necessarily neutral.

An underlying assumption of the Ladder of Intervention is that inaction does not interfere with personal freedom, thus inaction does not require justification.

However, consider how driving is encouraged and subsidized.

“Law not only inflames a public health crisis but legitimizes it, ensuring the continuing dominance of the car,” wrote University of Iowa law professor Greg Shill in a research paper about how traffic law, land use regulation, environmental law, tax, and tort have subsidized driving resulting automobile supremacy.

Thus, doing nothing preserves automobile supremacy, thus stakeholders should be required to justify their inaction.

Additionally, regarding doing nothing, consider shoot first/stand your ground laws which allow a person to kill another person even when they could have safely retreated.

Shoot first/stand your ground laws violate the rights of alleged criminals to due process through the criminal justice system because they allow a person to determine and execute on the spot the punishment of death by shooting by their own hand.

Violating the rights of due process is a very American example of the definition of interference with personal freedom.

States who do nothing to repeal these laws are allowing intrusive—and dangerous—laws to persist.

Thus, they should be required to justify their inaction.

Regardless of level of intrusiveness, inaction should require a similar level of justification as action.

Inaction is an application of values, even if those values are unspoken, and requiring justification will shed light on those values.

Additionally, inaction can perpetuate existing risk factors by leaving the root causes unchanged.

This reinforces the importance of identifying the root causes of the problem—as explained through the second step in the public health approach in this series, as well as explained through the theory of change logic model and causal model of factors previously in this post.

For example, in addition to the many problems with segregation, because segregation is a risk factor for gun violence, community leaders should be required to justify maintaining exclusionary zoning similar to how they are required justify new strategies, such as inclusionary zoning and land banks.

Thus, inaction should be addressed in your theory of change logical model, particularly regarding inaction on existing policies that create and contribute to risk factors for violent child death.

Upon development of a theory of change logical model and development of upstream prevention strategies through the application of the Swiss Cheese Model of Risk Reduction, Three-Levels of Prevention Strategies, and Ladder of Intervention frameworks, the fifth and final framework focuses on equitable strategies.

Framework 5 for Preventing Violent Child Deaths: Racial Equity Assessment Tools

As local, state, and federal leaders develop strategies to prevent violent child deaths, they need to ensure those strategies will not perpetuate institutional racism or existing inequities.

Thus, leaders need to assess both internal practices and laws and policies.

Fortunately, several racial equity tools exist to help organizations assess internal practices, such as recruiting, hiring, and promoting, and help decision-makers assess policies, programs, and projects, such as local ordinances, strategic plans, and annual budgets.

More specifically, many racial equity tools help identify biased practices and policies that continue to disenfranchise communities.

Below are a few examples of tools that should be applied simultaneously with the four frameworks mentioned above. Because, as mentioned in the previous article in this series, the discriminatory practices that created unequal neighborhoods marked by white advantage and racial disadvantage are risk factors for violent child deaths.

“Too often, policies and programs are developed and implemented without thoughtful consideration of racial equity,” according to The Government Alliance on Race and Equity (GARE). “When racial equity is not explicitly brought into operations and decision-making, racial inequities are likely to be perpetuated. Racial equity tools provide a structure for institutionalizing the consideration of racial equity.”

Many of the tools recommend first understanding and acknowledging the historical context for the legacy of racial inequity. This should include geospatial mapping discriminatory laws and policies such as zoning, redlining, urban renewal, public housing, and federal highways along with social, economic, and health outcomes such as educational attainment, income, access to healthy food, infant mortality, asthma, diabetes, traffic deaths, gun deaths, and premature mortality.

One tool from the National Association of Chronic Disease Directors explains it well:

“The intent of this tool is to shed light and NOT blame or shame. In order to fully understand how entrenched institutional racism is in our society, we have to know some of the dark truths in U.S. history. We must acknowledge the many points in history when foundations were laid that helped create and continue to perpetuate institutional racism. Once we understand the historical context we become better equipped to recognize opportunities to move toward institutional racial equity.”

To track progress, evaluate effectiveness, and justify continued support, many of the tools call for a data-driven approach with specific performance measures.

However, implicit bias, moral disengagement, and hidden or unspoken assumptions, justifications, and decisions can threaten equity work.

Class bias and individualistic beliefs about the causes of poverty, for example, can lead to morally disengaged people justifying the status quo by telling themselves that inequities are not a big deal or by reducing their identification with disadvantaged populations, saying they did something to deserve the inequities they face, according to a research review from Salud America!

An example of an assumption that is embedded in urban planning is that single-family zoning is necessary to protect the public health, safety, and welfare of the families who can afford to live there from the ills brought about by the families who live in multi-family units. Despite nearly 100 years of implementation, there is zero empirical evidence to suggest that duplexes, triplexes, or quadplexes harm public health, safety, or welfare.

Again, a theory of change logic model can be helpful in identifying thus combatting some of these hidden assumptions.

Below are a handful of resources to understand and strengthen racial equity tools for governments to address systemic racism in government operations, such as strategic planning, decision-making, policies, and practices.

Similar to evaluating policies for budget impact, many equity advocates have urged elected officials to also evaluate policies for equity impacts, known as equity impact assessment.

Gauging the Impacts of Policy Proposals on Racial Equity. Brookings Metro and the Institute on Race, Power and Political Economy at The New School are exploring how racial equity impact assessment are being embedded into government consideration of policy proposals.

They released a preliminary research review explaining the evolution of equity analysis in public policy, the four functions of equity assessment tools, and recurring challenges for racial equity impact assessment.

Scoring Federal Legislation for Equity. The Urban Institute and PolicyLink teamed up to develop a report to help federal leaders understand and assess whether every policy advances or impedes equity.

Scoring Federal Legislation for Equity: Definition, Framework, and Potential Application explains how scoring will help advance equity and provides a framework for equity scoring based on budget scoring experience.

Extending the current practice of federal budget scoring to include equity scoring would provide “Congress information on how legislative proposals would advance or harm racial equity [which] would allow more informed debate and more deliberate decision-making,” the report states.

The report also identifies common themes in the current state and local landscape of equity assessments in the legislative process.

GARE’s Racial Equity Tools. The Government Alliance on Race and Equity (GARE) has developed multiple resources to support the intentional consideration of systemic racism into government operations.

One of their primary resources is their Racial Equity Toolkit: An Opportunity to Operationalize Equity.

The Racial Equity Tool is a simple set of six questions:

- Proposal: What is the policy, program, practice or budget decision under consideration? What are the desired results and outcomes?

- Data: What’s the data? What does the data tell us?

- Community engagement: How have communities been engaged? Are there opportunities to expand engagement?

- Analysis and strategies: Who will benefit from or be burdened by your proposal? What are your strategies for advancing racial equity or mitigating unintended consequences?

- Implementation: What is your plan for implementation?

- Accountability and communication: How will you ensure accountability, communicate, and evaluate results?

Below is an example of how the first three steps in GARE’s racial equity toolkit can be applied to a common local ordinance, single-family zoning:

- What is the policy, program, practice or budget revision under consideration, and what are the desired results and outcomes? Single-family zoning. The desired results and outcomes of single-family zoning in [YOUR CITY], are [GOALS AND JUSTIFICATION IN CITY ORDINANCE ADOPTING SINGLE-FAMILY ZONING AS WELL AS JUSTIFICATIONS FOR APPROVING/REJECTING CHANGES TO THE ZONING CODE].

- What does the data tell us? [PERCENT] of land zoned for residential use in [YOUR CITY] is zoned single-family. Of residential land zoned single-family, [PERCENT] of the population is white compared to [YOUR CITY] which is [PERCENT] white. Of residential land not zoned single-family, [PERCENT] of the population is Latino or black compared to [YOUR CITY] which is [PERCENT] Latino or black. The average income of residents living in areas zoned single-family is [AVERAGE INCOME OF RESIDENTS LIVING IN AREAS ZONED SINGLE FAMILY], compared to the average income of residents living in areas not zoned single family, [AVERAGE INCOME OF RESIDENTS LIVING IN AREAS ZONED SINGLE FAMILY]. [ALSO LOOK FOR DATA ON EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT OF HOUSEHOLDS IN AREAS ZONED SINGLE-FAMILY COMPARED TO THE CITY; RATE OF FIREARM DEATHS AND INJURIES IN AREAS ZONED SINGLE-FAMILY COMPARED TO THE CITY; AND RATE OF TRAFFIC DEATHS AND INJURIES IN AREAS ZONED SINGLE-FAMILY COMPARED TO THE CITY.]

- How have communities been engaged and are there opportunities to expand engagement? In [YOUR CITY], communities engaged in the initial passing of the ordinance were [EXPLAIN MAKEUP ACROSS RACIAL/ETHNIC, GENDER, EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT, AND INCOME GROUPS OF THOSE INVOLVED IN THE INITIAL PASSING OF THE ORDINANCE]. Communities engaged in recent changes/amendments to the zoning code have been [EXPLAIN MAKEUP ACROSS RACIAL/ETHNIC, GENDER, EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT, AND INCOME GROUPS OF THOSE RECENTLY ENGAGED IN CHANGES/AMMENDMENTS].

The general idea is, beyond scoring policies for budget impacts, we should also score policies for equity impacts.

You can apply this framework to address risk factors for and ensure equitable strategies to prevent violent child deaths from gun violence and traffic crashes.

One of GARE’s other resources, Racial Equity: Getting to Results, emphasizes the need for Results-Based Accountability that incorporates a racial equity lens, where leaders start with the desired results and work backward to the means.

These questions will look somewhat familiar to some of probing questions used to think through a theory of change logic model. Even if you addressed these thoroughly, equity frameworks can provide a sort of stop gap to ensure any shortcomings or oversights don’t sneak through.

This framework begins with seven primary questions about the whole population:

- What are the desired results?

- What would the result look like?

- What are the community indicators that would measure the desired result?

- What do the data tell us?

- Who are your partners?

- What works to change the data trends towards racial equity?

- What actions should you start with?

Upon identifying a set of actions, this framework provides seven questions to guide action refinement and the development of performance measures:

- Who do you serve?

- What is an action’s intended impact?

- What is the quality of the action?

- What is the story behind the data?

- Who are the partners with a role to play?

- What works to have greater impact?

- What are the next steps?

You can apply this framework to develop and push for equitable strategies to prevent violent child deaths from gun violence and traffic crashes.

PolicyLink’s Racial Equity Tools. In partnership with the University of Southern California’s Program for Environmental and Regional Equity (PERE), PolicyLink developed the National Equity Atlas as a tool with disaggregated data across 301 geographies to measure, track, and make the case for inclusive growth.

They also developed the Racial Equity Index which provides a snapshot of how well a given place is performing on racial equity compared to its peers based on nine equity indicators.

PolicyLink also developed a toolkit to help promote justice in policing, which is particularly relevant for developing equitable law enforcement-related strategies to prevent firearm violence and traffic deaths.

However, some of these racial equity resources from GARE and PolicyLink do not consider the root causes of inequities. They also don’t make the distinction between upstream and downstream strategies and don’t recommend a theory of change logic model to understand and explain how the proposed strategies will produce expected outcomes.

PolicyLink’s housing and anti-displacement tools, for example, don’t have a recommendation to eliminate exclusionary zoning. The transportation-related indicator they use in their Racial Equity Index focuses on travel time to work without regard for traffic deaths and injuries or transportation cost burden.

While these tools will support efforts to ensure strategies to prevent violent child deaths are equitable, they still need to be guided by a theory of logic model that considers hidden justifications, assumptions, and policies.

In a 2021 report, the Institute for Health Justice and Equity provides a brief overview of the foundational components of the racial equity tools from GARE and PolicyLink and catalogues how jurisdictions are using these tools to address systemic racism and the social determinants of health in their communities.

It is also important to consider internal practices and organizational capacity to utilize these tools to address violent child death.

Organizational Self-Assessment. State Health Department Organizational Self-Assessment for Achieving Health Equity was developed by the National Association of Chronic Disease Directors to help public health leaders identify the skills, organization practices, and infrastructure necessary to achieve health equity.

The goal is to assess the overall ability of a local or state health department to impact the factors that influence community health and well-being, such as institutionalized racism and social, economic, and environmental conditions.

The assessment involves a staff survey, external partner survey, staff focus group, management interviews, management focus groups, and an internal document review, all to determine staff, partner, and management perspectives of the department’s capacity to address social, economic and environmental determinants of health.

To connect the findings from the various elements of the assessment, the Self-Assessment includes a matrix of nine organizational characteristics and nine workforce competencies and maps the questions from each of the surveys and focus group protocols across the characteristics and competencies.

For example, understands underlying causes of health inequities, institutional commitment to primary prevention, takes a system approach, and understands and uses data are workforce competencies that support key characteristics of a state health department to effectively address health inequities, and the document lists the survey and focus groups questions that align with each of these competencies.

“The Self-Assessment will disclose a comprehensive set of information from a variety of sources about the strengths and areas for improvement related to skills and capacities supporting institutional capacity to achieve health equity,” according to the Self-Assessment.

The assessment could be adapted for public health leaders focus on addressing violent child death.

For example, some of the survey and focus group questions could be adapted to determine the perspectives of the department’s capacity to specifically address the factors that influence violent child deaths from firearm violence and traffic crashes.

A question from the staff survey could be modified from “Please list what you think are the most important root causes of health inequities among the populations of the state” to “Please list what you think are the most important root causes of violent child death from gun violence and traffic crashes in the state.”

Similarly, a question from the management focus group protocol could be modified from “What specific strategies and objectives has the department undertaken to address the social, economic, and environmental conditions that influence health” to “What specific strategies and objectives has the department undertaken to address the social, economic, and environmental conditions that influence violent child death from gun violence and traffic crashes.”

Moreover, the assessment could be adapted for transportation leaders to focus on addressing traffic crashes.

For example, the matrix of organizational characteristics and workforce competences could be adapted with an emphasis on the characteristics of local and state transportation departments that can effectively address traffic crashes as well as the skills and abilities needed by local and state transportation departments to effectively address traffic crashes.

If adapted for transportation planning departments, the self-assessment could disclose a comprehensive set of information from a variety of sources about the strengths and areas for improvement related to skills and capacities supporting institutional capacity to prevent traffic crashes.

Washington D.C.’s Racial Equity Impact Assessment. In January 2021, Washington, D.C., City Council voted to require a Racial Equity Impact Assessment (REIA) for almost every piece of legislation that the Council proposes using this racial equity tool.

Since October 2021, D.C.’s Council Office of Racial Equity has completed 97 Racial Equity Impact Assessments requested by various Council Committees, such as the Committee on Transportation and the Environment, the Committee on Judiciary and Public Safety, the Committee on Health, and the Committee on Government Operations and Facilities.

For example, in October 2022, D.C.’s Council Office of Racial Equity prepared a Racial Equity Impact Assessment for DC’s Ignition Interlock System Program, which was being expanded to people who are arrested in another jurisdiction.

As mentioned previously, ignition interlock systems target individuals that were charged with driving under the influence of alcohol and temporarily restricts their ability to drive their vehicle unless able to prove through the device that their blood alcohol concentration is below that allowed by the monitoring authority. Also, as explained in the previous article in this series, ignition interlock systems are protective factors against traffic deaths and injuries.

Prepared for the Committee on Transportation and the Environment, D.C.’s Council Office of Racial Equity concluded that their Ignition Interlock System Program “will likely improve health and safety outcomes for Black and Latinx residents.”

This is because in D.C,, “four of five neighborhoods with the most [traffic] deaths over the past eight years are home to majority-Black residents and at least 58 percent of victims citywide were Black,” according to the Racial Equity Impact Assessment.

However, the assessment also concluded that “the bill does not specify whether data will be collected and published on the participation and outcomes of the program” and that “racial inequities in DUI enforcement may limit the positive impacts of the bill.”

“While behavior is consistent across racial groups, Black people are more likely to be impacted by the criminal legal system,” to include more likely to be arrested for cannabis possession despite similar cannabis us as white residents and more likely to be detained even when they aren’t violating the law compared to white residents, according to the Racial Equity Impact Assessment.

As mentioned previously, the toolkit from PolicyLink will help promote justice in policing.

Thus, although ignition interlock systems are protective factors and this strategy should be layered with other primary prevention strategies, as explained above, there are important equity considerations during implementation to eliminate racial inequities in enforcement.

As of November 9, 2022, D.C.’s Council Office of Racial Equity was in the process of conducting a Racial Equity Impact Assessment for the bill “Omnibus Firearm and Ghost Gun Clarification Amendment Act of 2022” for the Committee on Judiciary and Public Safety.

The purpose of the bill “is to amend the Firearms Control Regulations Act of 1975 to clarify requirements involving ghost guns, permit the possession of properly serialized self-manufactured firearms that are not otherwise prohibited, regulate carrying of firearms by off-duty law enforcement officers, and expand the prohibition on carrying a pistol while impaired. The bill further amends An Act To control the possession, sale, transfer and use of pistols and other dangerous weapons in the District of Columbia, to provide penalties, to prescribe rules of evidence, and for other purposes, to clarify restrictions on the lawful transportation of firearms, apply the same rules to stay-away orders that apply to orders prohibiting harassment, assault, threats, and stalking, and authorize and limit the carrying of pistols by off-duty law enforcement officers, other United States officers while on duty, manufacturers, and those transporting firearms for limited purposes.”

Also in 2021, the Council voted to require District agencies, such as the Zoning Commission, to evaluate their implementation of the Comprehensive Plan’s policies and actions through a “racial equity lens.”

The Zoning Commission has since released its initial racial equity analysis tool, which includes themes and questions the Commission will use in its evaluation of zoning actions.

Although recognition is growing that systemic racism is real and pervasive, shifts in attitudes do not automatically lead to necessary policy changes.

Tools like those mentioned above to guide equity considerations in discussions about strategies to prevent violent child deaths are important to ensure strategies will not exacerbate inequities in firearm deaths and traffic deaths.

Moreover, although recognition is growing that systemic change is needed to prevent violent child death, shifts in narratives do not automatically lead to necessary policy changes.

Thus, there is a need to explore how beliefs and attitudes, such as classism, implicit bias, system justification, moral disengagement, and belief in meritocracy, influence decisionmakers’ narratives thus willingness to support upstream strategies to prevent violent child death.

While understanding how decisionmakers’ beliefs and attitudes influence their narratives thus their support/opposition for prevention strategies is important to make the case for and frame those strategies, those psychological issues are beyond the scope of this series.

“By accurately understanding and assessing the effects of legislative outcomes and connecting these analyses to the legislative process, the data that equity scoring provides can give federal legislators the tools to prioritize equitable policies and help racial equity movement leaders, the media, and the public change public and private narratives about legislation,” according to Scoring Federal Legislation for Equity.

We Need a Comprehensive and Multi-Layered Public Health Approach

Overall, preventing violent child deaths from traffic crashes and firearms requires a comprehensive and multi-layered public health approach to:

- Define and monitor the problem

- Identify risk and protective factors

- Develop prevention strategies

- Ensure adoption of strategies.

Read the first two posts in the series about defining and monitoring the problem and identifying risk and protective factors.

To develop prevention strategies, we need to utilize the above frameworks, particularly the theory of change logic model.

You can use different perspectives from these five frameworks to justify the need for action and urge local, state, and federal leaders to take action to prevent violent child deaths and injuries in America.

Stay tuned for the fourth and final post in this series about ensuring the adoption of strategies, to be released Dec. 15, 2022!

By The Numbers

27

percent

of Latinos rely on public transit (compared to 14% of whites).