Share On Social!

Latino and black children are more likely to die of numerous childhood cancers than their white counterparts, NPR reports on a new study in the journal Cancer.

Latinos also are more likely to receive a cancer diagnoses in later, less curable cancer stages.

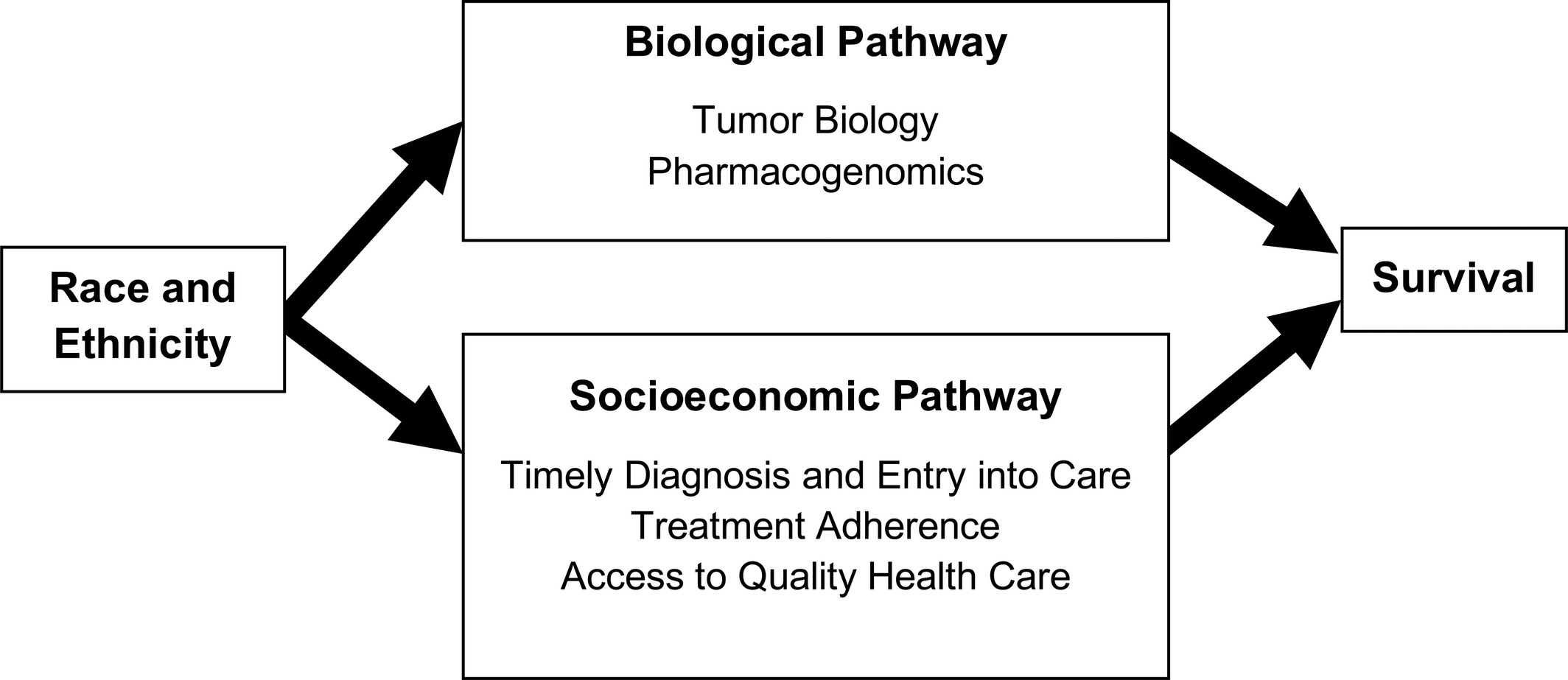

Socioeconomic status plays an enormous role in childhood cancer survival as well. Latino and black children are more likely to live in areas of poverty, which subjects them to persistent racism and institutional bias.

“We know that there are some economic differences that are closely tied to race and ethnicity,” Rebecca Kehm, lead author of the study, told NPR. “I wanted to show that there are other factors at play than the genetic component.”

The Study: Social Class & Disparities

Cancer is the leading cause of death among Latinos in the United States.

That isn’t changing anytime soon. In fact, Latinos are expected to face 142% rise in cancer in the coming years.

So Kehm and her team at the University of Minnesota used the NIH’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER), a database of cancer statistics composed of 19 geographic areas in the US, to analyze data on 32,000 childhood cancer patients.

The SEER data shows a snapshot of each individual patient diagnosed between 2000 and 2012, and includes their race and where they live.

The new research confirmed what they already knew: race does greatly affect a child’s likelihood of surviving cancer.

Black children were between 38-95% percent more likely than whites to die of the nine cancers researchers looked at.

Latinos children were between 31-65% more likely to die.

In almost half of the types of cancer cases examined, poverty and other socioeconomic issues appeared to exemplify the racial disparities for numerous cancers. These included acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), neuroblastoma, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. A prime example is a black child who is diagnosed with ALL is 43% more likely to die than a white child with ALL.

Dr. Karen Winkfield, a radiation oncologist and director of Wake Forest Baptist Health’s Office of Cancer Health Equity told NPR that the results are not surprising, and that studies like this one put focus on people who can’t speak for themselves.

“There are children who die who should not die because their parents are poor,” she stated to NPR. “What does this say about our society?”

Other Risks, Solutions

We already know that children in poverty have a greater cancer risk.

Latino kids and those with a lower socioeconomic status are exposed to more pollution—and thus diabetes—than their affluent counterparts. Latino children also face unhealthy school environments, a lack of access to disease-fighting healthy food and drinks, and a lack of access to safe places to play and exercise, according to Salud America! research reviews. Harmful chemicals in food and food containers also play a role.

These children also lack adequate healthcare, in which they are less likely to seek care and treatment. Transportation and parents taking time off of work is also a challenge.

Kehm went on to tell NPR that research is simply not enough.

“We need to figure out specific things we can do to address these disparities. There are things we can do now that don’t require money to pour into pharmaceutical development — things that are manageable and can actually make a difference now, today.”

Part of that effort means a more diverse healthcare workforce, experts say.

Latinos are sorely underrepresented in clinical research and the healthcare workforce, said Dr. Eliseo Perez-Stable, director of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities.

That’s why a program like Éxito! is so important.

Éxito!, led by Salud America! director Dr. Amelie G. Ramirez of UT Health San Antonio and funded by the National Cancer Institute, recruits 25 Latino students and health professionals annually for a culturally tailored curriculum to promote pursuit of a doctoral degree and cancer research career. The program also offers internships and ongoing support.

“Éxito! has proven a strong model pipeline program that equips Latinos for applying to and thriving in doctoral programs, with added potential to boost the pool of cancer health disparity researchers,” said Dr. Amelie G. Ramirez, director of both Éxito! and Salud America! at UT Health San Antonio.

By The Numbers

142

Percent

Expected rise in Latino cancer cases in coming years