Share On Social!

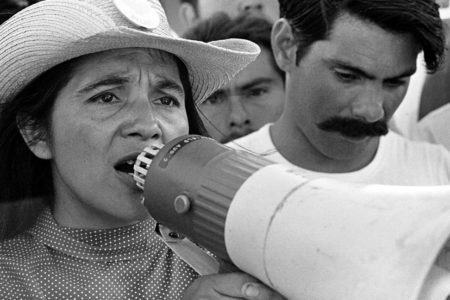

Dolores Huerta taught us sí se puede—yes we can.

This was Huerta’s rallying cry as she inspired Latino farm workers to demand fair wages and better working conditions in the 1970s.

In the decades after she co-founded the United Farm Worker’s Union with César E. Chávez and made many gains for workers, she has continued to serve as a powerful voice to develop leaders and advocate for the Latino working poor, women, and children.

Huerta, now 91, “travels across the country engaging in campaigns and influencing legislation that supports equality” and “speaks to students and organizations about issues of social justice and public policy,” according to the Dolores Huerta Foundation.

“A lot of people don’t realize that they actually can make a difference. That’s what we have to do when we’re organizing, make them understand that not only do they have that right, but they have that responsibility and that we need them,” Huerta told Glamour.

For Hispanic Heritage Month, we at Salud America! honor the life and legacy of Huerta.

Huerta and Her Early Life and Path Toward Civil Rights Action

Dolores Clara Fernández Huerta was born on April 10, 1930, in Dawson, a small mining town in the mountains of northern New Mexico. She spent most of her childhood and early adult life in Stockton, California where she and her two brothers moved with their mother, following her parents’ divorce.

Her grandparents were Mexican migrants.

Huerta’s mother, Alicia, participated in community affairs, civic organizations and the church. Her mother’s community activism was reflected in Dolores’ involvement as a student at Stockton High School.

Dolores excelled at organization and detail. She believed in tackling issues head-on and comfortably handled many confrontations.

While serving in the leadership of the Stockton Community Service Organization (CSO), she founded the Agricultural Workers Association, set up voter registration drives, and pressed local governments for barrio improvements.

Later in 1962, she resigned from CSO and launched the National Farm Workers Association, a forerunner of the United Farm Workers (UFW), with her colleague CSO Executive Director César E. Chávez. This helped her become an important catalyst in the enactment of the Agricultural Labor Relations Act of 1975, the first law of its kind in the United States, granting farm workers in California the right to collectively organize and bargain for better wages and working conditions.

“Sí se puede is a term rooted in the struggle of working-class Latinos. It was the rallying cry of the United Farm Worker’s Union in the 1970s. Co-founders Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez adopted the motto during a 25-day fast in Phoenix, Arizona where they were trying to organize farm workers to demand fair wages and better working conditions. This mantra was meant to galvanize workers and inspire them. Yes, we can start a movement against all odds. Yes, we can stand up against exploitation. Yes, we can fight for fair wages and medical and pension benefits. Over the years, “Sí se puede” has also been adopted by other civil and labor rights groups involving Latinos around the country,” according to American Progress.

In the 1980s, Huerta co-founded UFW’s radio station. She continued to speak and raise funds on behalf of a variety of causes, including farm laborers’ health.

From 1988 to 1993, Huerta served on the U.S. Commission on Agricultural Workers, established by Congress to evaluate special worker provisions and labor markets in the agriculture industry.

Huerta has been arrested over 20 times, often hee product of civil disobedience non-violent acts such as boycotts or strikes.

“Throughout the 1970s and ‘80s, Huerta worked as a lobbyist to improve workers’ legislative representation,” according to the National Women’s History Museum.

Huerta Takes the Cause Forward to Civil Rights

In 2002, Huerta founded the Dolores Huerta Foundation (DHF).

The group is involved in community organizing at the grassroots level, engaging and developing natural leaders.

“Our social justice grassroots organizing work is focused on Education, Health and Safety, LGBTQIA+, Equality and Civic Engagement,” according to the foundation. “[The Foundation] is committed to dismantling the school-to-prison pipeline through student and parent training for meaningful engagement and advocacy.”

Huerta also has worked to elect several candidates over the years.

These include President Clinton, Congressman Ron Dellums, Governor Jerry Brown, Congresswoman Hilda Solis, and Hillary Clinton-Women’s Liberation.

“During the 1990s and 2000s, she worked to elect more Latinos and women to political office and has championed women’s issues,” according to the National Women’s History Museum.

Huerta and Her Recognition and Legacy

Huerta has received numerous awards.

These include: The Eleanor Roosevelt Humans Rights Award from President Clinton in 1998, Ms. Magazine’s One of the Three Most Important Women of l997, Ladies Home Journal’s 100 Most Important Women of the 20th Century, The Puffin Foundation’s Award for Creative Citizenship.

In 2012, President Obama bestowed Huerta with The Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award in the United States.

“The freedom of association means that people can come together in an organization to fight for solutions to the problems they confront in their communities. The great social justice changes in our country have happened when people came together, organized, and took direct action. It is this right that sustains and nurtures our democracy today. The civil rights movement, the labor movement, the women’s movement, and the equality movement for our LGBT brothers and sisters are all manifestations of these rights. I thank President Obama for raising the importance of organizing to the highest level of merit and honor,” Huerta said at the time, according to her Foundation website.

In 2017, “Peter Bratt (director) and Carlos Santana (producer) tell her story in the new documentary Dolores, finally giving her the rightful place in history she deserves,” Bioneers reports.

Huerta’s strength and personality undoubtedly helped many Latinos.

“I have to say this that when it comes to racism, I will call people out immediately, even though it embarrasses them. In front of people, because I want them to feel the pain, embarrassment. I call it an instant education,” Huerta told Glamour.

How Can You Help Latinos Fight for Health Equity?

We can do our part to fight for health equity for Latinos and other people in your area.

Get a “Health Equity Report Card” for Your Area!

Select your county name and get a customized Health Equity Report Card by Salud America! at UT Health San Antonio. You will see how your area stacks up in housing, transit, poverty, health care, healthy food, and other health equity issues. These compare to the rest of your state and nation.

You can email your Health Equity Report Card, share it on social media, and use it to make a case for community change.

“Share an interactive version of your local Health Equity Report Card to make the case to address existing inequities and strengthen your community’s ability to respond to and recover from disasters so everyone has a fair opportunity to live their healthiest lives possible,” said Dr. Amelie G. Ramirez, director of the Salud America! Latino health equity program, funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and based at the Institute for Health Promotion Research in the Department of Population Health Sciences at UT Health San Antonio.

Get your Health Equity Report Card!

Editor’s Note: Main image via Bioneers and the documentary film “Dolores.”

By The Numbers

44

million

immigrants live in the United States

This success story was produced by Salud America! with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The stories are intended for educational and informative purposes. References to specific policymakers, individuals, schools, policies, or companies have been included solely to advance these purposes and do not constitute an endorsement, sponsorship, or recommendation. Stories are based on and told by real community members and are the opinions and views of the individuals whose stories are told. Organization and activities described were not supported by Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and do not necessarily represent the views of Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.