Share On Social!

Police came to four-year-old Fatimah Muhammad’s house in Newark, N.J. (34% Latino), after an altercation between her parents.

They came in with force. They had guns.

They aggressively grabbed and body-slammed her father before taking him away, Muhammad said.

“I was completely terrified,” she said. “Instead of feeling grateful.”

As a kid, Muhammad didn’t have a name for some of the traumas that she and her neighborhood were experiencing, like police aggression, domestic violence, and mass incarceration.

But she felt an “us vs. them” sense when it came to police.

Years later, amid a wave of unlawful policing in Newark, Muhammad helped seize an opportunity to unite police and community to explore trauma and rebuild trust.

Update 6/2/20: Muhammad is currently Executive Director at the Health Alliance for Violence Intervention.

‘Unconstitutional’ Law Enforcement

Over the years, tensions mounted between police and people in Newark.

Since the war on drugs in the 1980s, mass incarceration became the engine driving law enforcement. That arrived on the heels of civil rights activities being met with police force.

“Drugs were everywhere and the response to that was aggressive policing,” said Muhammad, who joined Equal justice USA, a national organization that works to transform the justice system by promoting responses to violence that break cycles of trauma, in 2015.

In 2011, New Jersey’s American Civil Liberties Union filed a misconduct complaint against the Newark Police Department.

A three-year investigation by the Department of Justice found a “pattern and practice of unconstitutional policing.”

Similar investigations occurred across the country.

Unconstitutional policing was so rampant, that police departments needed federal judges and moderators to go through policy by policy and practice by practice.

“Our investigation uncovered troubling patterns in stops, arrests and use of force by the police in Newark,” Attorney General Eric Holder said in a statement.

Meanwhile, President Barak Obama issued an Executive Order appointing an 11-member task force on 21st century policing to respond to a number of serious incident between law enforcement and the communities they serve and protect.

In 2015, the task force released the Final Report of The President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing.

In 2015, the task force released the Final Report of The President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing.

In 2016, Newark city leaders signed a consent decree, agreeing to change unlawful policies and practices.

With Equal Justice USA, Muhammad was invited to be part of those conversations and to help rebuild community trust.

“The history of policing is so connected to slave-catchers in the south and this whole lineage of tension that hasn’t really been addressed,” Muhammad said.

If we want to rebuild community trust, the whole system must change, Muhammad said.

This was an opportunity to change the system and re-define what it means to be a Newark police officer in the 21st century.

Muhammad thinks it is someone who understands trauma, procedural justice, and the history of and dynamics in the community.

Someone like Donna Roman Hernandez.

Wellness/Culture of Law Enforcement

Hernandez served as a law enforcement officer for 30 years before retiring as police captain at Caldwell Police Department.

When she started there, she was the first female officer and the first Latino officer.

It was both rewarding and noble, but also a long journey with tribulations and divisiveness, she said.

Officers were not given mental or emotional support to deal with the traumas they see day in and day out for years and years, like seeing their colleagues get shot or experience domestic violence, which Hernandez has seen and experienced.

“I was strangled nearly to death, but I didn’t have anyone to talk to because it is frowned upon for cops to be weak,” Hernandez said.

Officers put their lives on the line every day, but the stigma of mental health is so bad that they don’t get the care they need. Police officers die from suicide 2.4 times as often as from homicides, according to the Final Report. Also, poor nutrition, lack of physical activity, sleep deprivation and substance use disorder account for a large proportion of officer injuries and deaths.

“An officer whose capabilities, judgment, and behavior are adversely affected by poor physical or psychological health not only may be of little use to the community he or she serves but also may be a danger to the community and to other officers,” according to the Final Report.

“Though depression resulting from traumatic experiences is often the cause, routine work and life stressors—serving hostile communities, working long shifts, lack of family or departmental support—are frequent motivators too.”

Growing up in Newark, Hernandez faced physical violence and emotional terrorism at the hands of her father. In 2009, she released a documentary about her trauma, The Ultimate Betrayal: A Survivor’s Journey.

So when Hernandez got an email from Muhammad asking for help with a new project to build trust between law enforcement and community members through trauma-informed training in Newark, Hernandez was eager to help.

Addressing Trauma in Newark

Muhammad asked Hernandez a lot of questions about what police offers are like on and off the job and the types of training and resources they receive.

“I was able to express my feelings and tell her some things I did not like about law enforcement,” Hernandez said.

“It’s OK to cry. It’s OK to take it home and think about it,” Hernandez said. “What’s not OK is to hold on to it and feel alone and take it out on the community.”

They both wanted to address that issue.

With help from other partners, like Safer Newark Council, they hosted community meetings to bring police officers and community members together to come up with a vision for the project.

Trauma came up a lot.

“When you live in a community where you see violence, there is also joy, music and dancing,” Muhammad said. “You don’t know where the trauma begins and where the everyday neighborhood ends.”

Like the rest of the nation, Newark was facing police aggression, the opioid crisis, the mental health crisis and high suicide rates among officers.

In Newark, young Latin men are 15 times more likely to be victims of homicide than white males and African Americans males 19 times more likely.

Offers admitted feeling blamed for problems in other departments and police aggression happening across the country.

“Officers needed to hear from other officers,” Hernandez said.

The community needed to hear from officers, too.

The community was reminded that people uniform are also human beings and they work in systems that are not set up to help them do their job well.

Officers were reminded that young children are often present and witness aggression.

“Through the lens of trauma you see that we are more alike than we are different,” Muhammad said.

Both sides wanted to do this again. They wanted more understanding of trauma and issues of race. They wanted skills to recognize and deal with trauma.

“Community-level healing requires facilitation,” Muhammad said.

As a piece of the larger reformation of the Newark Police Department, Muhammad wanted to create a trauma-informed training curriculum and looked to public health interventions and programs.

Using Public Health Approach to Violence Prevention

Even before starting a trauma-informed training program, wheels of change were turning.

Newark Mayor Ras J. Baraka was already leading the way to develop public health responses to violence and elevate the importance of being trauma-informed.

“I got so excited personally about a leader who has a vision and innovative people on the group addressing public safety issues through a public health lens,” Muhammad said.

62% of murders in Newark were relationship-based, according to a video.

“Exposure to violence makes you more likely to perpetrate harm or be a victim of harm,” Muhammad said.

It’s infectious.

Like a cold, you need credible people in the community to intervene or interrupt it before it starts.

The mayor launched the Newark Community Street Team, to employ residents and non-traditional leaders as credible messengers. They serve as interventionists, mentors and outreach workers. They even help ensure kids get to and from school safely.

In 2016, there was a 12% reduction in homicides.

“Law enforcement contacts for apparent infractions create trauma and fear in children and disillusionment in youth, but proactive and positive youth interactions with police create the opportunity for coaching, mentoring, and diversion into constructive alternative activities,” according to the Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing.

Trauma-Informed Training in Newark

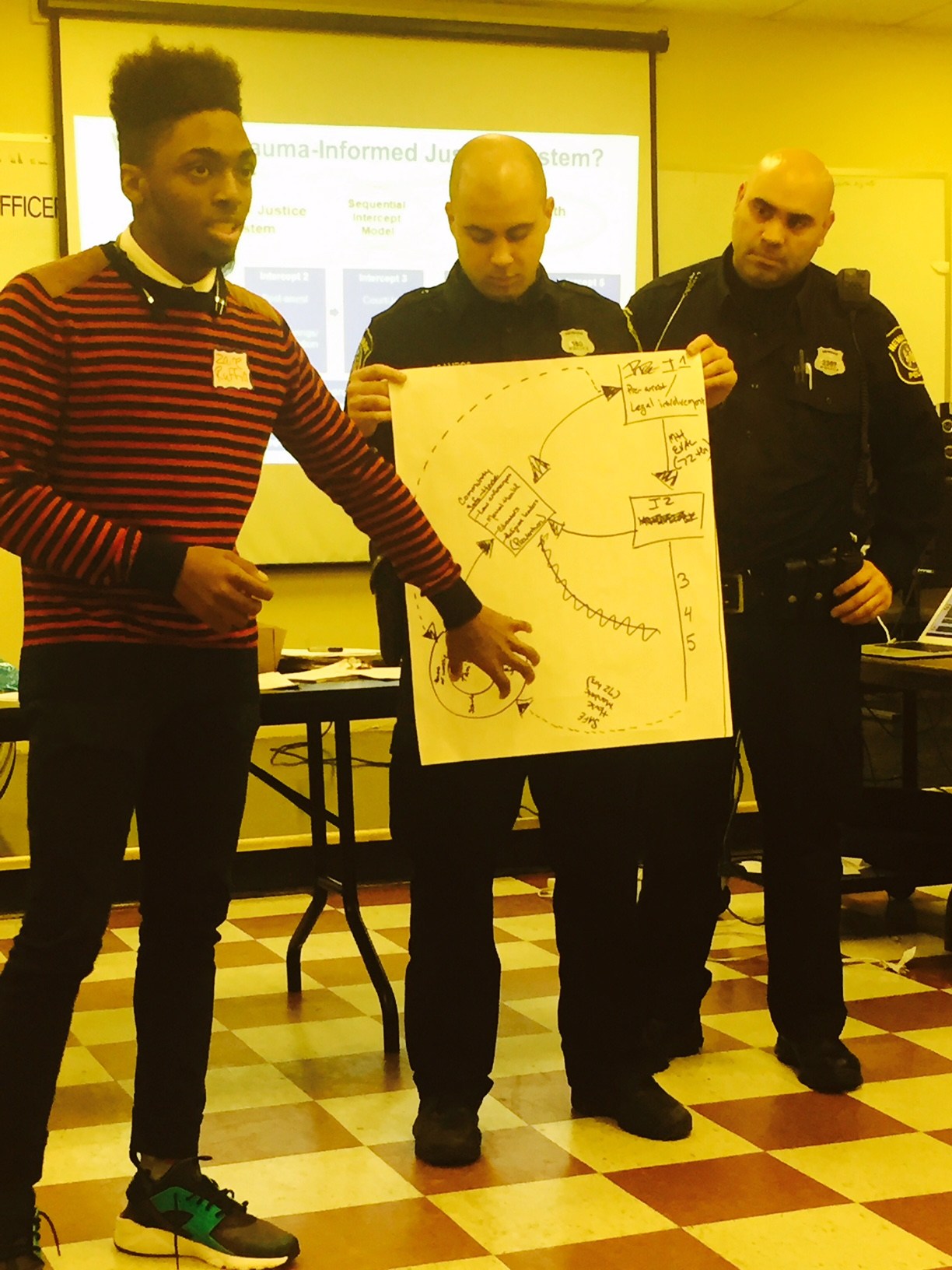

In this environment and aided by Hernandez and others, Muhammad and Equal Justice USA launched a pilot program in 2016 to teach Newark police and civilians on how trauma impacts their daily lives.

The program—Police/Community Initiative on Trauma-Informed Responses to Violence—brings together police officers, community leaders, healthcare providers, and violence interrupters for honest conversations about trauma and violence.

Participants meet several times over a month for 4-hour discussions.

They watch videos, work in teams, and have real discussions. They talk about how trauma impairs early childhood development and increases risk for truancy, dropping out of high school, substance use disorder, and other risky behaviors.

Equal Justice USA’s program tries to ensure that:

- trauma survivors and witnesses have adequate resources and support in the wake of violence;

- police officers have skills to de-escalate and support those in need; and

- officers who experience what is known as secondary or vicarious trauma can adopt healthy practices for themselves.

“In my [Newark police] officers, I see a desire to recognize the trauma in the community and to use that understanding to work together to reduce violence and help the victims. They really believe now that as a city we can get away from the ‘US vs THEM’ mentality. The community has been saying this for years. We, as a department, weren’t listening. We thought we knew it all – and that good policing was arresting the bad guys and being the warriors. Now we are listening. Now we understand that we are guardians of the community and we need to understand the root of the problem and be part of the solution,” said Newark Police Lt. Louis Forst, on the Equal Justice USA website.

Equal Justice USA program trained more than 300 police officers and civilians through their Police-Community Trauma Program.

Equal Justice USA program trained more than 300 police officers and civilians through their Police-Community Trauma Program.

“They are going to change lives and change the way people look at police and change the way the police looks at the community,” Hernandez said.

Since the program, there has been a 50% reduction of civilian complaints of officers.

“Difficult at first, these dialogues become transformative when both sides understand that is it the system itself that harms them,” Muhammad said. “From there, they are ready to organize together and create powerful change. I’ve seen it over and over again. It moves me every time.”

In March 2018, EJ USA hosted a national convening to build a national network of people impacted by trauma across the criminal justice system.

Watch a video to learn about how schools are working with police in San Antonio to support students who experience trauma through the Handle With Care program.

What Can You Do?

Over 65 cities have started Handle With Care.

You can get Handle With Care started in your community, too!

Download the free Salud America! “Handle With Care Action Pack” to start a Handle With Care program, in which police notify schools when they encounter children at a traumatic scene, so schools can provide support right away.

The Action Pack, which contains materials and technical assistance to help school and police leaders everywhere plan their own Handle With Care program, was created by Dr. Amelie G. Ramirez, director of the Salud America! Latino health equity program at UT Health San Antonio, with help from the West Virginia Center for Children’s Justice, which started the Handle With Care program in 2013.

By The Numbers

28

percent

of Latino kids suffer four or more adverse childhood experiences (ACES).

This success story was produced by Salud America! with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The stories are intended for educational and informative purposes. References to specific policymakers, individuals, schools, policies, or companies have been included solely to advance these purposes and do not constitute an endorsement, sponsorship, or recommendation. Stories are based on and told by real community members and are the opinions and views of the individuals whose stories are told. Organization and activities described were not supported by Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and do not necessarily represent the views of Salud America! or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.