Share On Social!

Researchers have recently discovered 65 genetic variants in minority populations, which could lead to improved specialized medicines for those groups.

Up to this point, doctors have conducted the majority of medical discovery research using data from people with European ancestry, according to the international science journal, Nature — leading to a lack of diversity that hinders precision medicine for minority populations.

The news is excellent for Latinos and all minorities who have traditionally been understudied or left out of clinical research.

“This is an extremely important public health issue,” Misa Graff, assistant professor in the school’s epidemiology department and co-author of the paper told UNC News.

“We need to work hard to make sure that the populations most burdened by disease are not overlooked by genomic studies, because we cannot afford for disease disparities to get worse. Understanding the genes in these populations is key to targeting prevention and designing drugs that can better target their illnesses and improve quality of life.”

What is Precision Medicine?

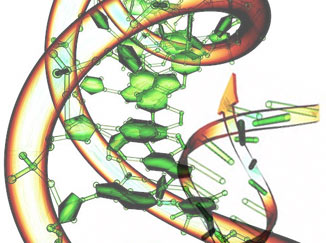

This method is “an emerging approach for disease treatment and prevention that takes into account individual variability in genes, environment, and lifestyle for each person,” according to the U.S. National Library of Medicine (NLM).

Precision medicine permits physicians and researchers to predict more accurately which treatment and prevention strategies for a specific disease will work in which groups of people.

Ethnic groups are unique, as are their genetics. Using a blanketed approach in medicine for all groups is not as effective as honing in on individual traits.

NLM goes on to state, while this is an emerging field, the concept is not new. They cite matching blood types for transfusions as an example.

What Does the Study Show?

The “Population Architecture using Genomics and Epidemiology” (PAGE) study, investigated links between genes and sicknesses among different ethnicities in the U.S.

Scientists from institutions all over the U.S. investigated “phenotypes of nearly 50,000 non-European individuals, identifying 65 new associations and replicating 1,400 associations between genes and diseases, emphasizing the need for equitable inclusion of diverse populations in genetic research.”

These are previously undiscovered points along chromosomes where genetic variants are located, but that have not been found already in European populations. However, they are likely to be transmittable to other demographics that share a common ancestry, such as African origin among Latinos and Blacks.

For example, a sickle cell variant gene is found in some Latino populations with African ancestry. The irregularity can cause inaccurate glucose level readings, which can result in 2 diabetes patients to think or that their glucose is under control when, in fact, it is not.

“It is important that we no longer make assumptions based on what someone looks like or their perceived race – which is an inappropriate biological construct – and project what they might be at risk for or whether their disease is under good control,” said Kari North, a professor in the epidemiology department at the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health and co-author of the study.

Why Does This Matter?

Bias in research and healthcare can lead to false assumptions and adverse health outcomes.

While the Latino population is continuously rising, Latinos and other minorities are still profoundly underrepresented in the healthcare workforce as well as clinical research.

With different genetic makeups, members of minority groups, including Latinos and blacks, may react to treatment differently.

Additionally, with continued population growth, genes are continuously mixing.

This means diversifying research is increasingly important as well as understanding how genes are affected by socioeconomic and environmental factors.

“An important step in genetic medicine is determining how often a genetic variant occurs in healthy people. If a variant is common in the wider population, it is unlikely to be harmful, but in most of our databases that ‘wider population’ is comprised mostly of European ancestry,” said North.

“Unless we increase our efforts to study diverse populations, we are going to continue to make these mistakes.”

Explore More:

Overcoming Harmful BiasesBy The Numbers

3

Big Excuses

people use to justify discriminatory behavior