Share On Social!

Through prolonged activation of the toxic stress response, adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), like neglect and poverty, disrupt the development of brain architecture and other organ systems and are strongly associated with some of the most common and serious health conditions facing our society.

This means toxic stress is a health condition with clinical implications.

The healthcare system can play a central role in preventing, detecting, and mitigating toxic stress.

That’s why, in December 2020, Dr. Nadine Burke Harris released her Roadmap for Resilience: The California Surgeon General’s Report on Adverse Childhood Experiences, Toxic Stress, and Health.

Salud America! is exploring this as part of its 11-part series on toxic stress.

Below are primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention strategies for the healthcare sector to address toxic stress among Latino and all people.

Primary Prevention Strategies in Healthcare

Primary prevention includes efforts that target healthy individuals and aim to prevent harmful exposures and behaviors from ever occurring.

A critical strategy for primary prevention of ACEs and toxic stress in the healthcare setting begins with the universal implementation of trauma-informed care (TIC):

- Understanding the prevalence of trauma and adversity and their impacts on health and behavior;

- Recognizing the effects of trauma and adversity on health and behavior;

- Training leadership, providers, and staff on responding to patients by incorporating best practices for trauma-informed care;

- Integrating knowledge about trauma and adversity into policies, procedures, practices, and treatment planning; and

- Resisting retraumatization by approaching patients who have experienced ACEs or other adversities with nonjudgmental support.

The following key principles of trauma-informed care can guide healthcare providers and staff:

- Establish the physical and emotional safety of patients and staff.

- Build trust between providers and patients.

- Recognize and respond to signs and symptoms of trauma exposure on physical and mental health.

- Promote patient-centered, evidence-based care.

- Ensure provider and patient collaboration by bringing patients into the treatment process and discussing mutually agreed-upon goals for treatment.

- Provide care that is sensitive to the patient’s racial, ethnic, and cultural background, and gender identity.

The healthcare setting provides an opportunity to promote family strengths. This can help patients develop skills and capacities necessary to increase positive, buffering experiences to prevent ACEs and toxic stress.

Healthcare settings can also enable patients and families to build cumulative protective factors, or positive childhood experiences (PCEs). Among those who have experienced ACEs, PCEs can decrease risk of developing the toxic stress response.

Efforts to prevent discrimination and social oppression are critical in preventing toxic stress in children and families. These include: using evidence-based screening tools incorporating perceived and experienced racism, and offering appropriate referrals; assessing strengths and protective factors to mitigate exposure to racism; providing youth and families with guidance on recognizing and responding to racism; and training clinic and office staff in culturally competent care.

“To enable lasting change, healthcare-based innovations must be closely coordinated with cross-sector response, practice transformation, research and innovation, and public education efforts,” Burke Harris’ report states.

Cross-sector coordination with schools, child care, justice, social services, and public health can emphasize patient education, anticipatory guidance, and linkages or referrals to resources, like home visiting programs, quality child care, family violence prevention, and legal supports.

Integrating primary care and mental and behavioral health in one setting and coordinating with schools and child welfare agencies can support protective exposures through trusted adults and enrichment activities. This can also ensure that referrals address root causes of adversity through services such as stress management, parenting support, and assistance with financial, housing, and food security.

Because limited access to healthcare is a serious issue in the U.S., particularly for Latino and Black populations, ensuring access to high-quality healthcare is another key component of primary prevention of ACEs and toxic stress.

Secondary Prevention Strategies in Healthcare

Secondary prevention, also known as early detection, involves screening to identify risk factors and/or diseases in the earliest stages.

Screening can enable more effective referrals, guidance, and support around preventing and addressing cumulative risk for toxic stress.

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) all recommend early screening for sources of toxic stress and coordination of a cross-sector response to mitigate the harmful effects of early adversity.

Early detection is key to improving health outcomes, and primary care provides a unique opportunity to interrupt the biological impacts of early adversity.

Unfortunately, there are no nationally agreed-upon biomarkers, tests, or diagnostic criteria for assessing ACEs and toxic stress.

While some potential biomarkers have been proposed, such as markers of inflammation, stress, altered metabolism, cellular aging, and epigenetic regulation, efforts are underway to develop reliable clinical biomarkers that may inform diagnosis, prognostic precision, and therapeutic targets in identifying and intervening on toxic stress.

“In the absence of clinical diagnostic criteria, the combination of ACE score and the presence or absence of AAHCs may serve as a somewhat crude, but useful, proxy for the likely presence of a toxic stress response,” Burke Harris’ report states.

Currently, comprehensive screening involves assessing three mechanisms:

- Adversity/trauma, using the original 10 ACEs categories as well as other potential risk factors for toxic stress, such as discrimination, poverty, community violence, food and housing insecurity, and bullying;

- Clinical manifestations or medical consequences of toxic stress, known as ACE-Associated Health Conditions (AAHCs); and

- protective factors.

“Pending the development of confirmatory diagnostic criteria and/or biomarkers, the evidence supports characterizing a patient as being at low, intermediate or high risk of manifesting a toxic stress response,” Burke Harris’ report states.

“Pending the development of confirmatory diagnostic criteria and/or biomarkers, the evidence supports characterizing a patient as being at low, intermediate or high risk of manifesting a toxic stress response,” Burke Harris’ report states.

The Pediatric ACEs and Related Life-events Screener (PEARLS) test, for example, is used by healthcare providers in California to assess children for the 10 original categories of ACEs—as well as seven additional categories of trauma.

Developed by the Bay Area Research Consortium on Toxic Stress and Health (BARC), PEARLS has diagnostic criteria that characterize a patient’s risk of manifesting a toxic stress response based on the 10 original ACE categories. A score of 0 indicates low risk, a score of 1-3 without associated health conditions indicates intermediate risk, a score of 1-3 with associated health conditions indicates high risk, and a score of 4+ with or without associated health conditions indicates high risk.

Screening may begin during prenatal care and continue through adulthood, with an emphasis on promoting equity in ACEs screening and response to reduce disparities in screening, referral patterns, and treatment outcomes.

While further studies are needed, current evidence suggests that screening and intervention for toxic stress may be associated with improved healthcare utilization and could save tens of billions in medical expenditures annually.

In California alone, ACEs cost $112.5 billion overall annually, according to Burke Harris’ report. Read more about the financial costs of ACEs and toxic stress here.

Burke Harris’ report provides a detailed rationale for screening for ACEs and toxic stress in primary care. It explains how the 10 public health principles for optimal population-based screening efforts are applicable to toxic stress risk assessment and intervention.

The report also provides system-level implementation considerations. For example, state and local policymakers, payers, and leaders of community collaborations can coordinate the many interlocking systems, policies, funding streams, and programs that affect the capacity of healthcare providers and communities.

After identifying individuals with ACEs and increased risk of toxic stress, clinical response should include:

- Applying principles of trauma-informed care, such as establishing trust, safety, and collaborative decision-making.

- Supplementing usual care for AAHCs by providing patient education on toxic stress and offering strategies to regulate the stress response including: supportive relationships; high-quality, sufficient sleep; balanced nutrition; regular physical activity; mindfulness and meditation; access to nature; and mental healthcare, including psychotherapy or psychiatric care, and substance use disorder treatment, when indicated.

- Validating existing strengths and protective factors.

- Referrals to patient resources or interventions, such as educational materials, social work, school agencies, care coordination or patient navigation, and community health workers.

- Follow up as necessary, using the presenting AAHCs as indicators of treatment progress.

When primary care providers address the role of the toxic stress response in mental, behavioral, and physical health conditions in adult patients, they can reduce vectors for the intergenerational transmission of adversity, which can improve family outcomes.

“Providers may refer families to public assistance programs as needed because strengthening financial security is an important multigenerational strategy to reduce ACEs and toxic stress and enhance families’ ability to provide buffering relationships and environments,” Burke Harris’ report states.

Tertiary Prevention Strategies in Healthcare

Tertiary prevention, also known as early intervention or treatment, includes efforts that target individuals who have already developed a disease or social outcome.

To support individuals who are assessed at intermediate or high risk for toxic stress, the primary care setting can implement tools and interventions that target the underlying biological mechanisms of toxic stress to reduce the impact of the toxic stress response and improve neuroendocrine-immune-metabolic functioning.

“Health plans and providers should work to identify local resources that are available for referral for ACEs prevention and toxic stress mitigation, as well as to address additional social determinants of health such as housing and food insecurity,” Burke Harris’ report states.

Clinical response begins with key principles of trauma-informed care—mentioned in primary prevention—and includes anticipatory guidance, interventions, and referrals.

The following seven evidence-based strategies for toxic stress regulation can help patients reduce stress and build resilience:

1. Healthy relationships

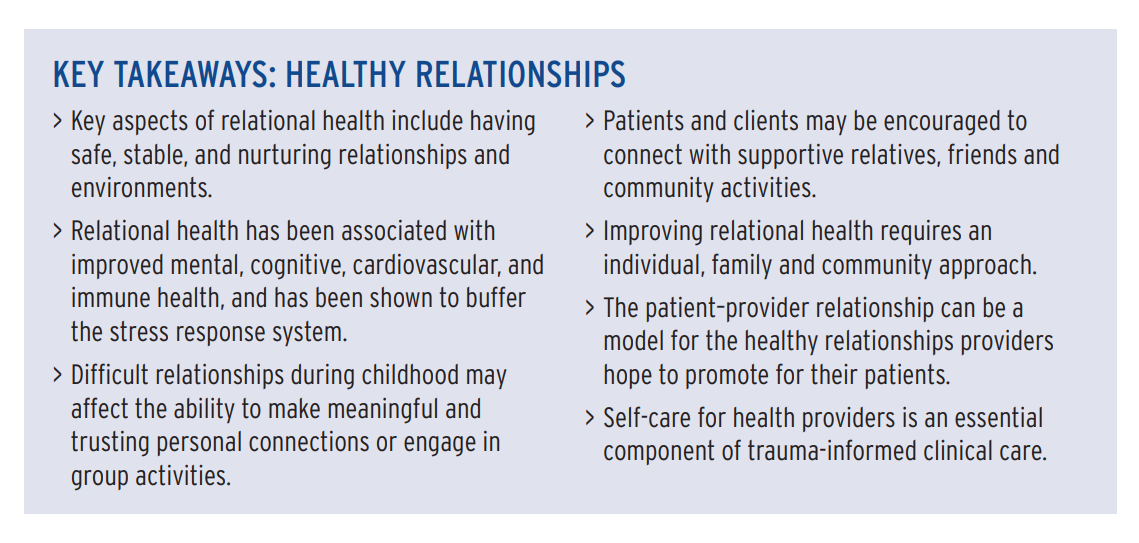

“Research shows that relationships can buffer stress and reduce, or in some cases, eliminate the negative health impacts associated with ACEs,” according to Burke Harris’ report.

For example:

- Responsive caregiving mediates improved cortisol reactivity in children.

- Supportive relationships have been shown to buffer stress-induced cardiovascular reactivity.

- Social support and PCEs have been associated with improved immune responses, including inhibiting inflammation, providing protection against infection, and promoting wound healing.

- Supportive relationships are believed to release the hormone oxytocin which enhances bonding, inhibits the stress response, protects against stress-induced cell death, has anti-inflammatory effects, enhances metabolic homeostasis, and protects vascular endothelium.

Assessment. While there are a number of tools to evaluate attachment and relational health, there are very few screens available for easy use in primary care clinical practice.

Interventions. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends routine anticipatory guidance about relational health and developmentally appropriate play, such as Talk. Read. Sing. and clinic programs such as Reach Out and Read.

Dyadic or two-generation interventions that specifically target addressing parental trauma as a means to improve child outcomes, such as Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up (ABC), Child-Parent Psychotherapy (CPP), and Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT), have been associated with improvement in various markers of neuro-endocrine-immune-metabolic regulation, including cortisol, epigenetic regulation, and brain development.

2. High-quality, sufficient sleep

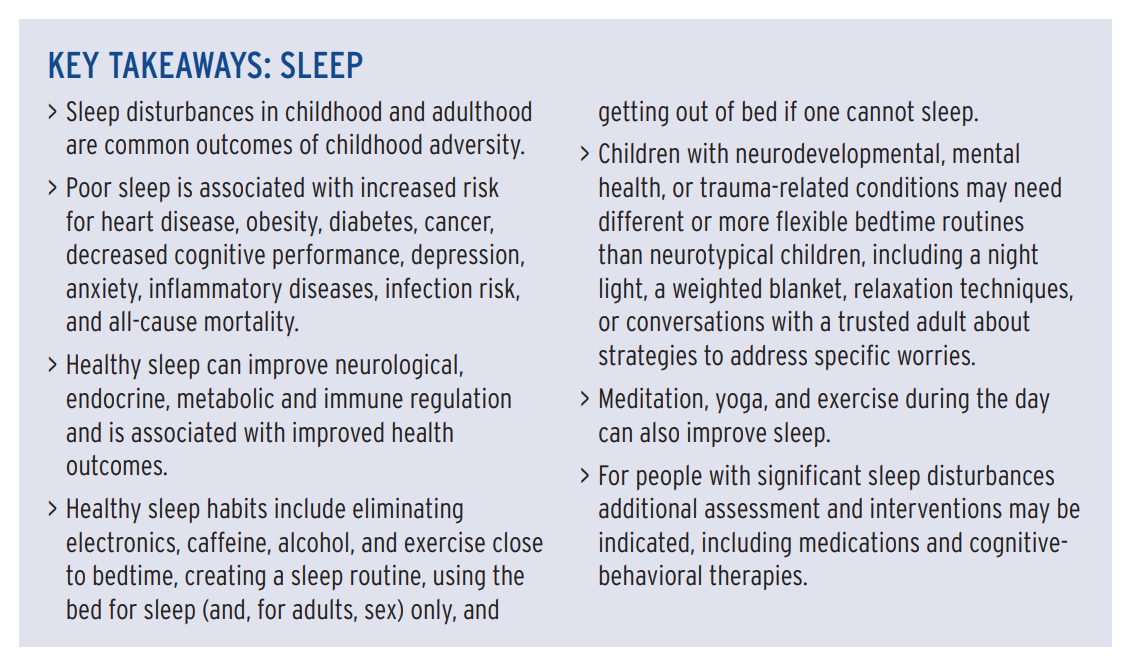

“Disordered or reduced sleep duration is associated with heart disease, hypertension, obesity, diabetes, cancer, decreased cognitive performance, depression, anxiety, inflammatory diseases, infection risk, and all-cause mortality,” according to Burke Harris’ report.

For example:

- Adversity and toxic stress may impair sleep by dysregulating cortisol and sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activity.

- Disruptions in sleep are associated with altered levels of cortisol, as well as increases in norepinephrine, epinephrine, and blood pressure.

- Poor sleep alters other endocrine and metabolic functions and is associated with elevated insulin and blood glucose levels and altered brain glycogen.

- Sleep deficiency disturbs immune system homeostasis and is associated with chronic, low-grade inflammation.

“In children, poor sleep is associated with impairments in neurocognitive development, social emotional skills, physical health, and family functioning,” Burke Harris’ report states.

Assessment. While there are tools to assess sleep, the most pragmatic approach for a busy clinic may be to highlight four key elements:

- patient satisfaction with sleep,

- whether patients feel restored and rested when they wake up,

- whether they have trouble falling asleep initially, and

- whether they have trouble staying asleep or falling back to sleep if they wake up in the middle of the night.

Interventions. “A meta-analysis of sleep interventions for adults without diagnosed sleep disorders found that cognitive and behavioral interventions, including relaxation practices, sleep hygiene, and exercise improved sleep quality,” the Burke Harris’ report states.

Consistent bedtime routines, such as feeding, bath, massage, reading books, rocking, prayer, singing, and listening to music, can decrease bedtime tantrums, improve sleep, child mood, emotional behavioral regulation, mother’s self-reported mood, school readiness, and literacy outcomes, and can be a buffer against parenting stress.

3. Balanced nutrition

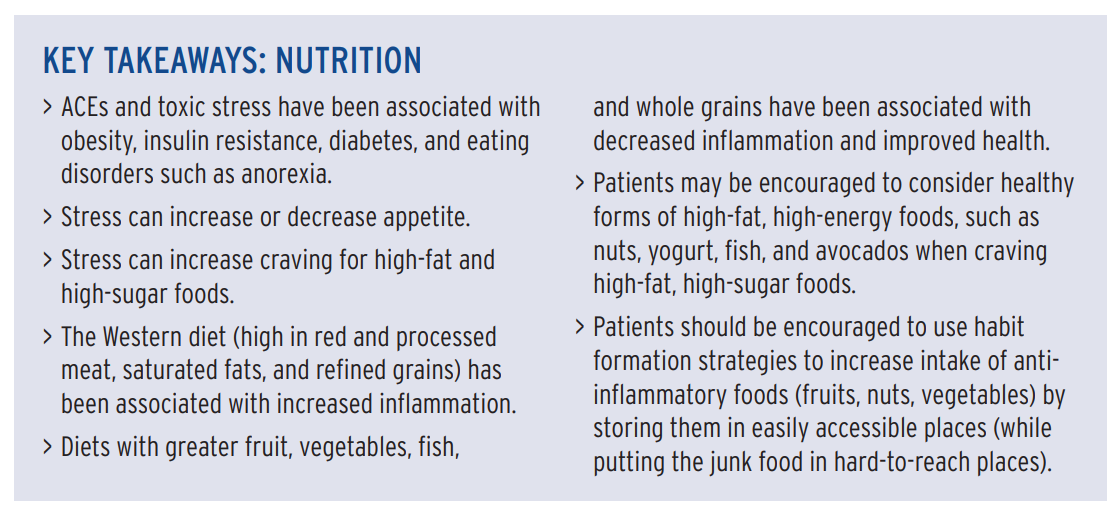

While willpower is often implicated for dietary choices, evidence suggests stress can affect food behavior, such as eating disorders and maladaptive nutritional coping strategies. Stress can also affect digestive processes and metabolism.

Stress can affect food behavior, contributing to eating disorders and maladaptive nutritional coping strategies. Researchers have found different time courses for the stress hormones adrenaline and cortisol, suggesting a decreased appetite may occur early—seconds to minutes—in the stress response, and an increased appetite may occur later—hours to days—in the stress response. Increased preference for high-fat and high-sugar foods is a maladaptive coping strategy associated with stress and can led to increased inflammation, infection risk, and obesity.

In fact, according to Burke Harris’ report, both under- and overeating may both be neurobiological adaptations to stress. Stress can also affect digestive processes and metabolism.

According to Burke Harris’ report:

- Malnutrition/undernutrition can activate the physiologic stress response.

- Patients with eating disorders have been found to have either greater basal cortisol levels or greater cortisol reactivity.

- Maladaptive nutritional coping strategies, including preference for high-fat and high-sugar foods, can lead to increased inflammation or infection risk.

- Diets low in omega-3 fatty acids have been associated with higher levels of anxiety and depression in pregnancy.

Assessment. Patient completion of a 24-hour food recall or a food diary can be useful clinical techniques to assess nutritional status.

Interventions. Because of the complex interplay between food, stress, and neuro-endocrine-immune-metabolic function, nutritional counseling should include consideration of the biological drive for high-fat, high-sugar foods as well as consideration of specific nutritional interventions in decreasing stress and inflammation.

“Nutritional supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids has been found to lower norepinephrine, adrenocorticotropic hormone, plasma cortisol, and body temperature in response to an endotoxin challenge, compared to a placebo,” Burke Harris’ report states.

4. Regular physical activity

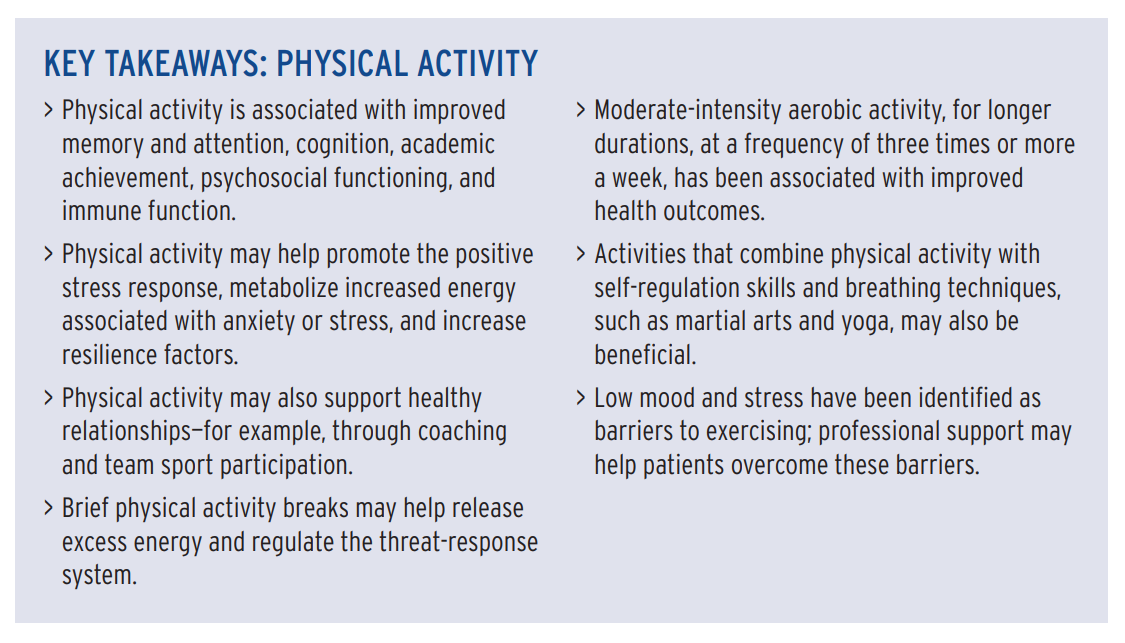

Physical activity increases hippocampal white matter volume, neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity, and blood flow, and releases proteins such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and metabolites that may support brain health.

According to the report, physical activity:

- may help increase resilience factors such as skill development, self-regulation, problem-solving abilities, and a sense of agency;

- can improve sleep, which can improve immune function; and

- is associated with improved memory and attention, cognition, academic achievement, and psychosocial functioning;

However, studies are not uniform in the type, intensity, or frequency of exercise needed to achieve these outcomes.

Interventions:

According to the report:

- Moderate-intensity aerobic exercise three times a week for a minimum of nine weeks has been shown to improve depression.

- Low mood and stress have been identified as barriers to exercising; professional support may help patients overcome these barriers.

- Among patients with PTSD, physical activity may reduce depressive symptoms, PTSD symptoms, anxiety, and stress.

- Physical activity interventions for anxiety were more effective when they included supervised exercise, moderate- or high-intensity exercise, and exercise at a fitness center rather than at home.

- Programs that couple physical activity with self-regulation skills, such as martial arts and yoga, may lead to more improvements in executive functioning.

- Gamification strategies, such as the Behavioral Economics Framingham Incentive Trial, which gamified step goals, can help improve activity levels.

5. Mindfulness and meditation

Mindfulness has been defined as nonjudgmental, moment-to-moment awareness that involves attention, intention, and a kind attitude.

According to the report, mindfulness:

- has been shown to be helpful for people with ACEs and trauma, PTSD, anxiety and depression, executive functioning disorders, pain management concerns, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), sleep problems, and parental stress.

- has been shown to decrease shame and increase acceptance, self-compassion, and empathy.

- is associated with decreased parental stress and an improved caregiver–child relationship.

In the healthcare setting, mindfulness has been found to decrease provider stress and burnout, improve patient-centered care, increase empathy, improve patient satisfaction, and reduce implicit bias.

The American Heart Association (AHA) reports that, given the low costs, low risks, and potential benefits, meditation could supplement routine treatments for cardiovascular disease.

6. Access to nature

“Interacting with nature is associated with decreased diabetes, depression, heart rate and blood pressure, heart disease, and mortality,” Burke Harris’ report states.

For example, according to the report:

- Adding green spaces in low-resourced communities has been associated with reduced crime and violence, improved perception of safety, increased social connections, and reduced depressive symptoms.

- Parks and exposure to nature have been shown to increase play and physical activity, and to decrease screen time.

- A study of park prescriptions at a pediatric primary care clinic in a city found that they increased park visits and physical activity, and were associated with decreased perceived stress, loneliness, and cortisol levels.

However, access to nature is not equal.

For example, Latino communities lack safe, accessible, and culturally relevant green space. Only 1 in 3 Latinos live within walking distance (<1 mile) of a park. Park-less Latinos miss out on space for physical activity, social interaction, and stress reduction, according to a Salud America! research review.

Additionally, the experience of being in nature is different for some for Latinos and some communities of color due to historic and current racism contributing to feelings of lack of safety and lack of inclusion.

Extra efforts must be made to support historically marginalized communities in feeling safe and welcome in nature.

Interventions.

According to Burke Harris’ report:

- Providers can discuss the important link between health and nature and encourage time in nature as a health intervention.

- Park prescriptions can be used in primary care clinics as a way to start a conversation about nature, encourage park usage, and demonstrate the link between nature and health; see parkrx.org.

- Hospitals, schools, and workplaces may be encouraged to increase indoor and outdoor green space.

- Providers can recognize that there may be cultural, community, and policy barriers to equal access to nature. Access to nature is a social justice health issue.

- Patients may be referred to ecotherapy, wilderness therapy, or adventure-based treatment programs.

7. Behavioral and mental healthcare

Integrating behavioral and mental health with primary care can improve health outcomes, improve quality of life, and cut costs.

“Mental and behavioral healthcare can help patients build skills and capacities for resilience, directly address trauma-related symptoms, and scaffold with medications as necessary, all in the context of safe, supportive, and trusting relationships,” Burke Harris’ report states.

Multidisciplinary teams of primary care providers, mental or behavioral health providers, care coordinators, navigators, social workers or other peer supports represent clinical best practices for addressing the range of outcomes associated with toxic stress.

While mental health referrals are not recommended for all patients who have experienced ACEs, individuals who have trauma-related mental or behavioral health symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety, anger management concerns, and alcohol or other substance misuse or dependence) should be offered evidence-based and trauma-appropriate mental or behavioral health services.

“Addressing cultural competence, sensitivity, and humility must be an individual practice, as well as a priority for improving systems and policy more broadly,” Burke Harris’ report states.

Because Latino and Black populations are disproportionately burdened by barriers to access mental healthcare, extra efforts must be made to ensure equitable access to high-quality healthcare for vulnerable populations.

Additionally, after a referral, racial/ethnic minorities are much less likely to engage in mental health services. Outreach, integrated care, person-centered care, medical home models, culturally and linguistically congruent care, and peer support can improve engagement.

“California is advancing tertiary prevention of ACEs and toxic stress by providing up to $9 million through the California Initiative to Advance Precision Medicine to competitively fund three to five projects to demonstrate precision medicine approaches to addressing ACEs and toxic stress through research partnerships between academic centers and community or public health organizations,” according to a brief from the Office of the California Surgeon General.

What You Can Do to Address Toxic Stress

Share our Salud America! team’s 11-part exploration into the important recommendations in Dr. Nadine Burke Harris’ roadmap to address ACEs and toxic stress:

- Toxic Stress and its Lifelong Health Consequences. Toxic stress is a public health crisis that has lifelong impacts on physical, mental, and behavioral health.

- We Need to Recognize Toxic Stress as a Health Condition with Clinical Implications. Health experts are pushing to elevate toxic stress and developmental trauma on national research and policy agendas.

- Cut Toxic Stress with 3 Types of Public Health Prevention Interventions. Preventing toxic stress requires a three-level public health intervention approach.

- How to Use Healthcare Strategies to Address Toxic Stress. In clinics, hospitals, and other healthcare settings, workers can provide universal trauma-informed care and more. (current article)

- Using Public Health Strategies to Address Toxic Stress. When it comes to ACEs and resulting toxic stress, the public health sector can play a critical role by strengthening economic support, positive family relationships, and social services.

- How to Use Social Service Strategies to Address Toxic Stress. We need trauma-informed training for social workers, as well as family-friendly workplaces and home visits.

- Toxic Stress in Early Childhood and How to Prevent It. Early childhood is a key time for preventing ACEs and toxic stress.

- Toxic Stress in Justice and How to Address It. Encounters with police are “intrinsically stressful and potentially traumatic,” especially for youth of color.

- Toxic Stress in Education and How to Address It. ACEs and toxic stress can hinder a person’s learning and school success.

- California’s Epic Response to Toxic Stress and ACEs. California, already leading the nation in addressing ACEs, is making inroads to address toxic stress.

- 5 Upstream Ways You Can Take Action to Address Toxic Stress. Here are ways you can take action to address toxic stress.

Read the healthcare sector brief.

Share this with friends and colleagues in the healthcare setting.

Urge them and local leaders to raise awareness about the impacts of ACEs and toxic stress through a coordinated public education campaign.

Push for a robust toxic stress research agenda.

More research can help “identify clinically useful biomarkers to diagnose and follow risk of toxic stress longitudinally, as well as more specific therapeutic targets,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states.

“A key component of California’s strategy to reduce Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and toxic stress by half in a generation is the recognition of toxic stress as a health condition that is amenable to treatment and application of a rigorous scientific framework,” according to a brief from the Office of the California Surgeon General.

Explore More:

Healthy Families & SchoolsBy The Numbers

142

Percent

Expected rise in Latino cancer cases in coming years