Share On Social!

Toxic stress is brought about by repeated stressful and traumatic experiences with no supportive relationships. This is causing huge mental and physical health problems for people across the nation, including Latinos and other people of color.

Dr. Nadine Burke Harris even calls toxic stress a public health crisis.

This is why she authored the Roadmap for Resilience: The California Surgeon General’s Report on Adverse Childhood Experiences, Toxic Stress, and Health.

“We now understand that a key mechanism by which ACEs [adverse childhood experiences, such as divorce, abuse, poverty, etc.] lead to increased health risks is through a health condition called the toxic stress response,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states.

Salud America! is exploring this issue as part of its 11-part series on toxic stress.

What is Stress? What is Toxic Stress?

Stress is defined as a “real or interpreted threat to the physiological or psychological integrity of an individual which results in physiological and/or behavioral responses,” according to the Encyclopedia of Stress.

Stressors can vary:

- learning something new for school or work

- hosting a family event

- caring for a sick family member

- witnessing or being a victim of violence

- dealing with discrimination

- enduring a physical injury

Some of these stressors may “seem” worse than the others.

But no matter how stressful a certain experience may seem, the body reacts to stress through a complex process of biological set points and physiological responses.

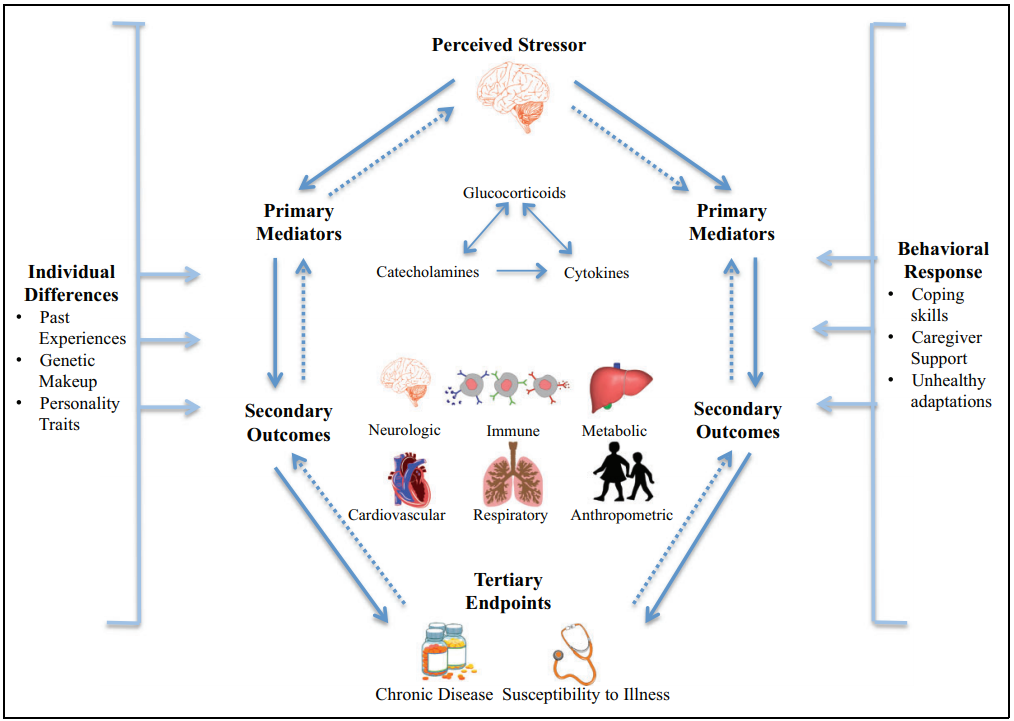

“Most of the biological reactions that facilitate these normal responses are driven by two main systems: the sympatho-adreno-medullary (SAM) axis, which makes the stress hormone adrenaline and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which makes the stress hormone cortisol,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states.

These changes happen so quickly that people aren’t aware of them.

These responses can affect the body in the following ways:

- Heart rate and blood pressure increase, channeling blood to the parts of the brain, organs, and muscles involved in the fight-flight-or-freeze response;

- Blood sugar and fats are released from temporary storage sites in the body; and

- Brain structures associated with threat and vigilance become more active, and the parts of the brain that facilitate impulse control, judgment, and executive function become less active.

The body is seeking homeostasis—and sometimes survival.

However, in addition to having protective effects, the stress response system can also have damaging effects─particularly if it doesn’t turn off.

“Too much stress or inefficient operation of the acute responses to stress can cause wear and tear and exacerbate disease processes,” according to the Encyclopedia of Stress.

There are three terms for the different ways the stress response system affects the body:

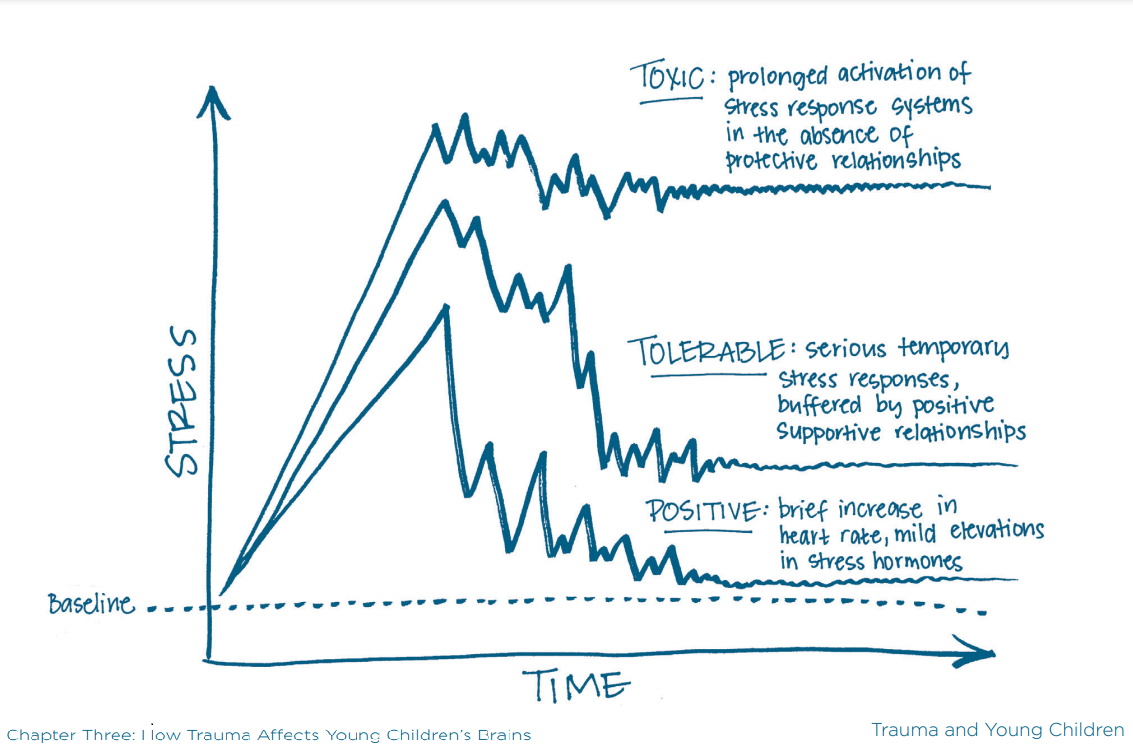

A positive stress response is brief increases in the heart rate and mild elevations in stress hormone levels. It is healthy and even life-saving when activated briefly in the short-term.

A tolerable stress response occurs when more serious or longer-lasting stressors occur and elevate stress hormones, but are buffered by supportive relationships. Supportive relationships help the stress response recover and regulate.

A toxic stress response occurs when the stress response is activated too frequently or intensely, which disrupts the development of the brain and other organ systems in childhood and alters important biological set points that govern functioning. Without the buffering protection of supportive relationships, a toxic stress response can lead to lifelong physical, mental, and behavioral health problems.

Important Distinction: A Stressful Event vs. the Stress Response System

There is an important distinction between how an individual thinks they react to and are affected by a stressful experience, versus how an individual’s stress response system affects many systems in the body regardless of a person’s perception of the experience.

The amygdala, hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and adrenal glands are already pumping stress hormones before an individual can decide what is stressful or not.

Even if a person perceives stress as slight, their stress response system can be activated.

“When activated too frequently or for too long, these systems can become dysregulated,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states.

A dysregulated stress response system leads to health and social problems across the lifespan.

Unfortunately, some adults brush off stressors in childhood as emotional issues that merely need to be forgotten. They may simultaneously share and dismiss stories of traumas in their childhood, claiming what happened did not have a lasting impact on their life or health.

Researchers do not support this idea.

Rather, researchers suggest that those people likely had a safe, stable adult to help buffer their stress response system from what might otherwise be damaging effects.

Supportive relationships mediate the extent to which stressful events have lasting effects.

In that case, they experienced a tolerable stress response.

“A nurturing parent or caregiver is a critically important resilience factor for children, turning potentially toxic stress into tolerable stress,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states.

If the adult who shared and dismissed stories of childhood trauma did not have supportive relationships, they likely experienced a toxic stress response which could have disrupted the development of their brain and other organ systems and put them at increased risk for disease and premature death throughout their life.

Whether an individual remembers or not and whether they are emotional or not, a dysregulated stress response system negatively impacts the brain, body, and behavior.

More about the Toxic Stress Response

Toxic stress response is a dysregulated biological stress response system and subsequent changes in other biological and physiological functions.

For example:

- SAM Axis (adrenaline): The sympatho-adreno-medullary (SAM) axis makes the stress hormone adrenaline. The SAM axis is normally active at baseline levels, but in response to stress, activity intensifies. The release of adrenaline rapidly and systemically prepares multiple organ systems to fight or to flee a threat by enhancing alertness, increasing heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration, funneling oxygenated blood and cellular fuel to the brain and skeletal muscles in the arms and legs, increasing immune activation, and temporarily pausing non-essential functions, including suppressing appetite and reproductive drive. When activated too frequently or for too long, the SAM axis can become dysregulated.

- HPA Axis (cortisol): The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis makes the stress hormone cortisol. The HPA axis is normally active at baseline levels, but in response to stress, activity intensifies. During stressful episodes, cortisol triggers the liver, fat cells, muscles, and the pancreas to increase blood sugar levels available to the brain and skeletal muscles, which boosts energy levels and readies the body to respond to a threat. Cortisol also increases blood pressure and cardiac output, while suppressing sleep, immune, reproductive, and growth functions. When activated too frequently or for too long, the HPA axis can become dysregulated.

Without supportive relationships to help the stress response recover and regulate, the frequent activation of the stress response system can result in irreversible changes in brain function. There can be permanent effects on behavior, as well as irreversible changes to neurological, endocrine, immune, metabolic, cardiovascular, and genetic regulatory mechanisms and functioning. Also, there can be permanent effects on health.

The toxic stress response is defined as “prolonged activation of the stress response systems that can disrupt the development of brain architecture and other organ systems, and increase the risk for stress-related disease and cognitive impairment, well into the adult years… For children, the result is the disruption of the development of brain architecture and other organ systems and an increase in lifelong risk for physical and mental health disorders,” according to the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine’s (NASEM) 2019 consensus report.

A positive or tolerable stress response is like a well-functioning thermostat that turns the stress response on and off to maintain homeostasis.

But a toxic stress response is like a broken thermostat that turns on too often and is unable to turn off.

“Chronic stress not only activates the stress response repeatedly, but gradually impairs feedback inhibition, compromising an organism’s capacity to recover back to baseline after a stressor,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states.

The biological impacts of toxic stress occur from the moment of conception, through birth, infancy, childhood, adolescence and adulthood.

They cause the most harm early in life, while the brain and body are still developing.

“When significant adversity is experienced during critical and sensitive periods of early life development, without adequate buffering protections of safe, stable, and nurturing relationships and environments, it can lead to prolonged activation of the biological stress response, and to long-term disruption of neuro-endocrine-immune-metabolic and genetic regulatory mechanisms,” the roadmap states.

Adversity during these critical development periods is also known as developmental trauma.

What is Developmental Trauma?

In 2005, Dr. Bessel A. van der Kolk constructed the diagnosis “Developmental Trauma Disorder” for the disruption to neurological, psychological, cognitive, and social functioning that occurs from trauma by caregivers during critical development periods in the early years of life.

“Chronic trauma interferes with neurobiological development and the capacity to integrate sensory, emotional and cognitive information into a cohesive whole,” according to van der Kolk.

These children are unable to regulate their internal and emotional states.

“Spaced out” and hyperaroused children learn to ignore either what they feel (their emotions), or what they perceive (their cognitions),” according to van der Kolk.

Distrusting themselves and unable to achieve a sense of control, these children learn to adjust to traumatizing environments, and “will organize their behavior around keeping the secret, deal with their helplessness with compliance or defiance, and acclimate in any way they can to entrapment in abusive or neglectful situations,” according to van der Kolk.

Distrusting themselves and unable to achieve a sense of control, these children learn to adjust to traumatizing environments, and “will organize their behavior around keeping the secret, deal with their helplessness with compliance or defiance, and acclimate in any way they can to entrapment in abusive or neglectful situations,” according to van der Kolk.

Without a supportive caregiver, these children experience the harms of a toxic stress response and may experience excessive anxiety and anger which can lead to dissociative states or self-defeating aggression.

“This results in problems with self-definition as reflected by a lack of a continuous sense of self, poorly modulated affect and impulse control, including aggression against self and others, and uncertainty about the reliability and predictability of others, expressed as distrust, suspiciousness, and problems with intimacy, resulting in social isolation,” according to van der Kolk.

Unfortunately, they are likely to be labeled as “oppositional,” “rebellious,” “unmotivated,” or “antisocial.”

“Developmental trauma sets the stage for unfocused responses to subsequent stress, leading to dramatic increases in the use of medical, correctional, social and mental health services,” according to van der Kolk.

What are the Risk Factors for Toxic Stress?

Risk factors for toxic stress are severe, intense, or prolonged stress, trauma, or adversity in childhood.

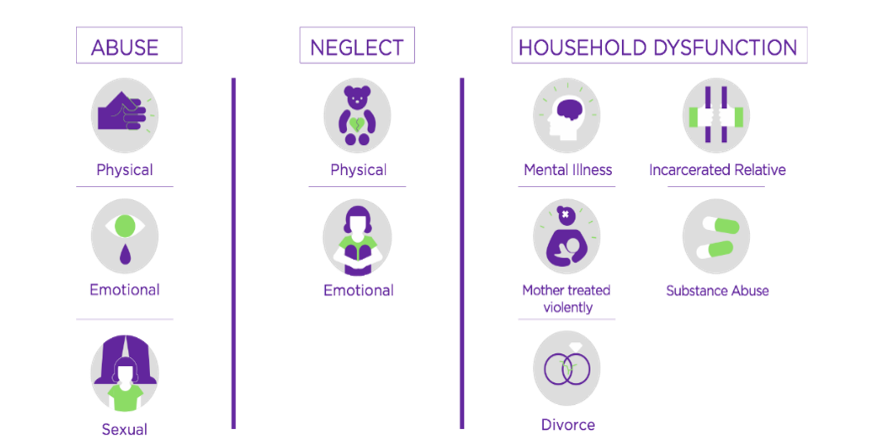

The term Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) specifically refers to the 10 categories of adversities experienced by age 18 or younger that were studied in the 1998 Centers for Disease Control/Kaiser Permanente study.

The 10 categories of adversities are:

- Physical child abuse

- Emotional child abuse

- Sexual child abuse

- Physical neglect

- Emotional neglect

- Household incarceration

- Household mental illness

- Household substance dependence

- Household parental separation or divorce

- Intimate partner violence

These were the most common adversities in the study population at the time, which was predominately white, middle class, college-educated.

Since the original ACEs study, additional adversities have been identified among more diverse populations, such as:

- racism

- sexism

- poverty

- food and housing insecurity

- interpersonal and community violence

- bullying

- death of a family member

- historical trauma

- growing up in care

- justice system involvement

“When caregivers are emotionally absent, inconsistent, frustrating, violent, intrusive, or neglectful, children are likely to become intolerably distressed and unlikely to develop a sense that the external environment is able to provide relief,” according to van der Kolk.

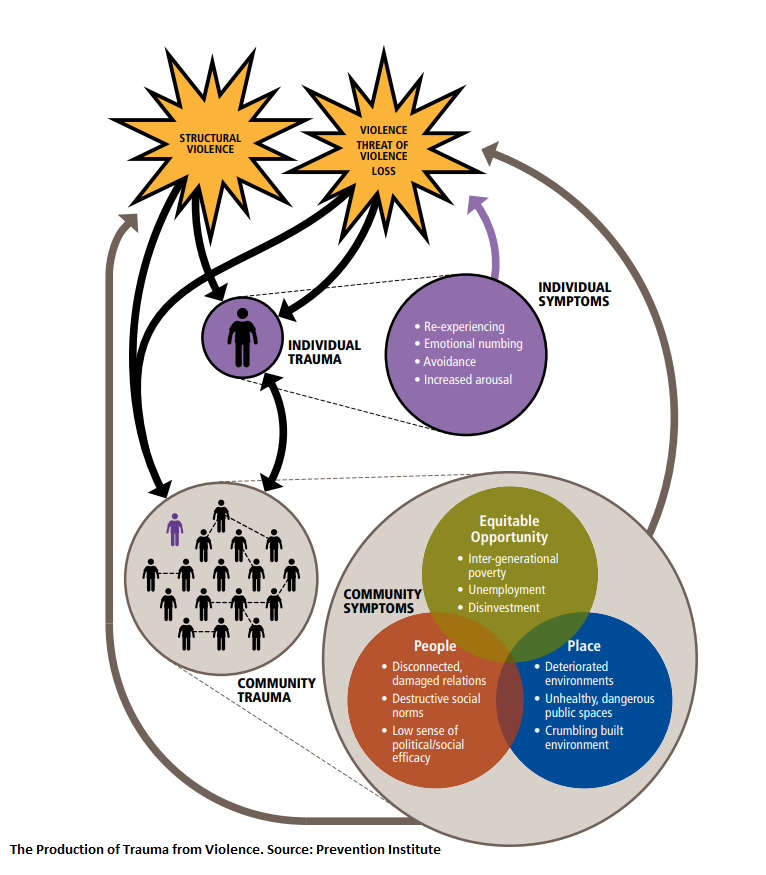

This results in toxic stress and developmental trauma, which can manifest at the community level.

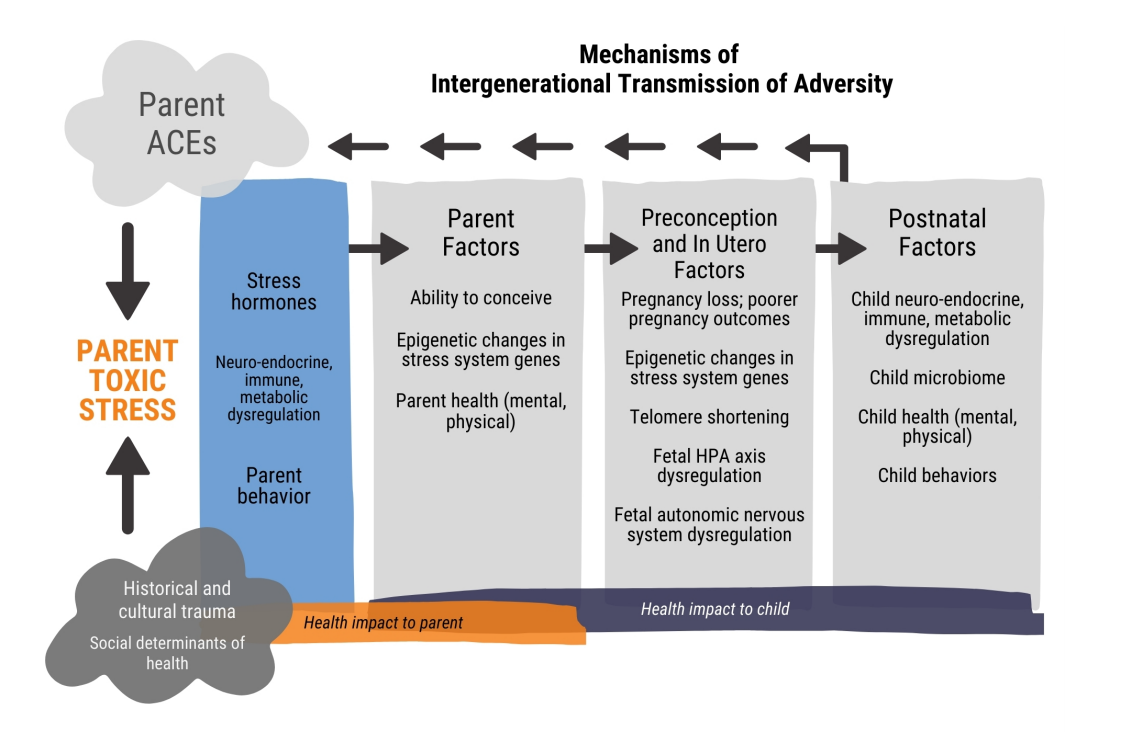

For example, children with many ACEs often have parents with many ACEs, and the intergenerational transmission of toxic stress can perpetuate and exacerbate inequities in health, achievement, socioeconomic mobility, and mortality.

However, “community trauma is not just the aggregate of individuals in a neighborhood who have experienced trauma,” according to a report from the Prevention Institute.

When a community is traumatized, several inter-related components are undermined and damaged so they begin to perpetuate the problems rather than protect the community.

According to the Prevention Institute, trauma manifests at the community level as:

- Intergenerational poverty

- Relocation of businesses and jobs

- Limited employment and long-term unemployment

- Government and private disinvestment

- Damaged, fragmented or disrupted social relations, particularly intergenerational relations

- Damaged or broken social networks and infrastructure of social support

- The elevation of destructive, dislocating social norms that promote or encourage violence and unhealthy behaviors rather than community-oriented positive social norms

- A decreased sense of collective political and social efficacy

- Deteriorated environments and unhealthy, often dangerous, public spaces with a crumbling built environment

- The high availability of unhealthy products, such as alcohol

“Families who live in distressed neighborhoods [often] face a higher cumulative dose of adversity and a lower cumulative dose of buffering relationships and environments, resulting in increased allostatic load (the cumulative biological impacts of repeated exposure to adversity) and increased risk for toxic stress,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states.

“We now understand that a key mechanism by which ACEs lead to increased health risks is through a health condition called the toxic stress response,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states.

However, there is no diagnostic entity that describes the pervasive effects of toxic stress on child development and lifelong health. Neither are toxic stress, nor developmental trauma nationally recognized as conditions, disorders, or diseases.

Worse, when it comes to diagnosing conditions, disorders, and diseases, the current standards don’t include many of the ACEs mentioned above.

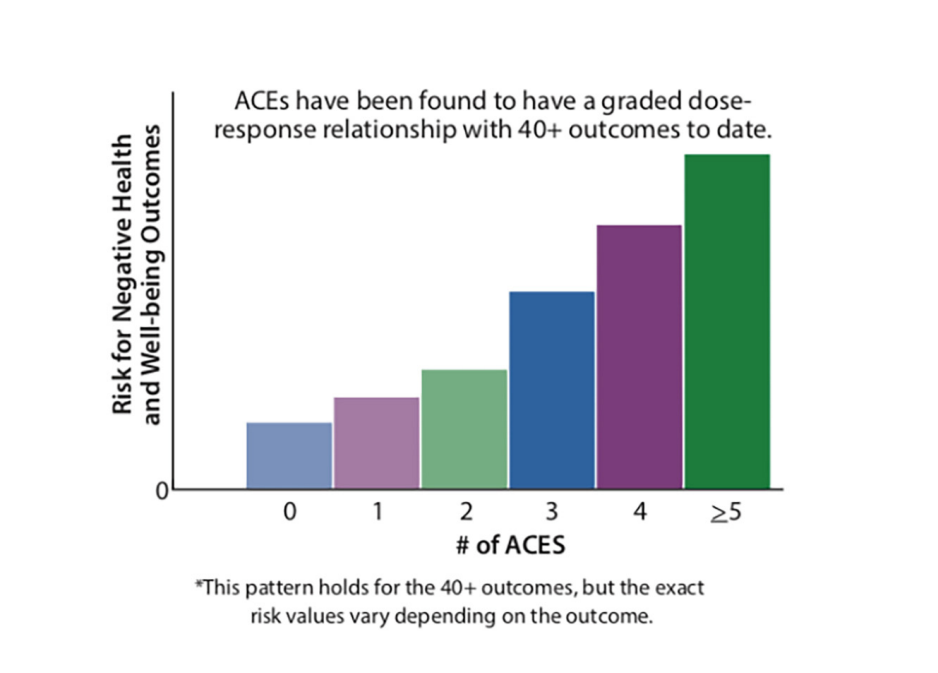

This is particularly problematic because ACEs are prevalent and there is a dose-response relationship between the number of ACE categories experienced and successively increasing risk of numerous negative health and social outcomes.

What is a Dose-Response Relationship and What Does it Mean for ACEs and Toxic Stress?

A dose-response relationship is one in which increasing levels of exposure are associated with either an increasing or decreasing risk of the outcome.

For example, there is a well-researched and recognized dose-response relationship between smoking—the exposure—and lung cancer—the outcome.

An increase in the number of cigarettes smoked per day causes an increase the risk of lung cancer.

There is a dose-response relationship between ACEs—the exposure—and numerous negative social and health outcomes—the outcome.

“ACEs have been found to have a graded dose-response relationship with 40+ outcomes,” the roadmap states.

A study of the following 15 health and socioeconomic outcomes found that people who experienced four or more ACEs accounted for a disproportionate share of the preventable fraction of all of the outcomes measured, according to a 2019 Vital Signs report from the CDC:

- coronary heart disease

- stroke

- asthma

- chronic obstruction pulmonary disease (COPD)

- cancer (excluding skin cancer)

- kidney disease

- diabetes

- depression

- overweight or obesity status

- current smoking

- heavy drinking

- lack of health insurance

- current unemployment status

- no high school diploma

“It is important to note that ACE exposure alone does not determine or foretell an individual’s future health or life outcomes,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states. “Rather, the risks associated with ACE exposure are modulated by multiple factors, such as biological susceptibility, which includes genetic material inherited from one’s parents, and protective factors, such as supportive relationships, environments, and community resources.”

What are Protective Factors for Toxic Stress?

Protective factors for toxic stress and developmental trauma include intrinsic or extrinsic conditions or attributes that mitigate risk for toxic stress, such as:

- curiosity and interest in learning

- ability to pay attention and persist in completing tasks

- ability to regulate emotions and behavior

- feeling cared about and heard when things are hard

- having a sense of belonging in school and in the community

- biological factors like differences in telomere length and the serotonin transporter gene

Buffering relationships are crucial protective factors against ACEs and toxic stress. A nurturing parent or caregiver can turn potentially toxic stress into tolerable stress, reducing the harms of toxic stress and developmental trauma.

Watch this video with numerous neuroscientists, such as Bruce Perry, MD, Daniel Siegel, MD, and Marti Glenn, PhD about the importance of relationships in healing from toxic stress and developmental trauma.

“We are neuro-biologically designed to reach out and seek relationships with other people, and when we have these opportunities to form healthy relationships with family, neighbors, coworkers, and with members of the community, we are healthy,” Perry said. “When we don’t have those opportunities, we literally are physiologically at risk.”

Other factors that reduce the likelihood of developing a toxic stress response include:

- freedom from discrimination

- supportive friend networks

- safe neighborhoods

- access to mental, physical and behavioral healthcare

- high-quality nutrition

- high-quality child care

- economic security

“Accumulating positive experiences during childhood can buffer the developing brain and body from the harmful effects of stress—in other words, they build resilience,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states. “At the molecular level, resilience arises from a combination of neural, hormonal, immune, metabolic, epigenetic, and genetic factors that interact with environmental influences and foster an individual’s ability to adapt in a healthy manner.”

What are the Biological Impacts of ACEs and Toxic Stress?

ACEs and toxic stress disrupt multiple biological symptoms and negatively impact health.

Neurologic and neuroendocrine effects. Disruption to neurologic and neuroendocrine systems can result in heightened or blunted stress sensitivity; increased fear responsiveness, impulsivity, and aggression; impaired executive function; and difficulty with learning and memory.

According to Burke Harris’ roadmap:

- Biological responses: Both the HPA and SAM systems are normally active at baseline levels.But in response to stress, activity intensifies. When activated too frequently or for too long, these systems can become dysregulated.

- Reduced effectiveness: Chronic stress not only activates the stress response repeatedly, but gradually impairs feedback inhibition, compromising an organism’s capacity to recover back to baseline after a stressor.

- Depression, anxiety, ADHD, and Alzheimer’s: Changes to the brain’s threat response, impulse control, motivation and reward pathways, and pain perception mechanisms are associated with toxic stress and are believed to contribute to increased risk for numerous neuropsychiatric disorders.

- Brain architecture: Toxic stress is associated with structural and functional changes in brain architecture, including many brain regions, such as the amygdala (which governs fear and emotion), hippocampus (memory), prefrontal cortex (executive function), and mesolimbic dopamine system (reward and motivation).

- Amygdala: The amygdala, with its role in threat detection, fear, and anxiety, has been measured to be larger and more active in people who exhibit anxiety due to experiencing early childhood adversity.

- Prefrontal cortex and hippocampus: The hippocampus and prefrontal cortex have been documented in functional neuroimaging studies to be smaller and less active in individuals with a history of ACEs, and these changes are associated with difficulty with learning, memory, attention, impulse control, and executive functioning.

- Reward system: In toxic stress, the reward system can change in complex ways. One such change is a reduction in dopamine signaling, leading to less intrinsic motivation to perform routine activities, which also become less rewarding, with a predisposition toward mood disorders like depression. These changes in reward circuitry may also increase the likelihood of engaging in risky behaviors such as substance use.

- Pain circuitry: The combination of greater awareness of pain due to changes in specific circuits and hypersensitivity in its perception due to changes in other circuits results in consequences such as increased susceptibility to acute and chronic pain disorders.

Immunological and inflammatory effects. Disruption to immunological and inflammatory systems can result in increased risk of infection, autoimmune disorders, cancers, and chronic inflammation; cardiometabolic disorders; and changes in growth, development, and basal metabolism.

According to Burke Harris’ roadmap:

According to Burke Harris’ roadmap:

- Infection and inflammation: Chronic stress alters the response to adrenaline and cortisol signaling in the bone marrow, where immune cells are made, resulting in newly born immune monocytes that are proinflammatory and resistant to cortisol’s anti-inflammatory signaling.

- Infection and inflammation: Stress can also impact the early establishment of gut bacteria, known as the microbiome, which in turn influences the generation of certain immune cells in bone marrow for essential inflammatory responses.

- Heart attack and stroke: Acute stress is associated with changes in endothelial cell function, increased arterial stiffness, vessel wall damage, increased blood viscosity, and/or a hypercoagulable state‚ all of which promote increased risk of blood clots.

- Asthma: At the molecular level, early adversity is associated with lower concentrations of the β-2 adrenergic receptor, which is the molecular target of a first-line medication for asthma exacerbations called albuterol, and lower concentrations of the glucocorticoid receptor, targeted by steroid treatments like prednisone. Due to the receptors’ downregulation, these standard asthma treatments may be less effective in individuals with ACEs.

- Cancer: Chronic inflammation may heighten the risk of cancer through multiple mechanisms, including increasing the DNA mutation rate and increasing new blood vessel growth (angiogenesis), which funnels nutrients to tumors. Once a cancer has developed, chronic inflammation can promote its transformation and spread by interfering with normal anti-tumor mechanisms, increasing cytokine production, and creating cancer-protective micro-environments.

- COVID-19: Toxic stress physiology may increase risk of contracting or dying from COVID-19, either through dysregulation of the immune response and/or through increased burden of ACE-associated health conditions (AAHCs), which may predispose to a more severe COVID-19 disease course.

Families in California experiencing the severe economic consequences resulting from the coronavirus can download a new one-pager, Coping with Stress During the COVID-19 Pandemic, in English and Spanish.

Endocrine and metabolic effects. Disruption to endocrine and metabolic systems can result in increased risk of overweight, obesity, cardiometabolic disorders, and insulin resistance.

According to Burke Harris’ roadmap:

- Metabolic syndrome: Toxic-stress-related inflammation is one cause for increased risk of metabolic syndrome after adversity. Metabolic syndrome describes a clustering of health conditions, including high blood pressure, high fasting blood sugar, insulin resistance, excess abdominal fat, abnormal cholesterol, or abnormal triglyceride levels, and it is more likely to occur in people who have experienced adversity during childhood.

- Overweight and obesity: Changes in brain reward signaling pathways, as well as metabolic hormones which govern feeding and hunger cues, may predispose to overconsumption of high-fat, high-sugar foods.

- Diabetes: Type 2 diabetes is caused by dysregulated insulin production by the pancreas and reduced sensitivity (insulin resistance) exhibited by cells throughout the body and brain. Toxic stress can increase risk for these outcomes. Stress may even change patterns of insulin secretion intergenerationally, leading subsequent generations to be more susceptible to diabetes.

- Cardiovascular and kidney disease: Several studies have suggested a convergent mechanism for cardiovascular and kidney disease through dysregulation of endothelin-1, which plays a role in blood pressure and arterial stiffness and is activated in response to stress.

Epigenetic and genetic effects. The process of epigenetics controls genes like an “on-off” switch, determining if and when genes will be read. Disruption to epigenetic and genetic regulatory functioning can result in changes in the way DNA is read and transcribed which can alter the regulation of gene expression that governs multiple biological processes. It may lead to higher rates of cancer, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, and premature death.

According to Burke Harris’ roadmap:

- Premature cellular aging: Stress, especially in early and middle childhood, leads to shortened telomeres and premature cellular aging.

- Telomeres: Telomeres are regions at the ends of DNA strands that protect them from degradation, and because telomeres are shortened over time, they act as a countdown clock to cellular senescence and death. As cells age, their functioning declines.

- Premature death: For people with toxic stress, aging faster is not a metaphor; those with six or more ACEs live, on average, almost 20 years less than those with none.

- Reversibility: Building resilience and targeted treatments can reverse or prevent negative epigenetic changes resulting from childhood adversity, as well as subsequent biological risks.

What Are Two Examples of the Biological Impacts of ACEs and Toxic Stress?

One example is sleep.

“Sleep disturbances are among the most common and nonspecific outcomes of childhood adversity,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states. “Disordered or reduced sleep duration is associated with heart disease, hypertension, obesity, diabetes, cancer, decreased cognitive performance, depression, anxiety, inflammatory diseases, infection risk, and all-cause mortality.”

For example:

- Adversity and toxic stress may impair sleep by dysregulating cortisol and sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activity.

- Disruptions in sleep are associated with altered levels of cortisol, as well as increases in norepinephrine, epinephrine, and blood pressure.

- Poor sleep alters other endocrine and metabolic functions and is associated with elevated insulin and blood glucose levels and altered brain glycogen.

- Sleep deficiency disturbs immune system homeostasis and is associated with chronic, low-grade inflammation.

Another example is nutrition.

Although the specific dose-response relationship between ACEs and nutrition is unknown, the relationship is complex, multifaceted, and bidirectional with food behavior affecting stress and stress affecting food behavior.

Malnutrition/undernutrition can activate the physiologic stress response and patients with eating disorders have higher cortisol levels.

But the stress response can also affect food behavior, contributing to eating disorders, malnutrition, and maladaptive coping strategies.

Researchers have found different time courses for the stress hormones adrenaline and cortisol, suggesting a decreased appetite may occur early—second to minutes—in the stress response, and an increased appetite may occur later—hours to days—in the stress response.

Both under- and overeating may be neurobiological adaptations to stress, according to the roadmap.

Among pregnant women, food insecurity—a risk factor for toxic stress response—is linked to maternal perceived stress and to increased fat intake.

Increased preference for high-fat and high-sugar foods is a maladaptive coping strategy associated with stress and can led to increased inflammation, infection risk, and obesity. Obesity is also associated with physiological stress response.

How do ACEs and Toxic Stress Affect the Health of Future Generations?

Both risk factors and protective factors can accrue over generations directly and indirectly through parenting behaviors, positive experiences, societal factors, and the biological impacts of historical traumas.

“Intergenerational transmission of toxic stress occurs when adverse experiences alter parental biology or behavior in ways that affect the development and health of their children,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states. “This includes changes to parental and child neuro-endocrine-immune-metabolic and genetic/genetic regulatory function, in ways that matter for pre-conception health, and also influence pregnancy, birth, infant, and child health outcomes.”

Parental biology and parenting behavior can result in many of the risk factors for and biological impacts of toxic stress mentioned above.

For example, higher levels of maternal norepinephrine are linked with preterm delivery, and elevated maternal cortisol concentrations can impair the development of the baby and may alter mechanisms of the placenta necessary to regulate fetal cortisol which are linked to dysregulated infant cortisol responses to a stressor.

“Maternal stress and associated endocrine and immune system dysfunction may alter fetal brain structures involved in the stress response, including the hippocampus and amygdala, preprogramming the child for greater stress reactivity,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states.

It isn’t just adversity during pregnancy that impacts fetal development.

Experiencing adversity in childhood is linked with increased production of stress hormones during pregnancy and increased risk for low birth weight, preterm birth, hospitalizations during pregnancy, premature contractions, and shorter telomere length in infants.

“A growing body of research is finding that interventions such as supportive parenting, aerobic exercise, and nutrition may reduce stress and protect or even lengthen telomeres,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states.

Because toxic stress disrupts the immune system, for example, inflammation is one mechanism that passes the biological impacts of toxic stress to the next generation.

“Fetal exposure to inflammatory proteins and cortisol has been associated with epigenetic changes (miRNA expression and DNA methylation) in the fetal brain, including alterations in neurotransmitter levels, cell survival, growth of new brain cells, connections between brain cells, and myelination (a process by which a fatty sheath surrounds axons of neurons and speeds up signaling),” Burke Harris’ roadmap states.

Toxic-stress-related epigenetic changes that occur throughout life may be transmitted to the next generation through both the mother and the father, known has historical and cultural trauma.

Current and historical racism and structural inequities, including lack of community investment, educational resources, economic opportunities, and transportation availability, all affect childhood development and lifelong health.

“Bringing the lens of historical trauma to trauma work “creates an emotional and psychological release from blame and guilt about health status, empowers individuals and communities to address the root causes of poor health, and allows for capacity-building unique to culture, community, and social structure,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states.

The biological impacts and intergenerational effects of ACEs and toxic stress result in some of the most common and serious health and social problems facing America today.

What are the Health and Social Conditions Associated with ACEs and Toxic Stress?

ACEs are strongly associated with nine of the 10 leading causes of death:

- heart disease

- cancer

- accidents/unintentional injuries

- chronic lower respiratory disease

- stroke

- Alzheimer’s disease or dementia

- Diabetes

- kidney disease

- suicide attempts

“Individuals with four or more ACEs are two to three times as likely to develop ischemic heart disease, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and cancer, and 11 times as likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias, compared to those with no ACEs,” the roadmap states.

Additionally, individuals with four or more ACEs are 37 times as likely to attempt suicide.

ACEs are also associated with some of our most pressing social problems, including learning, developmental, and behavior problems, high school noncompletion, unemployment, poverty, homelessness, and felony charges.

“While most individuals with significant ACEs do not encounter the criminal justice system, exposure to ACEs is a well-documented risk factor for justice involvement, which may be an important indicator of severe and untreated toxic stress,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states.

Many of these social problems are risk factors for toxic stress and contribute to the intergenerational transmission of adversity.

ACEs are also associated with the following health and social conditions among adults:

- cardiovascular disease

- tachycardia

- stroke

- diabetes

- obesity

- hepatitis or jaundice

- cancer

- arthritis

- memory impairment

- kidney disease

- headaches

- chronic pain

- fibromyalgia

- unexplained somatic symptoms including somatic pain

- skeletal fractures

- physical disability requiring assistive equipment

- depression

- suicide attempts

- suicide ideation

- sleep disturbance

- anxiety

- panic and anxiety

- post-traumatic stress disorder

- illicit drug use

- injected drug, crack cocaine, or heroin use

- alcohol use

- cigarettes or e-cigarettes use

- cannabis use

- teen pregnancy

- sexually transmitted infections

- violence victimization

- violence perpetration

Adults with four or more ACEs are three to four times more likely to experience anxiety and depression than adults with zero ACEs.

Adults with four or more ACEs are five to six times more likely to use illicit drugs, cigarettes, and alcohol.

Adults with four or more ACEs are seven to eight times more likely to experience violence victimization and perpetration.

Below is a list of ACE-associated health conditions (AAHC) among children:

- asthma

- allergies

- dermatitis and eczema

- urticaria

- increased incidence of chronic disease, impaired management

- unexplained somatic symptoms, such as nausea/vomiting, dizziness, constipation, headaches

- enuresis

- encopresis

- overweight and obesity

- failure to thrive

- poor growth

- psychosocial dwarfism

- poor dental health

- increased infections

- later menarche

- sleep disturbances

- developmental delay

- learning and/or behavioral problems

- repeating a grade

- not completing homework

- high school absenteeism

- not graduating from high school

- aggression, physical fighting

- depression

- ADHD

- anxiety

- conduct/behavior disorder

- suicidal ideation

- suicide attempts

- self-harm

- first us of alcohol at < 14 years

- first use of illicit drugs at < 14 years

- early sexual debut

- teen pregnancy

Children with four or more ACEs are two to three times more likely to repeat a grade have early sexual debut and experience poor dental health and allergies than children with zero ACEs.

Those with three or more ACEs are 4.5 times as likely to have ADHD, depression, anxiety, or conduct/behavior disorder and more than nine times as likely to have unexplained somatic symptoms, such as nausea/vomiting, dizziness, constipation, or headaches.

Children with four or more ACEs are six to seven times more likely to use alcohol before age 14 and to have high school absenteeism.

Those with four or more ACEs are 32 times more likely to have learning and/or behavior problems.

Latino children with four or more ACEs face 4.5-fold increased risk of asthma compared to children with zero ACEs.

Adults with four or more ACEs are 1.6 times more likely to experience sleep disturbances.

“Exposure to ACEs can also set up transmission of health risks across generations by altering gene expression (epigenetics) in parents to be, which can affect the development and health of their children, and future generations to come,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states.

“In sum, severe, frequent, and/or chronic adversity in childhood, in the absence of sufficient buffering factors, is a root cause of the most prevalent, debilitating, and costly health conditions in California. Acting through the toxic stress pathway, these childhood adversities also perpetuate and exacerbate socially rooted inequities in health, achievement, socioeconomic mobility, and mortality for generations to come.”

What are the Financial Impacts of ACEs and Toxic Stress?

When estimating the economic costs of health conditions associated with toxic stress, analysts often look at healthy years of life lost due to premature death and to disability for people living with the health condition or its consequences.

Thus, it is important to understand what fraction of health conditions are associated with ACEs.

For example, one study found that the fraction of the 10 major causes of ill health—cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, anxiety, depression, harmful alcohol use, illicit drug use, smoking, and obesity—attributable to ACEs ranged from 7.5% to 41.1%.

Another study found that 30% of cases of anxiety and 40% of cases of depression were attributable to ACEs.

“Costs due to cardiovascular disease attributable to ACEs were substantially higher than for the other causes of ill health included in the study,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states.

The health consequences attributable to ACEs in 2017 resulted in an estimated yearly loss of $1.3 trillion in North America and Europe.

In California, the annual health burden of ACEs is estimated to be $112.5 billion for eight ACE-associated health conditions—asthma, arthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, depression, cardiovascular disease, smoking, heavy drinking, and obesity.

However, costs extend beyond health burden and healthcare.

“US lifetime systems-level costs for child abuse and neglect cases substantiated by Child Protective Services (CPS) were $4.5 billion in child welfare, $3.9 billion in criminal justice, and $4.6 billion in special education (based on 2008 data),” Burke Harris’ roadmap states.

In California, annual health burden and healthcare costs attributed to ACEs are estimated at $112.5 billion.

Considering only substantiated child abuse and neglect in California, one study estimated annual state costs at $15.3 billion total for the following areas:

- $919 million in education

- $787 million in welfare

- $545 million in criminal justice

- $13 billion in lost economic productivity

The report also estimates $19.3 billion for the overall annual cost of substantiated child abuse and neglect cases in California, with:

- $3.8 billion in healthcare costs

- $207 million in fatalities

“Ongoing and future studies on the costs of ACEs could include total costs associated with illness and disability from all AAHCs, lost economic productivity, school failure and noncompletion, learning and developmental problems requiring interventions like special education, involvement in criminal justice, child welfare, and public support service systems, all shown to be higher in those with significant ACEs, toxic stress, and/or AAHCs,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states.

The health, social, and financial impacts of ACEs and toxic stress are particularly problematic because ACEs are prevalent.

How Prevalent are the ACEs that Cause Toxic Stress?

According to a recent survey of 214,157 adults from 23 states, 61.6% reported at least one ACE and 15.8% reported four or more, Burke Harris’ roadmap states.

In California, 62.3% of adults have experienced at least one ACE. 16.3% have experienced four or more ACEs.

Unfortunately, groups that are racially marginalized, like Latino and Black populations, low-income populations, and non-high school graduates are disproportionately burdened by ACEs.

A study of 5,117 Latino adults in four major US cities found that 77.2% have experienced at least one ACE, and 28.7% have experience four or more, according to a Salud America! research review.

“Adults enrolled in California’s Medicaid program (Medi-Cal) are 1.3 times as likely to report having experienced four or more ACEs, compared to those with employer-based or private insurance,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states.

Less than 4% of California children who experience zero ACEs live with a family that experiences food insecurity compared to 20.9% of children with two or more ACEs.

While roughly 18% of all California children live with a family that experiences serious economic hardship to meet basic needs, nearly half (49.4%) of children who experience two or more ACEs do.

Latinos face higher rates of poverty and incarceration than whites.

In a 2017 sample of adults, Latino adults were three times as likely to be incarcerated as White adults, according to the roadmap.

Adversity, like family incarceration is particularly problematic because it contributes to the intergenerational accumulation of ACEs.

“One study found that half of incarcerated youth had experienced four or more ACEs,” according to the roadmap.

“While most individuals with significant ACEs do not encounter the criminal justice system, exposure to ACEs is a well-documented risk factor for justice involvement, which may be an important indicator of severe and untreated toxic stress,” the roadmap states.

What Can We Do About Toxic Stress?

Share our Salud America! team’s 11-part exploration into the important recommendations in Dr. Nadine Burke Harris’ roadmap to address ACEs and toxic stress:

- Toxic Stress and its Lifelong Health Consequences. Toxic stress is a public health crisis that has lifelong impacts on physical, mental, and behavioral health. (current article)

- We Need to Recognize Toxic Stress as a Health Condition with Clinical Implications. Health experts are pushing to elevate toxic stress and developmental trauma on national research and policy agendas.

- Cut Toxic Stress with 3 Types of Public Health Prevention Interventions. Preventing toxic stress requires a three-level public health intervention approach.

- How to Use Healthcare Strategies to Address Toxic Stress. In clinics, hospitals, and other healthcare settings, workers can provide universal trauma-informed care and more.

- Using Public Health Strategies to Address Toxic Stress. When it comes to ACEs and resulting toxic stress, the public health sector can play a critical role by strengthening economic support, positive family relationships, and social services.

- How to Use Social Service Strategies to Address Toxic Stress. We need trauma-informed training for social workers, as well as family-friendly workplaces and home visits.

- Toxic Stress in Early Childhood and How to Prevent It. Early childhood is a key time for preventing ACEs and toxic stress.

- Toxic Stress in Justice and How to Address It. Encounters with police are “intrinsically stressful and potentially traumatic,” especially for youth of color.

- Toxic Stress in Education and How to Address It. ACEs and toxic stress can hinder a person’s learning and school success.

- California’s Epic Response to Toxic Stress and ACEs. California, already leading the nation in addressing ACEs, is making inroads to address toxic stress.

- 5 Upstream Ways You Can Take Action to Address Toxic Stress. Here are ways you can take action to address toxic stress.

“ACEs and toxic stress are a public health crisis in California and throughout our nation. But ACEs are not destiny,” said Burke Harris in a news release. “I am thrilled to share this report as a roadmap for prevention, early detection and cross-sector, coordinated interventions to address ACEs and toxic stress in a systematic way. None of these strategies are sufficient alone and each extends the reach of others.”

By The Numbers

142

Percent

Expected rise in Latino cancer cases in coming years