Share On Social!

There is a common health condition with serious medical consequences that has not been nationally recognized by the medical or public health community—toxic stress response.

Toxic stress is the body’s response to prolonged trauma─like abuse or discrimination─with no support. It can harm lifelong mental, physical, and behavioral health, especially for Latinos and others of color.

But few, if any, clinical treatment guidelines have strategies for mitigating the toxic stress response.

That’s why Dr. Nadine Burke Harris’ Roadmap for Resilience: The California Surgeon General’s Report on Adverse Childhood Experiences, Toxic Stress, and Health wants California and others to recognize and respond to toxic stress as a health condition with clinical implications.

“We now understand that a key mechanism by which ACEs [adverse childhood experiences, such as exposure to violence] lead to increased health risks is through a health condition called the toxic stress response,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states.

Salud America! is exploring this as part of its 11-part series on toxic stress.

Common Health Conditions with Clinical Implications

Health experts know that exposure to certain substances in our environment, food, and consumer products─such as heavy metals, fine particulate matter, UVA rays, tobacco smoke, added sugar, and alcohol─can interfere with cellular and molecular functioning and result in health conditions with medical consequences or clinical implications.

This also applies to exposure to certain biological substances and physiological processes.

For example:

- Diabetes is a health condition where our pancreas doesn’t produce enough of the hormone insulin or when cells in our muscles, fat, and liver have become resistant to the hormone insulin, resulting in high blood sugar levels. This can lead to medical consequences, such as kidney failure, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, vision problems, foot problems, and heart disease.

- Alzheimer’s is a health condition thought to be caused by abnormal clusters of protein fragments that block communication among nerve cells causing cell death and tissue loss. It’s the destruction and death of these nerve cells that causes memory failure, personality changes, problems carrying out daily activities and other medical consequences.

- Thyroid disorders are health conditions where the thyroid produces too much or too little of the thyroid hormones, triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4), which can be caused by too little iodine or when the hypothalamus doesn’t produce enough thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) and/or when the pituitary gland doesn’t release enough thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). Too much or not enough of these thyroid hormones can lead to medical consequences, such as anxiety, irritability, fatigue, forgetfulness, weight loss, weight gain, irregular or frequent menstrual periods, vision problems, and sensitivity to hot or cold temperatures.

- Autoimmune diseases are health conditions where the immune system can’t tell the difference between your own cells and foreign cells, causing the body to attack normal healthy cells. For example, with Lupus, the immune system attacks joints, skin, organs, and the central nervous system, resulting medical consequences, such as blood clots, arthritis, kidney problems, lung problems, heart problems, headaches, organic brain syndrome, central nervous system vasculitis, and skin conditions.

Of course, there are many others.

Clinicians use two key resources to assess diseases, disorders, and conditions like those mentioned above: the American Psychiatric Association’s official Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM); and the World Health Organization’s International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD).

The DSM-5 serves as the authoritative guide to the diagnosis of mental disorders for clinicians and researchers in the United States and much of the world.

The ICD-11 defines the universe of diseases, disorders, injuries and other related health conditions and sets the global standard for all clinical and research purposes. It was recently updated in 2018, nearly 30 years after the 10th revision was released in 1990. The US still used the ICD-10.

However, there is no diagnostic entity or classification that describes the pervasive effects of toxic stress on child development and lifelong health.

Recognizing Toxic Stress is a Health Condition with Clinical Implications

A toxic stress response is a health condition where exposure to severe, intense, or prolonged stress, trauma, or adversity, such as child abuse and neglect, family incarceration, family mental illness, domestic violence, racism, and poverty, leads to the production of too much adrenaline and cortisol.

Too much of these stress hormones disrupts and changes neurological, endocrine, immune, metabolic and genetic regulatory functioning.

These changes can become “biologically embedded” whether the individual remembers the trauma or not and can contribute to social and medical consequences. For example:

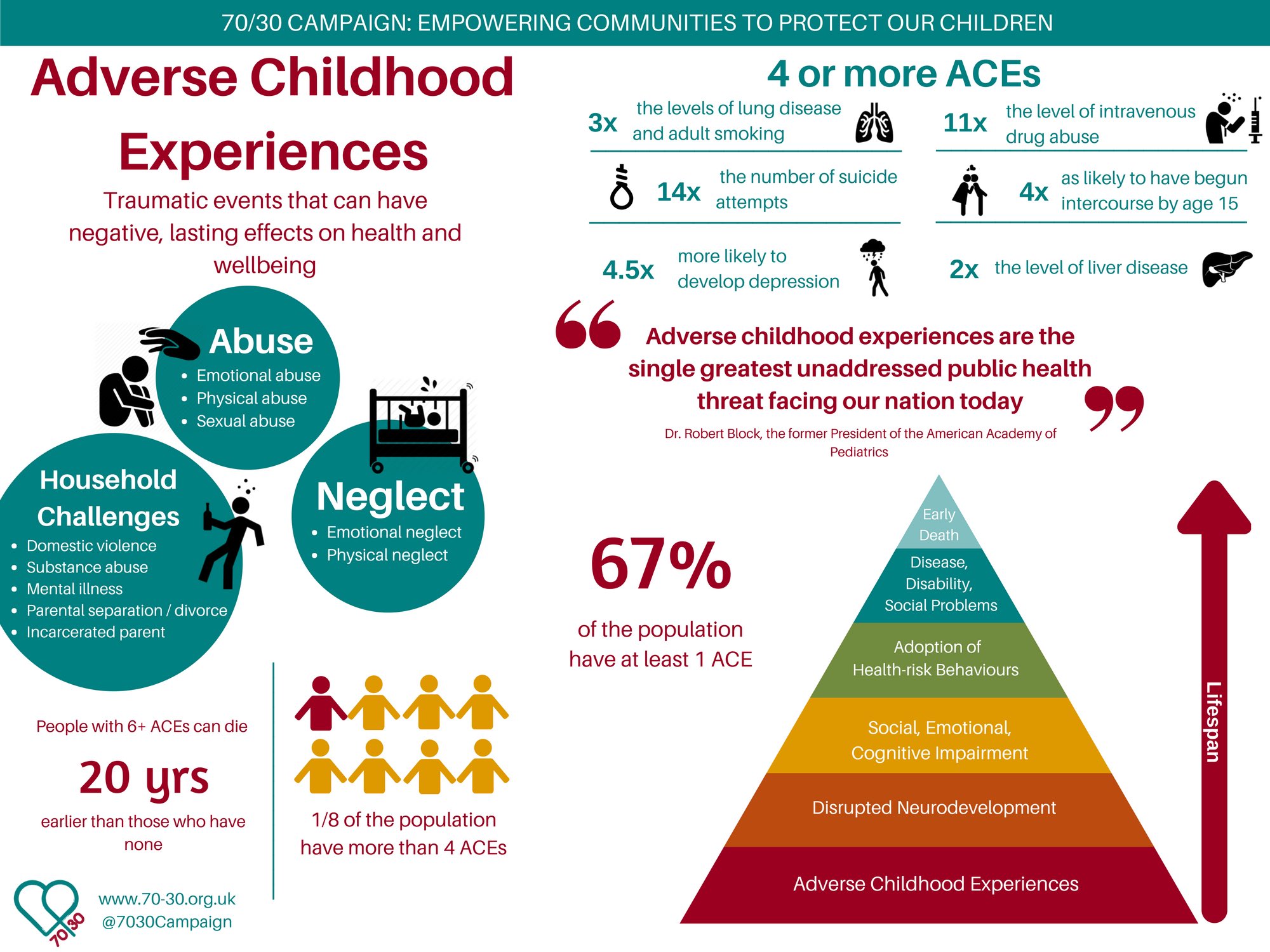

- Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are strongly associated with nine of the 10 leading causes of death: heart disease, cancer, accidents/unintentional injuries, chronic lower respiratory disease, stroke, Alzheimer’s disease or dementia, diabetes, kidney disease, and suicide attempts.

- ACEs are associated with our most pressing social problems, including learning, developmental, and behavior problems, dropping out of high school, unemployment, poverty, homelessness, and felony charges.

Many of these social problems contribute to the intergenerational transmission of adversity.

Ultimately, toxic stress response is a dysregulated stress response system—health condition.

And subsequent changes in biological and physiology that lead to lifelong mental, physical, and behavioral health problems—clinical implications.

And subsequent changes in biological and physiology that lead to lifelong mental, physical, and behavioral health problems—clinical implications.

However, toxic stress response is not nationally recognized as a health condition with clinical implications.

“Although the biological mechanisms of toxic stress are well supported by a consensus of scientific evidence, further research is necessary to determine whether the toxic stress response is best characterized as a condition, a disorder, or a disease,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states.

Moreover, in the absence of clinical diagnostic criteria, the combination of ACE score and the presence or absence of clinical implications, known as ACE-Associated Health Conditions (AAHCs), characterizing a patient as being at low, intermediate or high risk of manifesting a toxic stress response serves as proxy for the likely presence of a toxic stress response.

Yet toxic stress has not been included in the ICD-10.

Recognizing Developmental Trauma Disorder as a Health Condition with Clinical Implications, Too

Like toxic stress, Developmental Trauma Disorder is not nationally recognized as a health condition.

In 2005, Dr. Bessel A. van der Kolk constructed the diagnosis “Developmental Trauma Disorder” for the disruption to neurological, psychological, cognitive, and social functioning that occurs from trauma by caregivers during critical development periods in the early years of life.

“Chronic trauma interferes with neurobiological development and the capacity to integrate sensory, emotional and cognitive information into a cohesive whole,” according to van der Kolk. “Developmental trauma sets the stage for unfocused responses to subsequent stress, leading to dramatic increases in the use of medical, correctional, social and mental health services.”

In the absence of clinical diagnostic criteria, Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and other overlapping disorders are often used—inadequately—for Developmental Trauma Disorder.

Many even make a PTSD diagnosis, which is for adult-onset trauma, for children.

This is problematic for many reasons, particularly because many ACEs do not qualify for a PTSD diagnosis.

“Interestingly, many forms of interpersonal trauma, in particular psychological maltreatment, neglect, separation from caregivers, traumatic loss, and inappropriate sexual behavior, do not necessarily meet DSM-5 ‘Criterion A’ definition for a traumatic event,” according to van der Kolk.

That’s why, in 2009, with the Complex Trauma taskforce of the National Child Traumatic Stress Network, van der Kolk proposed Developmental Trauma Disorder to the DSM Trauma, PTSD, and Dissociative Disorders Subwork Group to be included in the DSM-5.

The goal was to make the distinction from PTSD in adults as well as from other overlapping disorders and to provide a classification for children that addresses the consistent and predictable consequences that a dysregulated stress response has on many areas of development, functioning, and behavior.

“The diagnosis of PTSD is not developmentally sensitive and does not adequately describe the effect of exposure to childhood trauma on the developing child,” according to van der Kolk. “Moreover, the PTSD diagnosis does not capture the developmental effects of childhood trauma:

- the complex disruptions of affect regulation;

- the disturbed attachment patterns;

- the rapid behavioral regressions and shifts in emotional states;

- the loss of autonomous strivings;

- the aggressive behavior against self and others;

- the failure to achieve developmental competencies;

- the loss of bodily regulation in the areas of sleep, food, and self-care;

- the altered schemas of the world;

- the anticipatory behavior and traumatic expectations;

- the multiple somatic problems, from gastrointestinal distress to headaches;

- the apparent lack of awareness of danger and resulting self-endangering behaviors;

- the self-hatred and self-blame; and

- the chronic feelings of ineffectiveness.”

However, Developmental Trauma Disorder was not included in the DSM-5 due to lack of evidence, according to a blog by Mary Sykes Wylie. Developmental Trauma Disorder was also not included in the 2018 IDC-11.

“[Developmental Trauma Disorder’s] comorbidities overlap with but extend beyond those of PTSD to include panic, separation anxiety, and disruptive behavior disorders,” according to a 2019 study. “[Developmental Trauma Disorder] warrants further investigation as a potential diagnosis or a complex variant of PTSD in children.”

Therein lies the “catch-22” of not recognizing toxic stress and Development Trauma Disorder in the DSM-5 and ICD-10—without recognition, these issues don’t receive adequate funding for investigation/research, and without adequate research, these issues don’t get recognized.

Therein lies the “catch-22” of not recognizing toxic stress and Development Trauma Disorder in the DSM-5 and ICD-10—without recognition, these issues don’t receive adequate funding for investigation/research, and without adequate research, these issues don’t get recognized.

For example, “for the first time, WHO is classifying gaming disorder as an addictive behavior disorder – now we can measure how many people are affected,” according to a WHO infographic.

Today, neither toxic stress nor Development Trauma Disorder are in the ICD-10 or the DSM-5, which means we aren’t measuring how many people are affected.

Responding to Toxic Stress as a Health Condition with Clinical Implications

Burke Harris and her roadmap want to recognize and respond to toxic stress as a health condition with clinical implications.

She knows that like any other health condition, addressing toxic stress will require a public health approach to prevention, early detection, and early intervention.

Many other experts agree. Some have even testified to Congress, like Dr. Christina Bethell with the Department of Population, Family and Reproductive Health at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

“While the term ‘toxic stress’ was originally coined by the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child to describe the developmental changes associated with prolonged adversity in a policy context, it is now recognized that the accumulated changes to the physiologic stress response system, as well as brain and other organ system development, represent a health condition with clinical implications,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states.

Recognizing toxic stress as a health condition is particularly important amid COVID-19.

The toxic stress response increases the burden of ACE-Associated Health Conditions (AAHCs) such as heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease and obesity, which increase risk of a more severe COVID-19 disease and death. Latinos are suffering a heavy burden of coronavirus cases and deaths.

“The biological condition of being stress-sensitized also increases the risk of stress-related chronic disease exacerbations associated with living through the pandemic,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states. “These health and social impacts particularly affect those with higher baseline vulnerability, including individuals with a history of adversity, those with lower incomes and education, those more vulnerable to job loss, housing insecurity, food insecurity, and poverty, as well as those with underlying chronic health conditions, disabilities, and older age.”

Many other trauma-informed advocates across the country are working to respond to ACEs and toxic stress, particularly amid the pandemic.

For example, the Campaign for Trauma-Informed Policy and Practice (CTIPP), released a policy brief suggesting a trauma-informed agenda for the first 100 days of the Biden-Harris Administration.

The policy brief provides short term priorities to address the psycho-social-emotional impact of the pandemic as well as short term priorities to address ACEs and toxic stress.

Priorities include establishing a goal of preventing ACEs and reducing their impact by 50% by 2030, as well as:

- Secondary and vicarious trauma: Recipients of funds in any new stimulus bill should be advised on how they can use those funds to provide trauma-informed and resilience strategies for those most at-risk for secondary/vicarious trauma, such as teachers, law enforcement officers, first responders, nurses and other healthcare workers, mental health and social welfare workers and others serving people and communities affected by the pandemic.

- Racial, intergenerational, and historical trauma: Increase representation of marginalized communities in shaping public policy and engage them in translating policy in local community action, particularly Latino and other communities of color, indigenous communities, LGBTQIA+ communities, and others have suffered throughout the history of our country.

- National healing campaign: Move the Interagency Task Force on Trauma-Informed Care from HHS to the White House and expand its responsibilities to develop a comprehensive plan to reach this goal of reducing ACEs by 2030. Prioritize approaches to serve marginalized communities suffering high levels of ACEs, diseases of despair, and associated health conditions

- Federal trauma-informed and anti-racism training: Require online trauma-informed and anti-racism trainings for all federal employees engaged in human services programs, with extra emphasis on reaching those in policy making positions.

- Addressing trauma at the border: Reallocate funds from the Border Wall and use it to provide trauma-informed services to promote healing among the families who suffer trauma as a result of family separation and other Border policies.

In January, 20201, the International Transformational Resilience Coalition (ITRC), released the ITRC Mental Wellness and Resilience Policy calling for a public health prevention approach to preventing and healing toxic stress generated by the climate emergency.

The ITRC policy calls on Congress to enact and fund the Mental Wellness and Resilience Act (MWRA) to make the prevention of mental health and psychosocial problems a national priority and calls on the establishment of an Office of Mental Wellness and Resilience in the Department of Health and Human Services.

Momentum for policy action was building even before these recent reports.

Between Spring 2013 and Winter 2017, more than 500 individuals were involved in a field-building and agenda-setting process to advance improvements in child and family well-being by addressing ACEs.

They developed an applied child health services national agenda to address ACEs with four overarching priorities, four research areas, and 16 short-term actions leverage existing policies, practices, and structures to advance agenda priorities and research priorities.

The four overarching priorities are to:

- translate the science of ACEs, resilience, and nurturing relationships into children’s health services;

- cultivate the conditions for cross-sector collaboration to incentivize action and address structural inequalities;

- restore and reward for promoting safe and nurturing relationships and full engagement of individuals, families, and communities to heal trauma, promote resilience, and prevent ACEs; and

- fuel “launch and learn” research, innovation, and implementation efforts.

The four research areas are related to:

- family-centered clinical protocols

- assessing effects on outcomes and costs

- capacity-building and accountability

- role of provider self-care to quality of care

The 16 actions from the initiative include:

- Prioritize early and periodic screening, diagnostic and treatment, and prevention

- Focus hospital community benefits strategies

- Establish enabling organization, payment, and performance measurement policies

- Advance and test Medicaid policy implementation

- Inform and track legislation to accelerate translation

- Leverage medical/health home and social determinants of health “movement”

- Enable, activate, and support child, youth, and family engagement

- Build effective peer/family to peer/family support capacity

- Empower community-based services and resource brokers (eg, early childhood programs like Head Start, Help Me Grow, Healthy Start, Healthy Steps, school health, youth, and after school programs)

- Leverage Existing Research and Data Platforms, Resources, and Opportunities

- Optimize existing federal surveys and data

- Optimize state surveys

- Liberate available data

- Build crowdsourcing, citizen science, and N of 1 methods

- Integrate common-elements research modules for longitudinal studies

- Link to collaborative learning and research networks

“Efforts to address the high prevalence and negative effects of ACEs on child health are needed, including widespread and concrete understanding and strategies to promote awareness, resilience, and safe, stable, nurturing relationships as foundational to healthy child development and sustainable well-being throughout life,” according to a 2017 summary about the four-year agenda-setting initiative published in the Journal of the Academic Pediatric Association.

What You Can Do to Address Toxic Stress

Share our Salud America! team’s 11-part exploration into the important recommendations in Dr. Nadine Burke Harris’ roadmap to address ACEs and toxic stress:

- Toxic Stress and its Lifelong Health Consequences. Toxic stress is a public health crisis that has lifelong impacts on physical, mental, and behavioral health.

- We Need to Recognize Toxic Stress as a Health Condition with Clinical Implications. Health experts are pushing to elevate toxic stress and developmental trauma on national research and policy agendas. (current article)

- Cut Toxic Stress with 3 Types of Public Health Prevention Interventions. Preventing toxic stress requires a three-level public health intervention approach.

- How to Use Healthcare Strategies to Address Toxic Stress. In clinics, hospitals, and other healthcare settings, workers can provide universal trauma-informed care and more.

- Using Public Health Strategies to Address Toxic Stress. When it comes to ACEs and resulting toxic stress, the public health sector can play a critical role by strengthening economic support, positive family relationships, and social services.

- How to Use Social Service Strategies to Address Toxic Stress. We need trauma-informed training for social workers, as well as family-friendly workplaces and home visits.

- Toxic Stress in Early Childhood and How to Prevent It. Early childhood is a key time for preventing ACEs and toxic stress.

- Toxic Stress in Justice and How to Address It. Encounters with police are “intrinsically stressful and potentially traumatic,” especially for youth of color.

- Toxic Stress in Education and How to Address It. ACEs and toxic stress can hinder a person’s learning and school success.

- California’s Epic Response to Toxic Stress and ACEs. California, already leading the nation in addressing ACEs, is making inroads to address toxic stress.

- 5 Upstream Ways You Can Take Action to Address Toxic Stress. Here are ways you can take action to address toxic stress.

Share this with friends and colleagues to raise awareness about toxic stress.

Urge local leaders to recognize and respond to toxic stress as a health condition that can be prevented and mitigated.

Push for a robust toxic stress research agenda.

More research can help “identify clinically useful biomarkers to diagnose and follow risk of toxic stress longitudinally, as well as more specific therapeutic targets,” Burke Harris’ roadmap states.

“A key component of California’s strategy to reduce Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and toxic stress by half in a generation is the recognition of toxic stress as a health condition that is amenable to treatment and application of a rigorous scientific framework,” according to a brief from the Office of the California Surgeon General.

By The Numbers

142

Percent

Expected rise in Latino cancer cases in coming years